A Decades-Long Legal Battle in Oklahoma Ends in Disappointment

A decades-long struggle for justice reached its conclusion on Wednesday when the Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit filed by the last two known survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre.

The plaintiffs, Lessie Benningfield Randle and Viola Fletcher, both centenarians, sought restitution for the devastation of their community, Greenwood.

The Lawsuit's Basis

The lawsuit was based on Oklahoma’s public nuisance law. It argued that the 1921 massacre’s effects persist today, contributing to Tulsa’s racial and economic divide.

Source: Freepik

However, the Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling, stating that while the grievances were legitimate, they did not fall under the public nuisance statute.

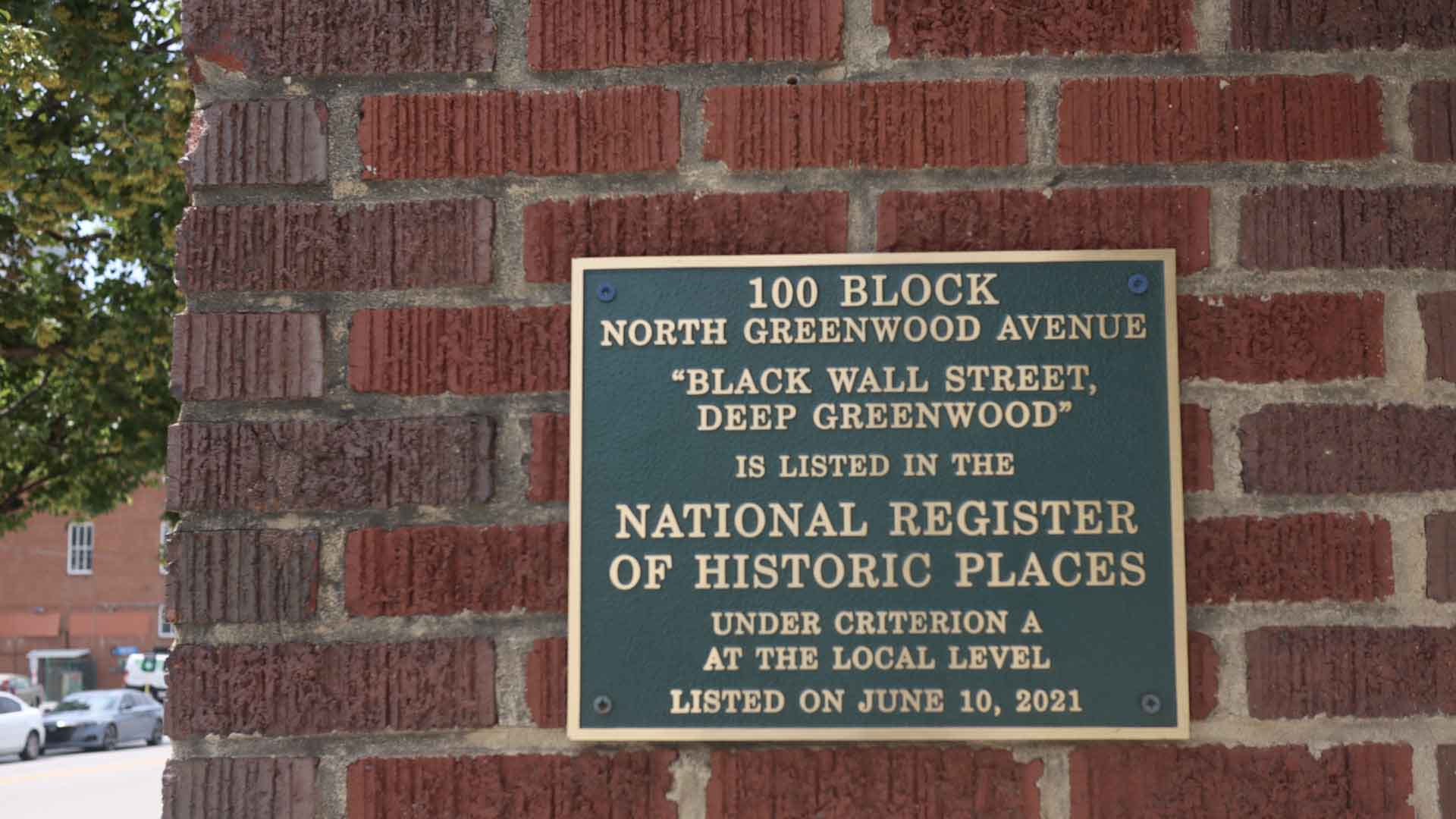

The Greenwood Community

Before the massacre, Greenwood was a thriving Black district in Tulsa, home to more than 10,000 Black Americans.

Source: NevinThompson/Wikipedia

Known as “Black Wall Street,” it was one of the most affluent Black communities in the country, showcasing Black entrepreneurship and prosperity.

The Inciting Incident

The destruction began on May 31, 1921, when Dick Rowland, a Black teenager, was accused of assaulting a white girl, Sarah Page.

Source: Tingey Injury Law Firm/Unsplash

The accusation, though unsubstantiated, was enough to ignite racial tensions and lead to devastating violence against the Black community.

Inflammatory Headlines

The white-owned Tulsa Tribune published incendiary headlines, calling for violent action against Rowland and the Black community.

Source: AbsolutVision/Unsplash

These headlines played a significant role in inciting the white mob that would eventually descend on Greenwood.

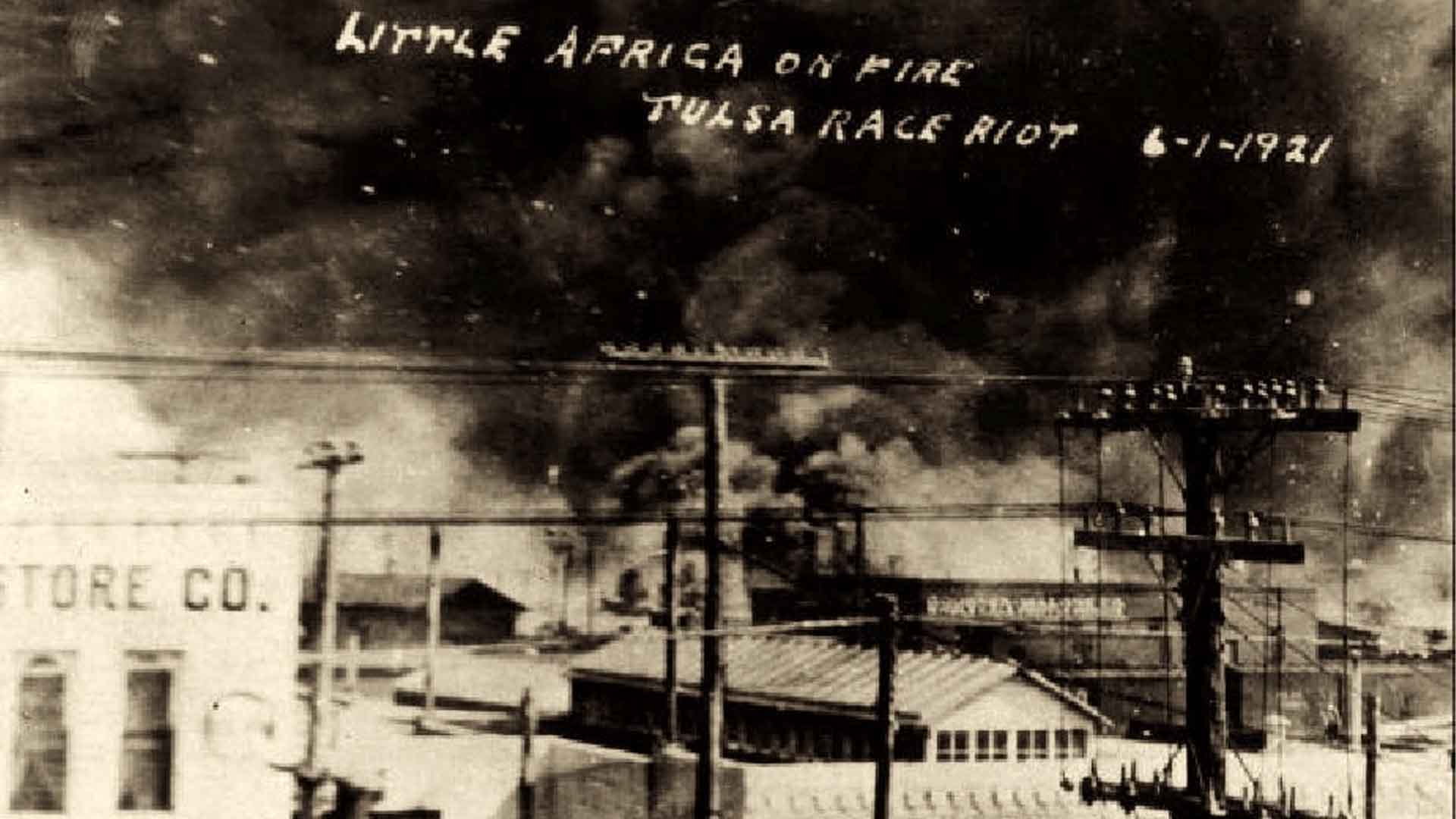

The Massacre Unfolds

The violence escalated quickly, with white mobs attacking Greenwood.

Source: American National Red Cross/Library of Congress/Reuters

White pilots flew over the neighborhood, dropping dynamite from airplanes, marking one of the first aerial bombings in U.S. history. The community was completely devastated in a matter of hours.

The Immediate Aftermath

The massacre resulted in the deaths of an estimated 100 to 300 Black individuals and the destruction of over 1,200 homes, businesses, and institutions.

Source: RDNE Stock Project/Pexels

The aftermath also saw mass arrests of Black residents, who were only released with white sponsors.

Hurdles in Rebuilding

Attempts to rebuild Greenwood were met with resistance from local officials. They amended building codes to require expensive fire-proof materials, making reconstruction prohibitively costly for many residents.

Source: McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa/Wikipedia

These actions further entrenched the damage done by the massacre.

Survivors' Memories

On the 100th anniversary of the massacre, survivor Viola Fletcher recalled the chaos and fear of that night.

Source: NevinThompson/Wikipedia

She remembered “seeing airplanes flying, and a messenger going through the neighborhood telling all the Black people to leave town,” highlighting the terror inflicted on the community.

Court's Rationale

The Supreme Court’s decision emphasized the challenge of holding current actors accountable for historical wrongdoings.

Source: Freepik

They argued that expanding public nuisance liability to historical injustices could create “unlimited and unprincipled” liability, which the court was not willing to endorse.

Broader Implications

The dismissal of the lawsuit highlights the broader difficulties in addressing historical injustices through contemporary legal frameworks.

Source: Tingey Injury Law Firm/Unsplash

It showcases a prime example of the ongoing struggle for reparations and justice for communities impacted by past atrocities.

The Fight for Justice Ends

The end of this legal battle is a significant moment in the ongoing fight for justice for the Tulsa race massacre survivors.

Source: Zachary Caraway/Pexels

While their grievances were technically acknowledged, the legal path for reparations remains unresolved, reflecting the broader challenges of addressing historical injustices today.