Amateur Archaeologist Deciphers 20,000-Year-Old Rock Writing

An amateur archaeologist from Britain has made a groundbreaking discovery that could potentially rewrite history. His research suggests that cave art throughout Europe may contain a previously undeciphered primitive writing system used by ancient hunter-gatherers living on the continent during the last ice age.

Working alongside Durham University and University College London professors, Ben Bacon found evidence to suggest that cave art markings dating back over 20,000 years may represent an ancient lunar calendar.

The Unknown Markings

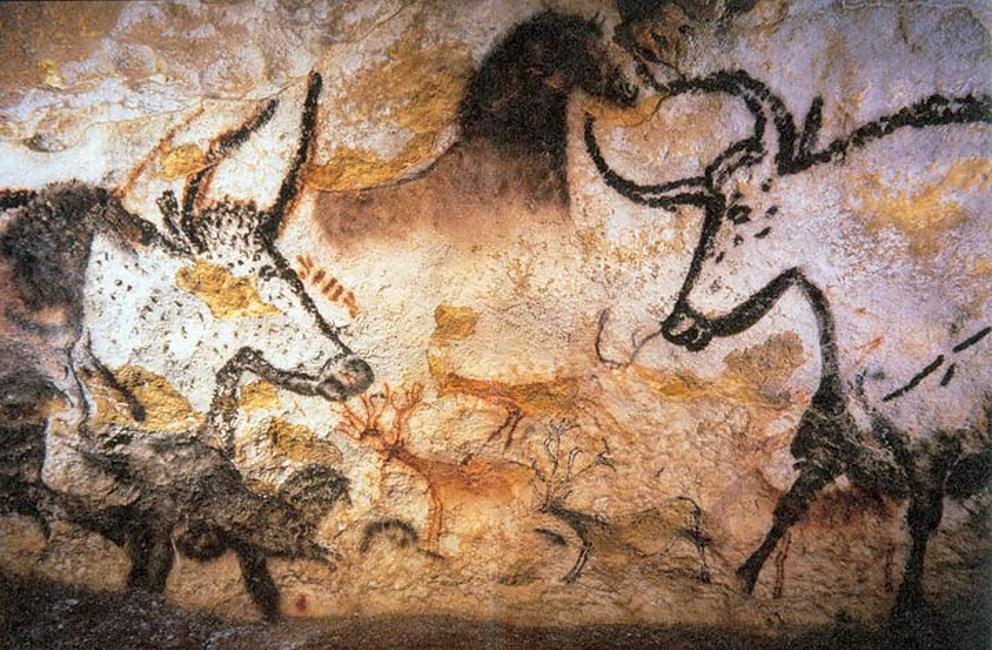

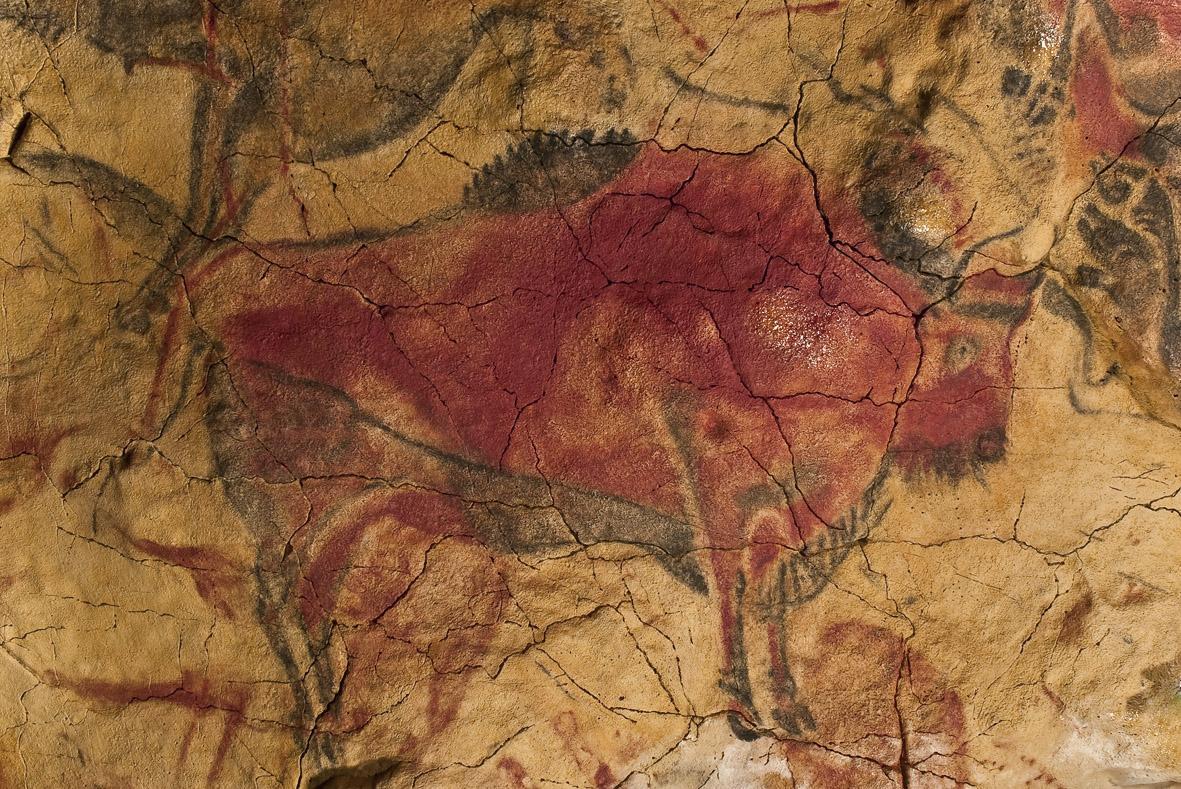

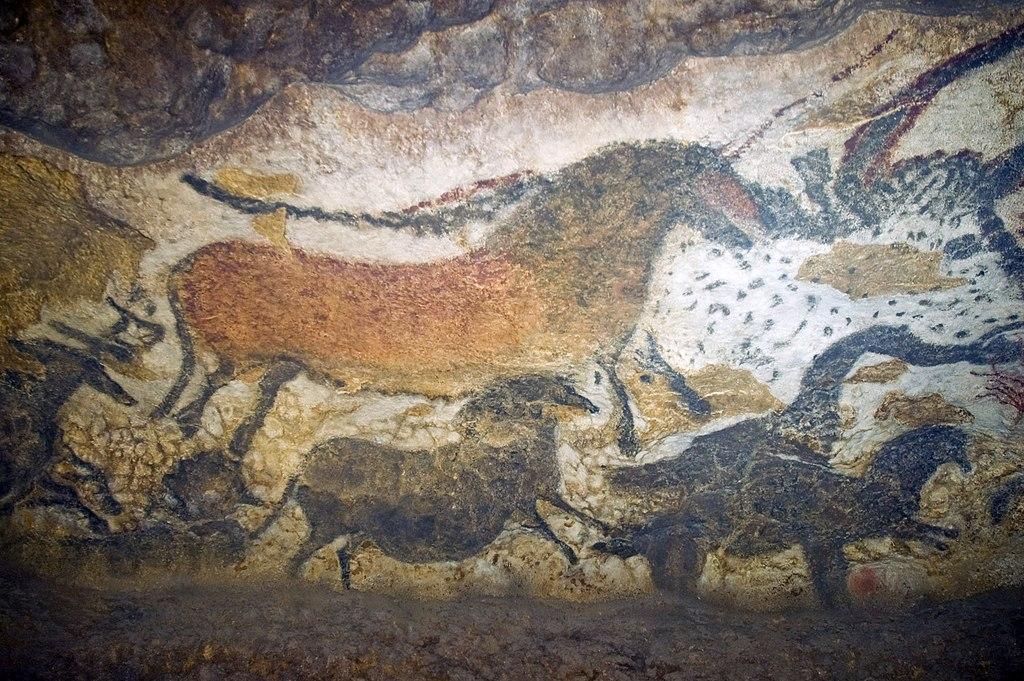

Animal paintings and engravings cover the caves in Lascaux and Chauvet in France and Altamira in Spain. Researchers discovered these pieces of primitive art 150 years ago, leaving them puzzled about one thing.

Source: Andrea Piacquadio/Pexels

Between the depictions of animals, enigmatic abstract markings and geometric signs often appear alongside them. However, researchers needed clarification on what these markings meant.

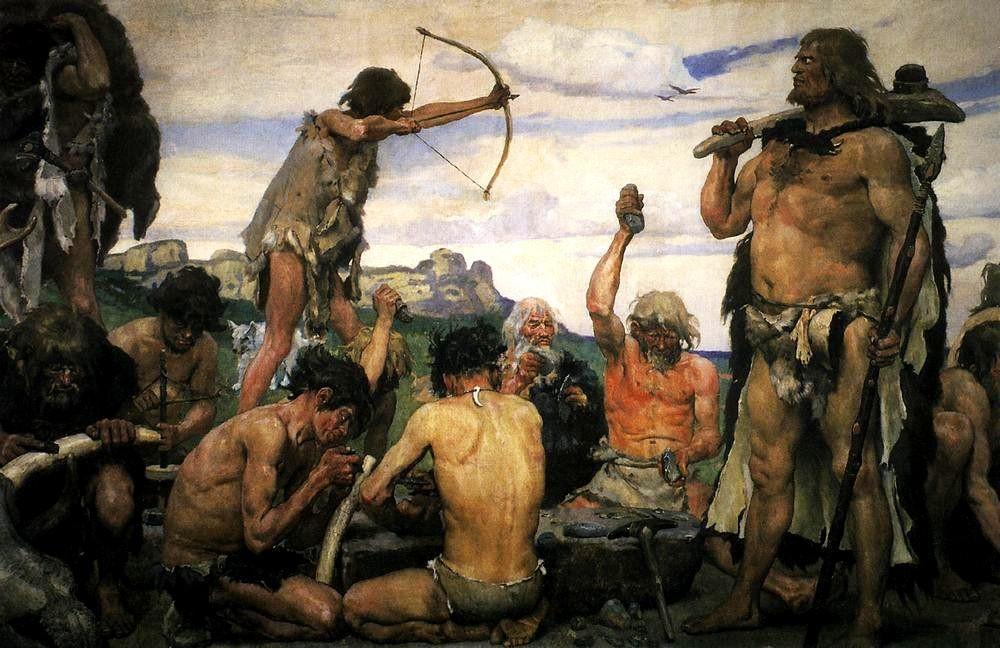

Paleolithic Cave Art Europe

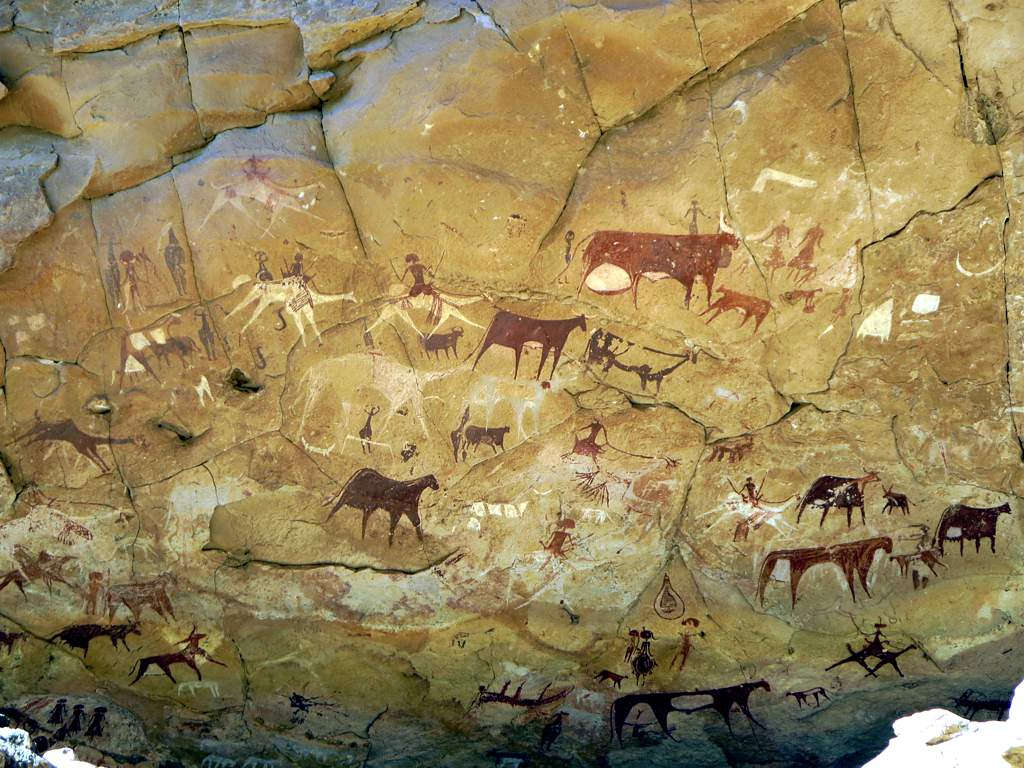

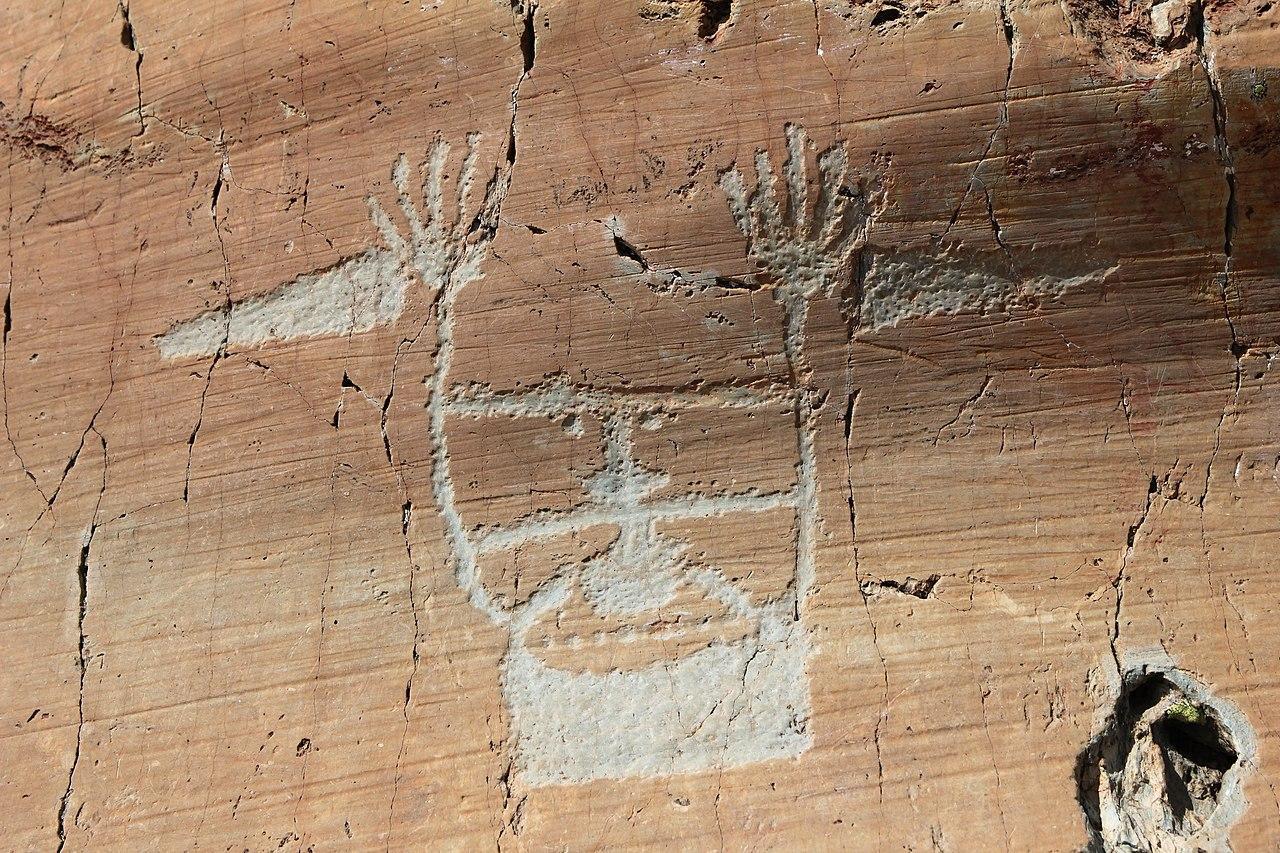

Hundreds of cave paintings have been found throughout Europe, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic, the oldest of which go back around 40,000 years.

Source: Wikimedia

Created by some ancient homo-sapiens on the continent, the artwork consists of figures and animals, which are sometimes accompanied by signs that have yet to be deciphered. Frequent designs include vertical lines, dots, and Y-shaped slashes, many of which appear in groups.

Interest in Europe’s Ancient Cave Art

Cave art found throughout Europe has long fascinated archaeologists and historians from the continent and beyond.

Source: Wikimedia

Despite being studied extensively, researchers have struggled to develop a meaning behind the strange symbols, as no one was able to decode the peculiar signs successfully.

Amateur Archaeologist Tries to Decode the Cave Art

Ben Bacon, who works in the furniture conservation business, has long been fascinated by the ancient art that covers caves across Europe and has taken it upon himself to get to the bottom of the mystery.

Source: Wikimedia

According to the amateur archaeologist who has extensively studied many frescos, including examples in Altamira, Spain, and Lascaux, France, the depictions may go beyond artistic expression and may actually be a primitive form of writing.

Young Researcher Attempts to Decipher Symbols

Bacon has spent a considerable amount of time attempting to decipher the proto-writing system, which, if proven true, would predate all other examples by at least 10,000 years.

Source: Freepik

According to Bacon’s initial theory, the dots, lines, and Y-shaped slashes may represent a writing system used to measure time, which was quite possibly related to animal reproductive cycles, per The Guardian.

Secrets in the Best-Known Cave Painting

One of the best-known and biggest cave paintings is an 18-foot-wide image of an extinct wild ox or aurochs, that is galloping across the great Hall at Lascaux. Bacon noticed four small dots painted across the animal’s back.

Source: David Stanley/Wikimedia Commons

Upon closer inspection, he found that the markings correspond to specific numbers, recorded by rows of dots or lines.

The Advantage Bacon Had

Another advantage Bacon had was the amount of examples available to him. “Another advantage is we accumulated 700 examples of these, and across large databases, patterns demonstrate themselves.”

Source: Wikimedia

They pulled many examples from databases at local libraries, the university library, and sources Bacon contacted.

Researcher Contacts Professors for Credibility

The amateur archaeologist collected reproductions of various frescos from across Europe to include in his study. Later, he collaborated with professors at University College London and Durham University, significantly bolstering his research’s credibility.

Source: Wikimedia

He was encouraged by the professors to pursue the theory despite feeling like “a person off the street.”

Bacon Publishes a Paper Alongside Professors

After collecting enough data, Bacon later collaborated with a team that included two professors from Durham University and published a paper in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

Source: Freepik

Regarding his decision to join the project, Professor Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist at Durham University, said he was “glad he took it seriously.”

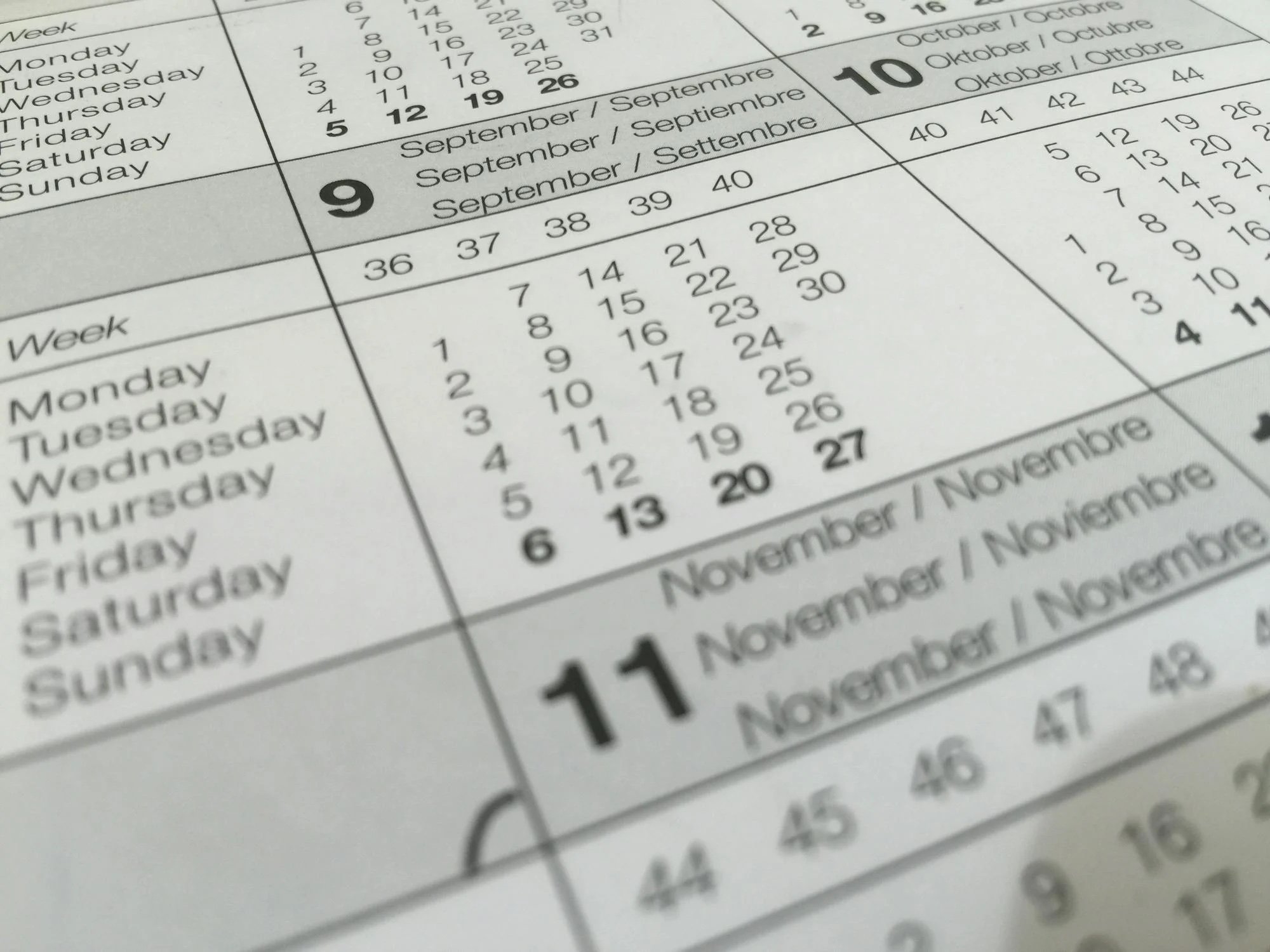

The Use of a Calendar in Paleolithic Europe

Pettitt explained that the study’s results suggest that ancient hunter-gatherers created a calendrical system that allowed them to track the passing of time using symbols.

Source: Wikimedia

“The results show that ice age hunter-gatherers were the first to use a systemic calendar and marks to record information about major ecological events within that calendar,” he said.

Ancient Homo-Sapiens Tracked the Birth of Animals

The researchers explained that they began by using the birth cycles of animals similar to those depicted in cave art as a reference point.

Source: Wikimedia

This allowed them to theorize that the symbols associated with animal species present in Europe during the ice age were a record of their mating behavior. According to their study, the mysterious “Y” symbol meant “giving birth.”

A Lasting Legacy

Professor Pettitt explained that the study showcases the legacy left behind by the prehistoric cave artists.

Source: Wikimedia

“We’re able to show that these people – who left a legacy of spectacular art in the caves of Lascaux and Altamira – also left a record of early timekeeping that would eventually become commonplace among our species,” he said.

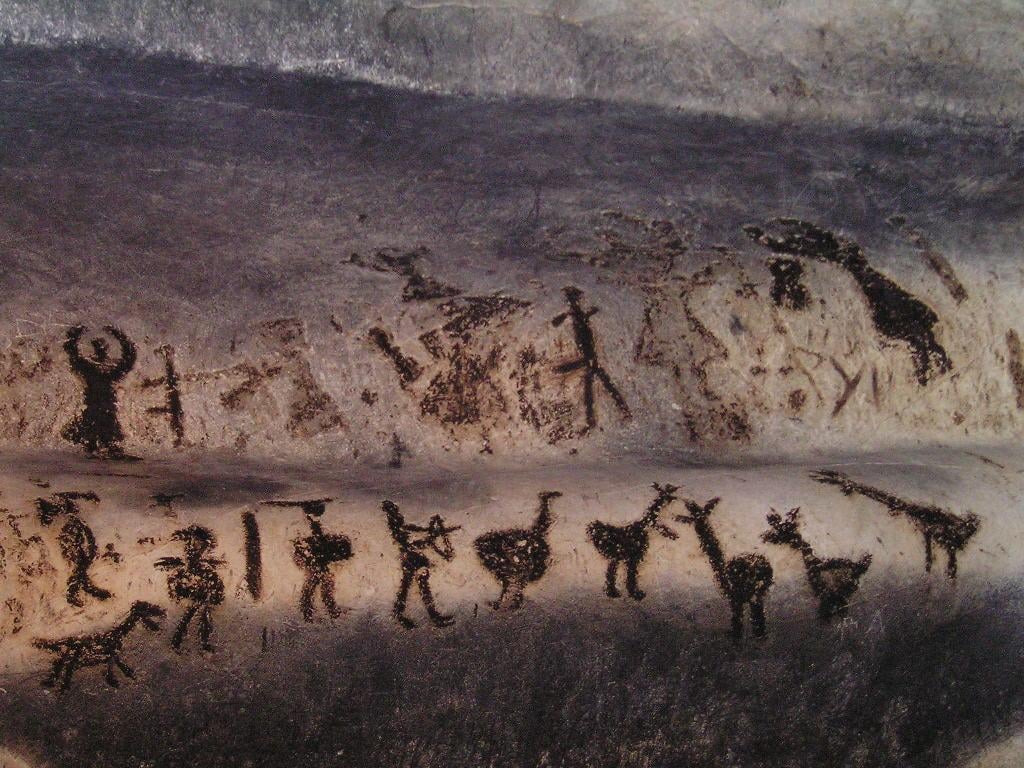

Proto-Writing System

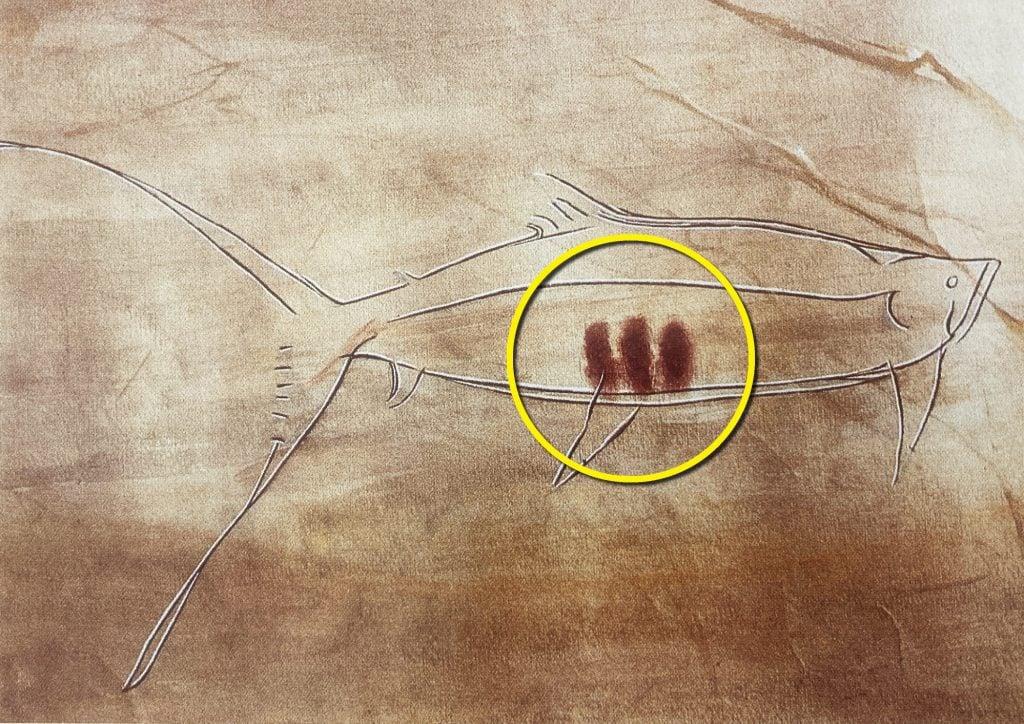

The researchers suggest the markings record numerical information as opposed to speech.

Source: Berenguer, M., 1994

In this sense, it is not considered a traditional form of “writing” that evolved in Mesopotamia around 3,500 BCE. Instead, it has been classified as a proto-writing system.

The First Calendar

The result of the study suggests that the Ice Age hunter-gatherers were the first to have a systematic calendar and record information about major ecological events in that calendar.

Source: Pixabay/Pexels

Kentridge added: “The implications are that Ice Age hunter-gatherers didn’t simply live in their present, but recorded memories of the time when past events had occurred and used these to anticipate when similar events would occur in the future, an ability that memory researchers call mental time-travel.”

Extremely Simple Numbers

While this writing is extremely simple, similar to Roman numerals, the system was keeping track of time.

Source: Anna Shvets/Pexels

Bacon says that the hunter-gatherers did not need numbers as we currently do, so the “only logical reason that they would exist would be to track time,” he said to NPR.

Not the First to Present the Theory

Bacon notes that he was not the first one to put this theory forward. “And this is an idea that had been put forward in the ’70s by a man called Marshak, but he wasn’t able to demonstrate the system because he thought that these individual lines were days,” he said.

Source: Wikimedia

But Bacon and Pettitt were able to look at how the system correlates with the animals painted with the markings.

The Need for Calendars

“What we did is we said they’re months because a hunter-gatherer doesn’t need to know what day a reindeer migrates,” Bacon said.

Source: Eric Rothermel

Bacon continued: “They need to know what month the reindeer migrates. And once you use these months units, this whole system responds very, very well to that.”

The Key to Understanding

Bacon believes that the key to understanding this primitive writing was looking at the entire picture. “I think the key was we didn’t dismiss the animal. We processed the animal. There were three fish.”

Source: Freepik

Bacon continues: “And other people would concentrate on the fish and the color of the fish and the form of the fish and all the rest of it. And we just said, no. It’s a fish, and it’s a three. The third is the importance of it. So if you start focusing on the number, it becomes a lot easier to do.”

Making Winters Bearable

Hunter-gatherers were using numbers as a way to further immerse themselves in their environment. To help them further understand their environment and up their chances for survival, they tracked and recorded on the walls of caves.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Bacon also suggests that tracking the animals throughout the spring, summer, and fall makes the brutal winters more bearable.

We Don’t Need the Numbers

While the primitive language can reveal something about past civilizations, Bacon emphasizes that there is no connection between modern humans and hunter-gatherers.

Source: katemangostar/Freepik

New evidence is proving that primitive humans were much more clever than we once believed, despite their culture being far simpler than that of modern-day humans.

Connecting Us to the Past

Bacon does note that despite the differences between us and hunter-gatherers, this new evidence could open up a new connection between us and our ancestors.

Source: Wikimedia

“We think there’s a difference between us and them. And we’re saying we cannot distinguish the difference between us intellectually or cognitively. We are the same as they are,” Bacon said.

Similarities Between Ancient Homo-Sapiens and Modern Humans

Bacon finished by saying, “As we probe deeper into their world, what we are discovering is that these ancient ancestors are a lot more like us than we had previously thought.”

Source: Wikimedia

He added, “What we are hoping, and the initial work is promising, is that unlocking more parts of the proto-writing system will allow us to gain an understanding of what information our ancestors valued.”

A Surreal Experience

Bacon said it was a “surreal” experience to “slowly work out what people 20,000 years ago were saying but the hours of hard work were certainly worth it,” (via BBC) and encourages others to utilize the resources available to them.

Source: Freepik

“Using information and imagery of cave art available via the British Library and on the internet, I amassed as much data as possible and began looking for repeat patterns,” Bacon said.