Chemical Analysis of Natural CO₂ Rise Over The Last 50,000 Years Reveals Today’s Current Rate Is 10 Times Quicker

The current rate of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) increase is 10 times faster than at any other point in the past 50,000 years.

This discovery comes after researchers studied the chemicals in ancient Antarctic ice, providing crucial insights into the abrupt climate change periods in Earth’s history.

The Study

The study, led by Kathleen Wendt, an assistant professor at Oregon State University’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, aimed to provide an important understanding of the Earth’s history of climate change.

Source: Katherine Stelling, Oregon State University

The study also aims to offer new insights into the potential impacts of modern-day climate change.

The Rise of CO2

The findings, published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” emphasize the unprecedented nature of the current CO2 rise in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Source: Melissa Bradley/Unsplash

“Our research identified the fastest rates of past natural CO2 rise ever observed, and the rate occurring today, largely driven by human emissions, is 10 times higher,” Wendt said.

CO2 Is Naturally Occurring

CO2 is a greenhouse gas that occurs naturally in the atmosphere, contributing to the warming of the climate due to the greenhouse effect.

Source: Freepik

In the past, CO2 levels fluctuated due to ice age cycles and other natural causes. However, human emissions since the industrial period have significantly contributed to the rise in CO2 levels.

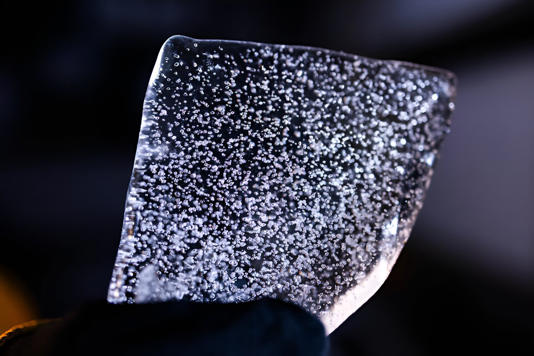

Measuring the CO2 in Ancient Ice

To analyze past climate conditions, scientists and researchers behind the study drill cores up to 2 miles deep into the Antarctic ice, which has built up over hundreds of thousands of years.

Source: Katherine Stelling, Oregon State University

The ice contains ancient atmospheric gases trapped inside air bubbles.

Identifying Patterns

Using samples collected from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Divide ice core, Wendt and her team investigated what the climate might have looked like during past periods.

Source: Melissa Bradley/Unsplash

The team observed patterns that demonstrated how carbon dioxide levels changed alongside the North Atlantic cold intervals known as Heinrich Events, which accompany abrupt climate shifts.

The Power of Heinrich Events

“These Heinrich Events are truly remarkable,” said Christo Buizert, an associate professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and co-author of the study. “We think they are caused by a dramatic collapse of the North American ice sheet.

Source: Emiliano Arano/Pexels

The co-author continues: “This sets into motion a chain reaction that involves changes to the tropical monsoons, the Southern hemisphere westerly winds, and these large burps of CO2 coming out of the oceans.”

Uncovering 10,000 Years of Climate Change

Scientists use samples of the collected ice to analyze trace chemicals and build records of past climates.

Source: 66 north/Unsplash

Previous research has suggested several periods during the last ice age, which ended about 10,000 years ago, when carbon dioxide levels appeared to jump much higher than average.

The Holes in the Research

However, those measurements lacked the necessary detail to fully understand the nature of these rapid changes. Scientists’ abilities to comprehend the data provided to them have left much information about the Earth’s climate history to be a mystery.

Source: Freepik

“You probably wouldn’t expect to see that in the dead of the last ice age,” she said. “But our interest was piqued, and we wanted to go back to those periods and conduct measurements at greater detail to find out what was happening.”

The Rapid Change

During the largest of the natural rises, CO2 levels increased by about 14 parts per million over 55 years.

Source: Cassie Matias/Unsplash

This type of jump occurred about once every 7,000 years or so, according to the study. Today, similar increases occur about every 5 to 6 years.

CO2 and Its Role in Climate Change

The evidence found in this study suggests that past periods of natural CO2 level rises play an important role in the circulation of the deep ocean.

Source: Andrzej Kryszpiniuk/Unsplash

Other research has indicated that these westerlies are likely to strengthen over the next 100 years due to climate change, leading to the Southern Ocean’s inability to absorb human-generated carbon dioxide.

Further Research Is Needed

Wendt emphasized the importance of this finding: “We rely on the Southern Ocean to take up part of the carbon dioxide we emit, but rapidly increasing southerly winds weaken its ability to do so.”

Source: Lukas/Pexels

Studies like this underscore the need to continue research and action to mitigate the effects of human-induced climate change.