Experts Finally Uncover What Ended the Aztecs

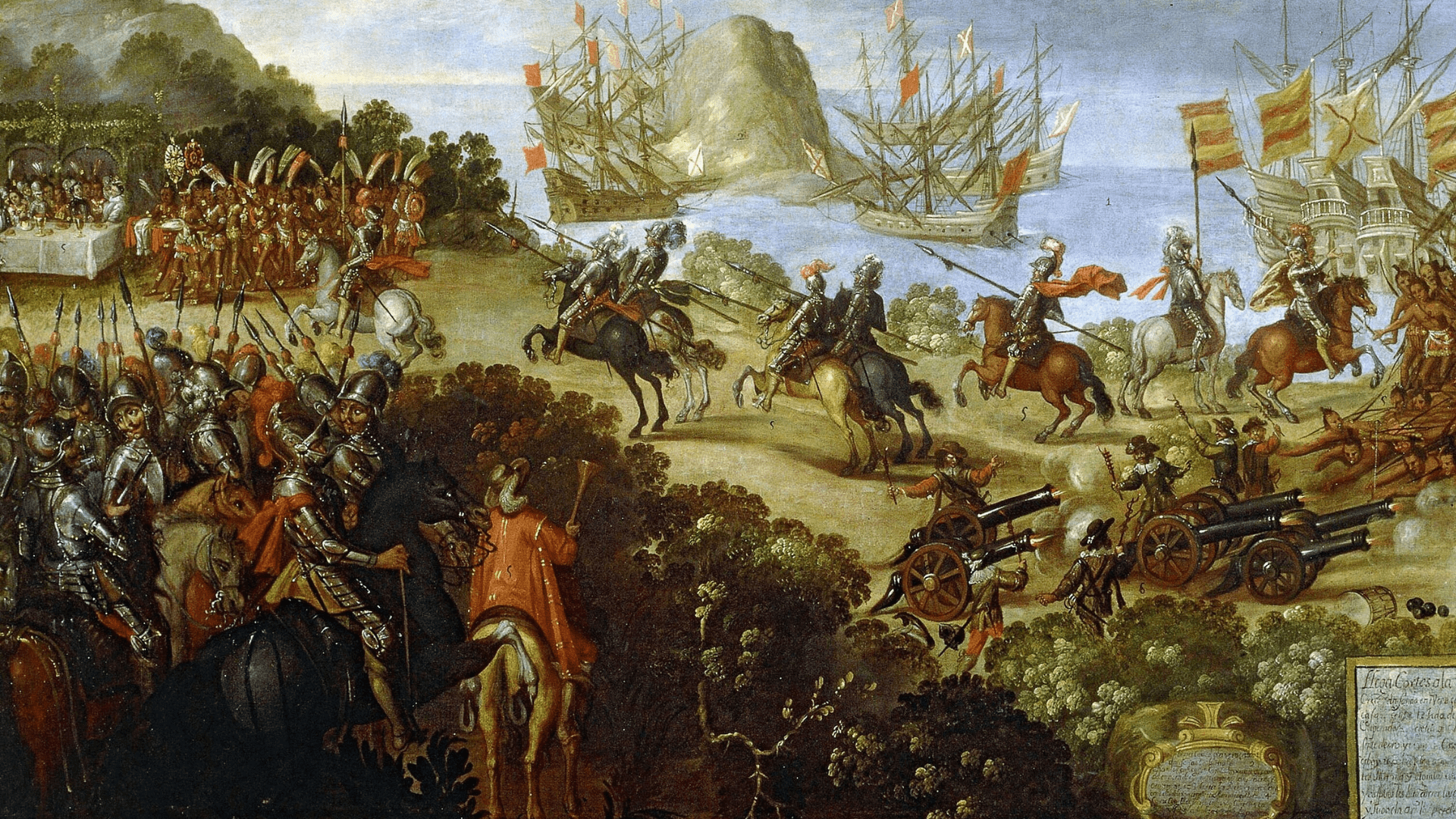

The official last stand of the Aztec Empire occurred in 1521, after a three-month siege led by Hernán Cortés. Cortés commanded a coalition of Spanish forces and native Tlaxcalan warriors who eventually captured Emperor Cuauhtémoc and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

Widespread disease from smallpox (brought by the Spanish), famine, and internal strife had already weakened the Aztecs. They no longer had the numbers or the strength to withstand the persistent Spanish onslaught. The siege of Tenochtitlan is the conclusive and pivotal battle that ultimately ended the Aztec Empire. Still, the Aztec civilization held on in reasonable numbers for some time longer under their European rulers.

Mysterious Illness Sweeps Through the Aztec Population

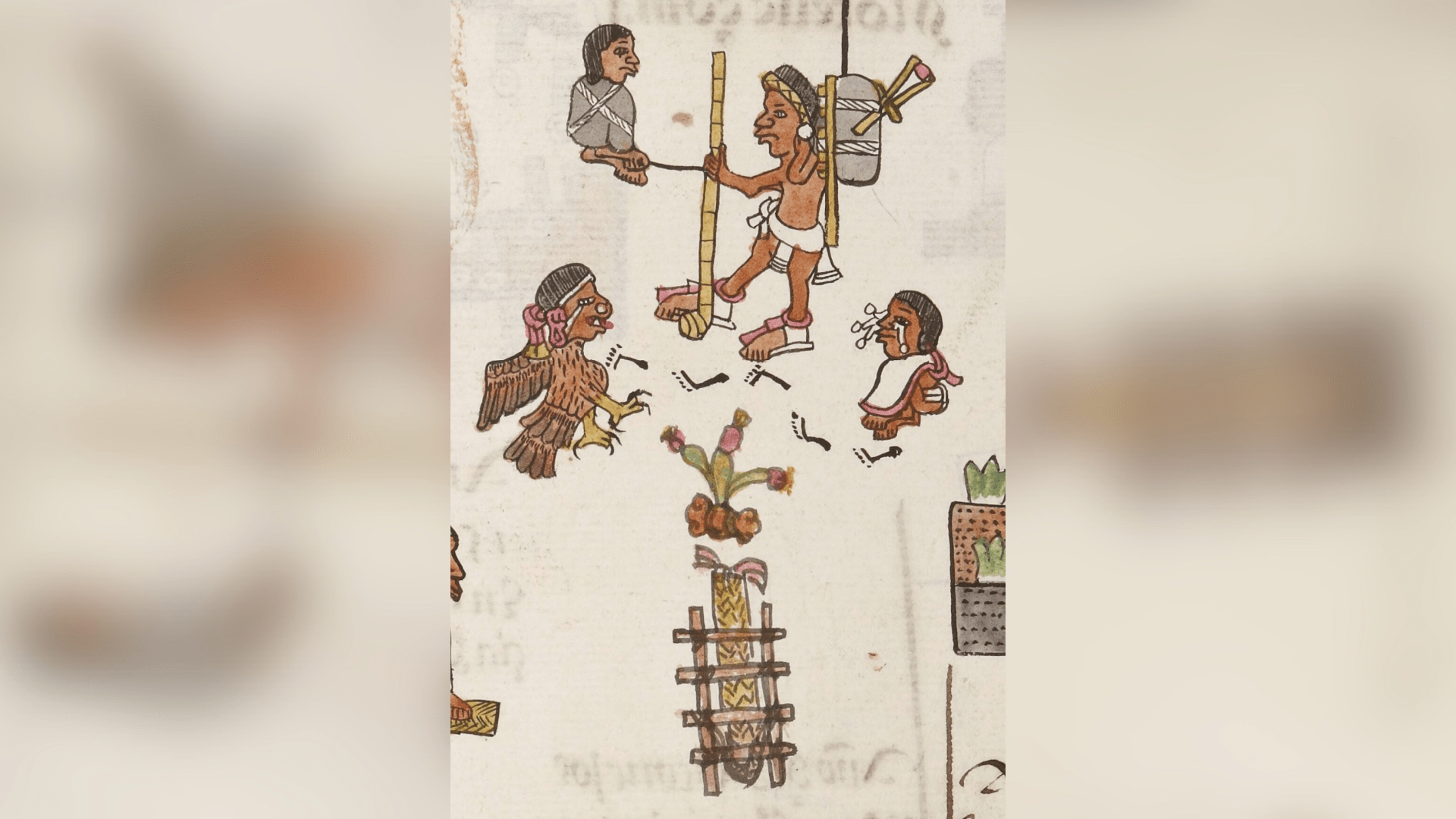

However, in 1545, the Aztec civilization faced an almost complete collapse. A mysterious illness known as “cocoliztli” (“pestilence” in Aztec Nahuatl language) swept through the population, causing high fevers, headaches, bleeding from the eyes, mouth, and nose, ultimately leading to death.

SkybirdForever/Wikimedia Commons

By 1550, this calamity had claimed the lives of approximately 15 million people, representing 80 percent of the Aztec population. The puzzle of this catastrophic event has intrigued scientists for many years, as they’ve sought to uncover the origins and mechanisms of this incredibly deadly outbreak in Mexico.

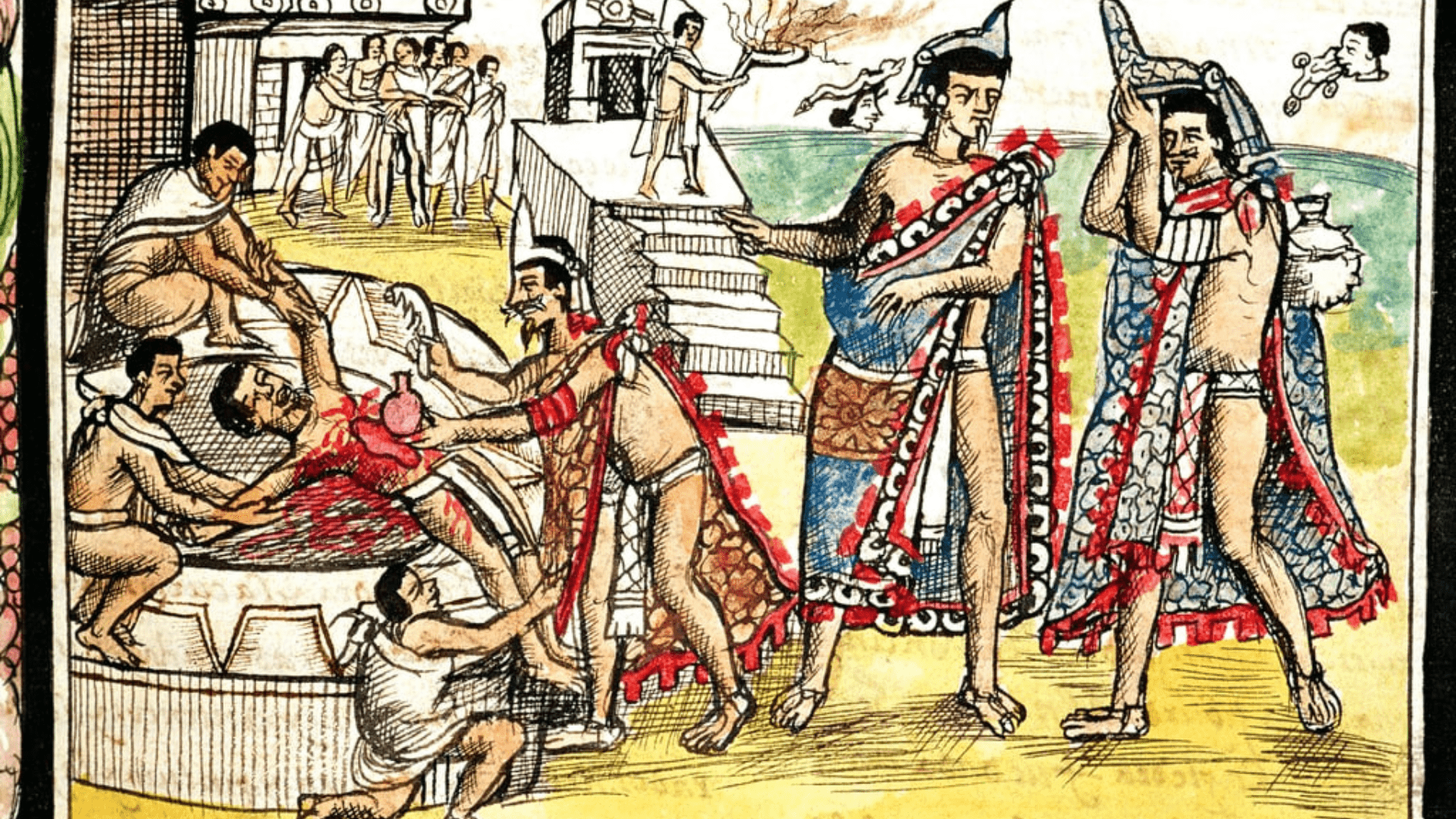

Scholars Have Long Thought Cocoliztli was Blood-Borne

Historians and archaeologists have long suspected a blood-borne illness as the cause of cocoliztli. Both Spanish and indigenous artistic depictions depict victims with nosebleeds and coughing up blood. However, finding direct physical evidence has proven challenging.

Diego Durán/Wikimedia Commons

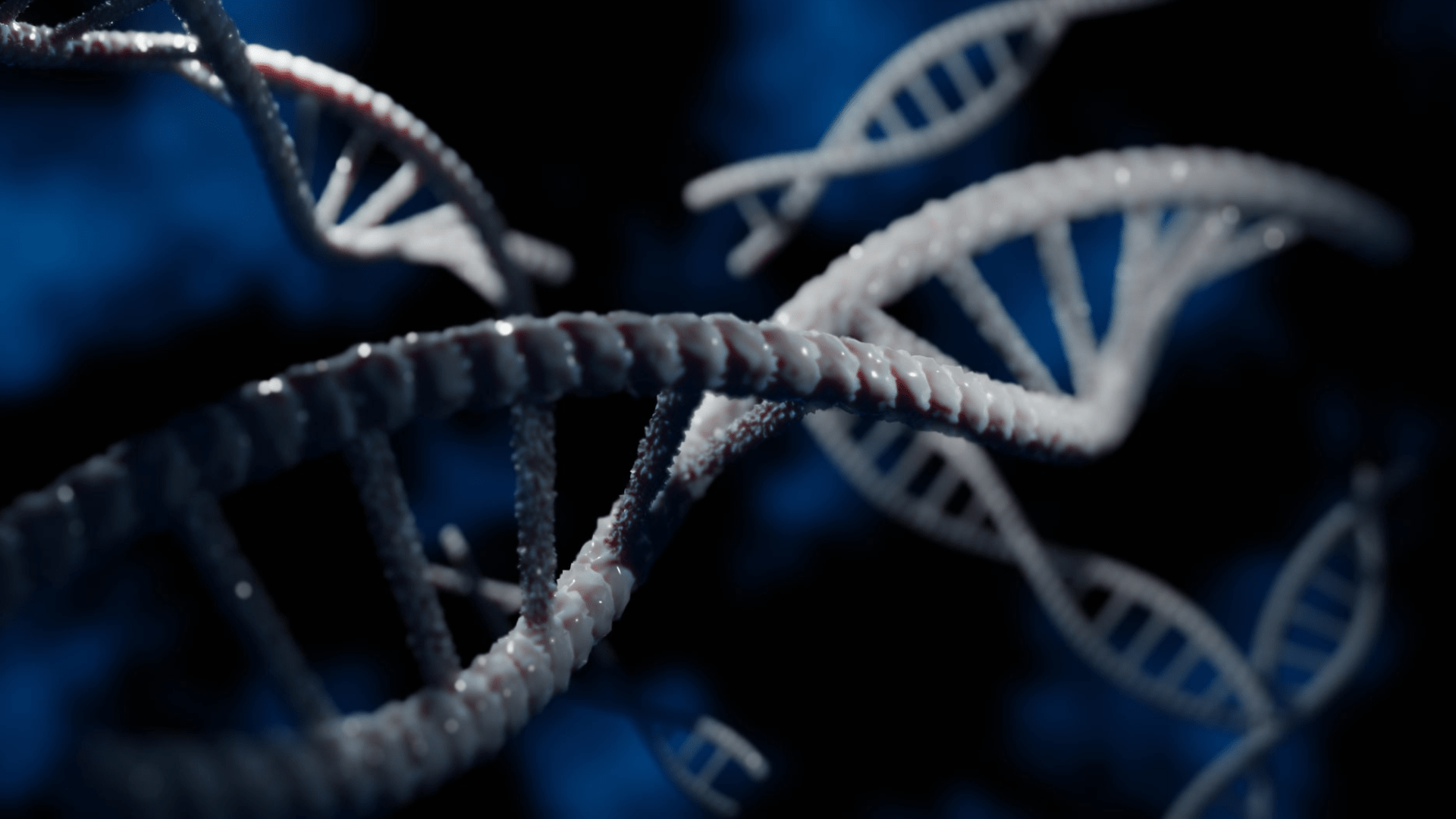

According to researcher Åshild Vågene, diseases like cocoliztli don’t leave visible clues on skeletons, making identification difficult. Alexander Herbig, a coworker of Vågene’s, highlights the significance of avoiding assumptions in their research. Instead of hypothesizing about various pathogens, researchers could test DNA against a comprehensive database.

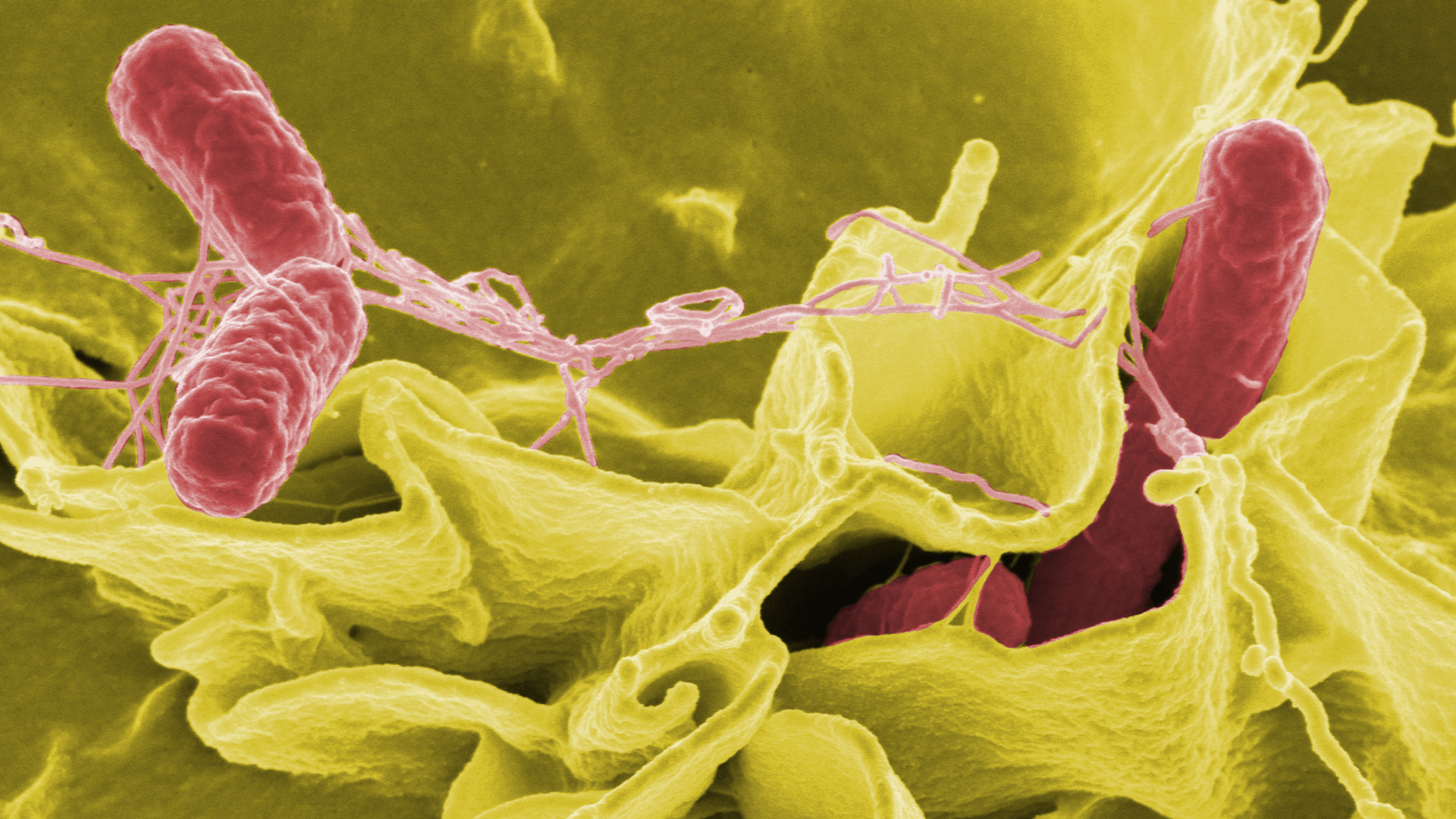

Researchers Discover the Origin of “Cocoliztli”

This discovery was a groundbreaking revelation, as the researchers may have finally unraveled a five-century mystery.

NIAID/Wikimedia Commons

Through an exhaustive analysis of DNA extracted from the teeth of ancient victims, scientists propose that the probable cause of the pestilence was a typhoid-like “enteric fever” induced by Salmonella enterica, specifically the subspecies Paratyphi C.

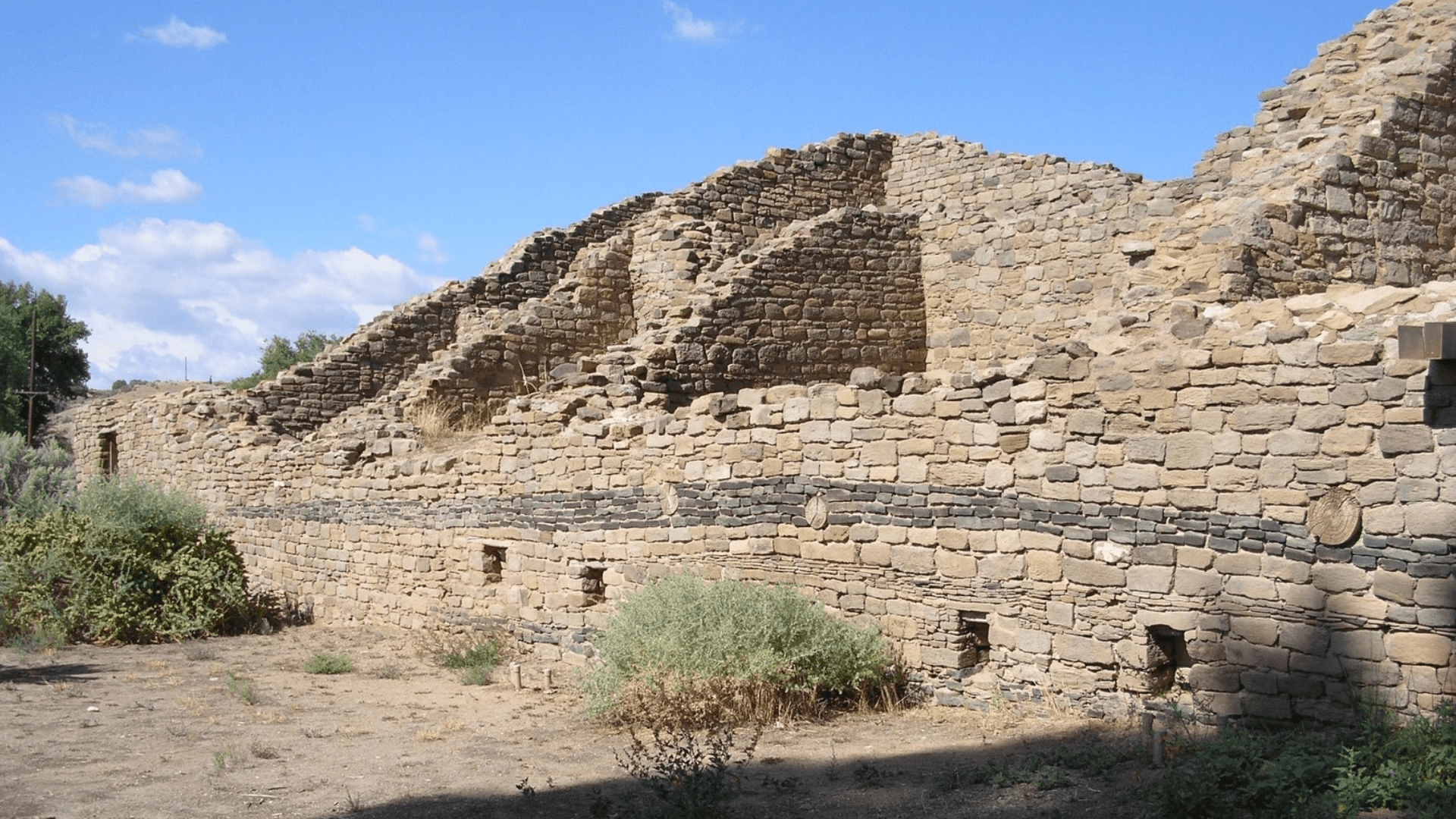

Scientists Find Salmonella enterica in Oaxaca Cemetery

Research employed an advanced metagenomic analysis tool, MALT, designed for the detection of ancient pathogen DNA. With this equipment, scientists successfully identified the presence of Salmonella enterica in individuals interred at an epidemic cemetery in Teposcolula-Yucundaa, Oaxaca, Southern Mexico.

Bernard Gagnon/Wikimedia Commons

This burial site has been archaeologically and historically associated with the epidemic that transpired between 1545 and 1550 CE, impacting significant regions of Mexico.

What is Paratyphi C.?

Paratyphi C. is a bacterial pathogen associated with enteric fever, typically transmitted through contaminated food or water.

Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons

This bacterium shares similarities with modern-day Salmonella strains, often linked to raw eggs, although it rarely causes infections in humans today. The study, utilizing ancient DNA from 24 skeletons discovered in a cocoliztli cemetery, pinpointed Paratyphi C. as the predominant germ, although the researchers acknowledged the potential existence of other undetectable or unknown pathogens.

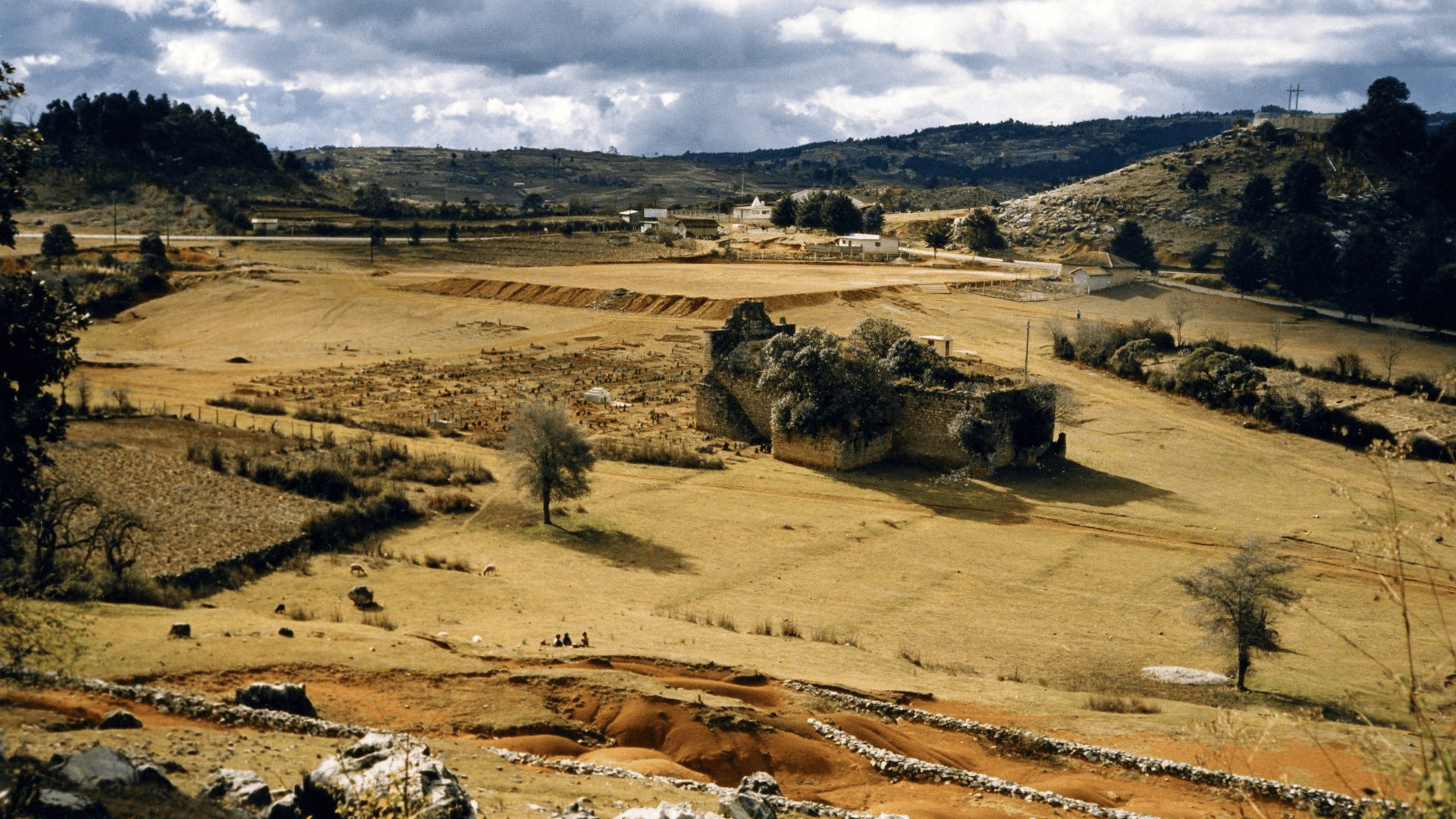

Scientists Attribute Paratyphi C. to European Colonizers

The findings, documented in the scientific journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, not only shed light on the cause of the pestilence but also attribute its origin to European colonizers.

Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons

The prevailing theory suggests that animals carrying the Paratyphi C. pathogen accompanied settlers to Mexico.

Colonizers Possessed Immunity, Aztecs Did Not

These European colonizers had encountered the bacterium before and therefore possessed immune systems capable of handling the pathogen.

Meisterdrucke/Wikimedia Commons

However, the Aztecs, lacking any prior exposure to such diseases, succumbed to the devastating consequences.

Why Do Scientists Attribute Disease to Colonizers?

The researchers identified the same strain of salmonella in the DNA remains of a Norwegian woman who died in 1200.

Tim Tim (VD fr)/Wikimedia Commons

This implies that the specific strain potentially responsible for the Aztec deaths in the 16th century existed 300 years earlier, across the Atlantic. While it’s conceivable that the pathogen might have already been in Mexico, no conclusive evidence supporting this hypothesis has been discovered, according to Vågene.

Additional DNA Testing Necessary for Certainty

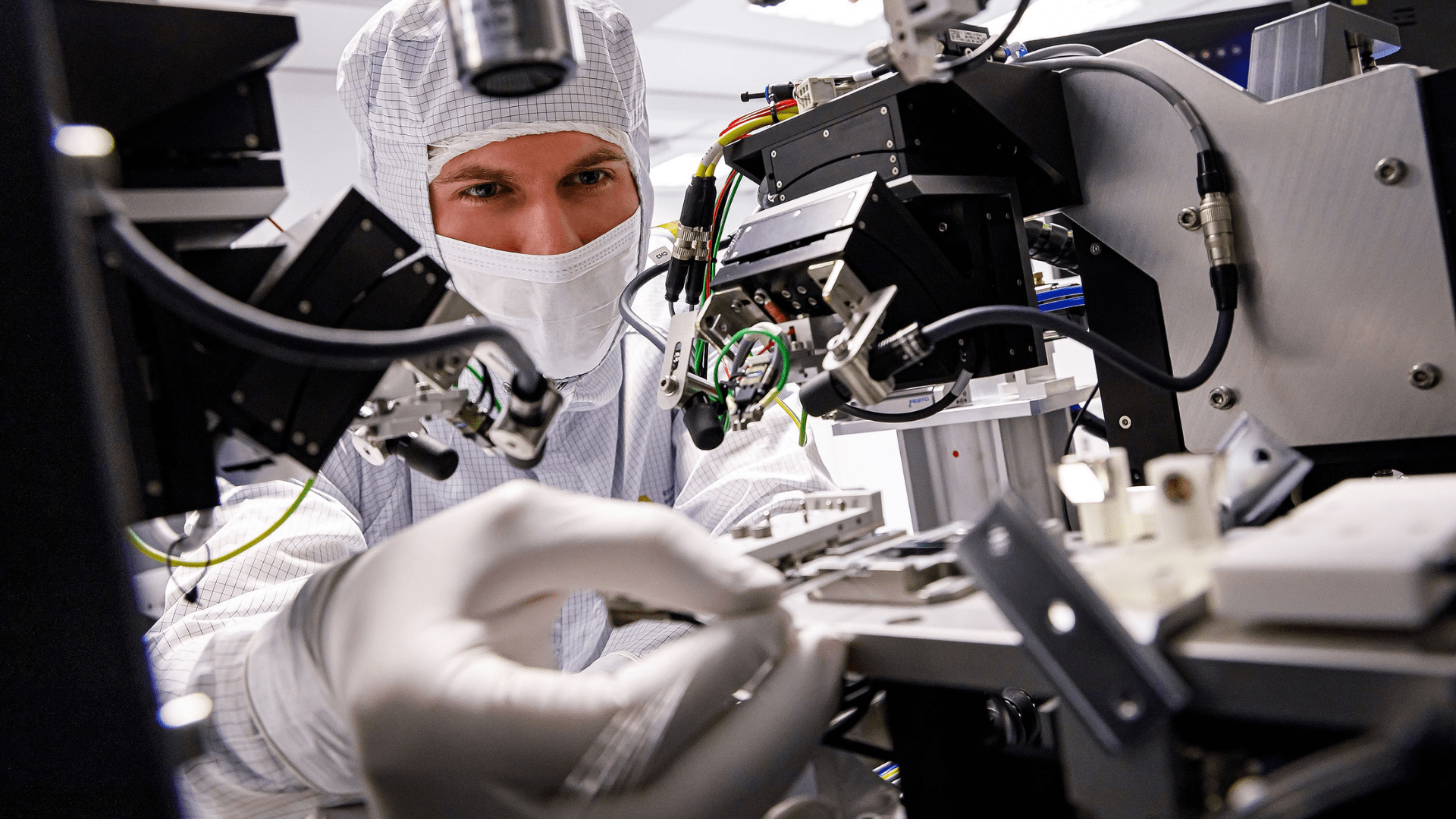

To definitively establish salmonella’s role in the historical outbreak in Mexico, researchers would need to conduct additional DNA testing from various sites.

Source: FMNLab/Wikimedia Commons

Caitlin Pepperrell, an infectious disease researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison not involved in the study, suggests the possibility of multiple agents contributing to the epidemic.

Multiple Agents Could Have Played a Role in the Epidemic

Factors related to colonialism, such as disruptions in food supplies, famine, population concentration changes, and relocations, could have played a role.

Bibliothèque nationale de France/Wikimedia Commons

Anne Stone from Arizona State University’s School of Evolution and Social Change, also not part of the study, says that while it’s challenging to be certain, the likelihood of the pathogen originating in Europe is high, given its novelty to the population and the severity of its impact.

Unintended European Impact on Indigenous Populations

While past speculations considered diseases like influenza, smallpox, and measles brought over from Europe, the study effectively dismisses these possibilities.

Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons

As we’ve seen, the focus is now on Paratyphi C. as the likely culprit. It seems reasonable to suggest at this time that Salmonella strain was carried by Spanish colonizers in Mexico. All of this works to show the impact of European contact on indigenous populations and the unintended consequences of cross-cultural interactions.