Native American Boys Died 130 Years Ago at a Boarding School, the Tribe Is Now Suing for the Remains

Just 150 years ago, it was common practice to remove young Native American boys from their homes and force them to travel thousands of miles away to attend government-run boarding schools.

Sadly, many of the young men died at the schools, and their families were never able to see their bodies, let alone bring them home to rest. Now, tribes around the country, including the Winnebago Tribe, are fighting for the government to release their ancestors’ remains so they can rest peacefully at home.

The Winnebago Tribe Filed a Lawsuit Against the Army

Leaders of the Winnebago Tribe from Nebraska have filed a lawsuit against the United States Army. The suit claims that they have not adhered to the federal law, which requires them to return deceased Native Americans to their ancestral lands.

Source: Winnebegotribe.com

The law to which they are referencing was put into place more than 30 years ago. However, the Winnebago Tribe is still waiting for the remains of two boys who died in the 1800s to be returned by the army.

Understanding NAGPRA

In order to understand the current lawsuit, it’s first essential to learn about the law in question. Known as NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act was established in 1990.

Source: National Park Service

According to NAGPRA, all federal agencies and institutions will receive federal funding for the “return of human remains and cultural objects unlawfully obtained from pre-contact, post-contact, former, and current Native American homelands.”

Timeline for NAGPRA

Under NAGPRA, there is an established 90-day timeline for repatriation with guidelines to follow.

Source: Eric Rothermel

This timeline allows for the tribe to initiate consultation among its members for items and human remains. Tribes are able to decide amongst themselves who will have the claim to the children who are culturally affiliated with them.

Army Guidelines Conflict

A source of tension between the tribe members and the United States Army is the Army’s policy difference.

Obed Hernandez/Unsplash

The Army is entitled to set its own guidelines for the return of anyone buried at Carlise. These guidelines say that a child can only be returned to the closest living relative and requests can only occur once a year. (via Native News Online)

The Army Doesn't Think NAGPRA Applys

In a Federal Register Notice published in 2021, the US Army argued that NAGRPA doesn’t apply to the Carlise Main Post Cemetery.

Source: Sgt. Devon Bistarkey/Wikimedia

They argued that “because the remains are not part of a collection” NAGPRA doesn’t and should not apply in this case. It’s unclear whether the NAGRPA law or the Army guidelines take precedence.

Indian Law Experts Argue the Law Does Apply

Experts in Indian law have argued that NAGPRA should be prioritized over Army policy. Shannon O’Loughlin, an attorney of the Association of American Indian Affairs, told Native News Online, “It does apply.”

.

Source: Katrin Bolovtsova/Pexels

“The Army Corps has just refused to follow NAGPRA and instead has created its own form and process. Federal law has precedent over agency policy,” Loughlin said

Fighting for Samuel Gilbert and Edward Hensley

The Winnebago Tribe is therefore arguing that the US Army has broken the law by refusing to return the remains of two of their ancestors, Samuel Gilbert and Edward Hensley, which the army has in their possession.

Source: Shutterstock

The tribe reported in the lawsuit that they presented a request to the Office of Army Cemeteries in October, but it was denied in December.

The Story of Samuel Gilbert and Edward Hensley

The reason why the Winnebago Tribe is asking for the remains of these two boys is because they are buried in an army cemetery in Philadelphia, thousands of miles from their homeland in Nebraska.

Source: National Cemetery Administration

Both Gilbert and Hensley reportedly died in 1895 and 1899, respectively, while attending the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. At that time, the boys’ tribe and family weren’t told that the boys had died, and they never saw their sons or their bodies again.

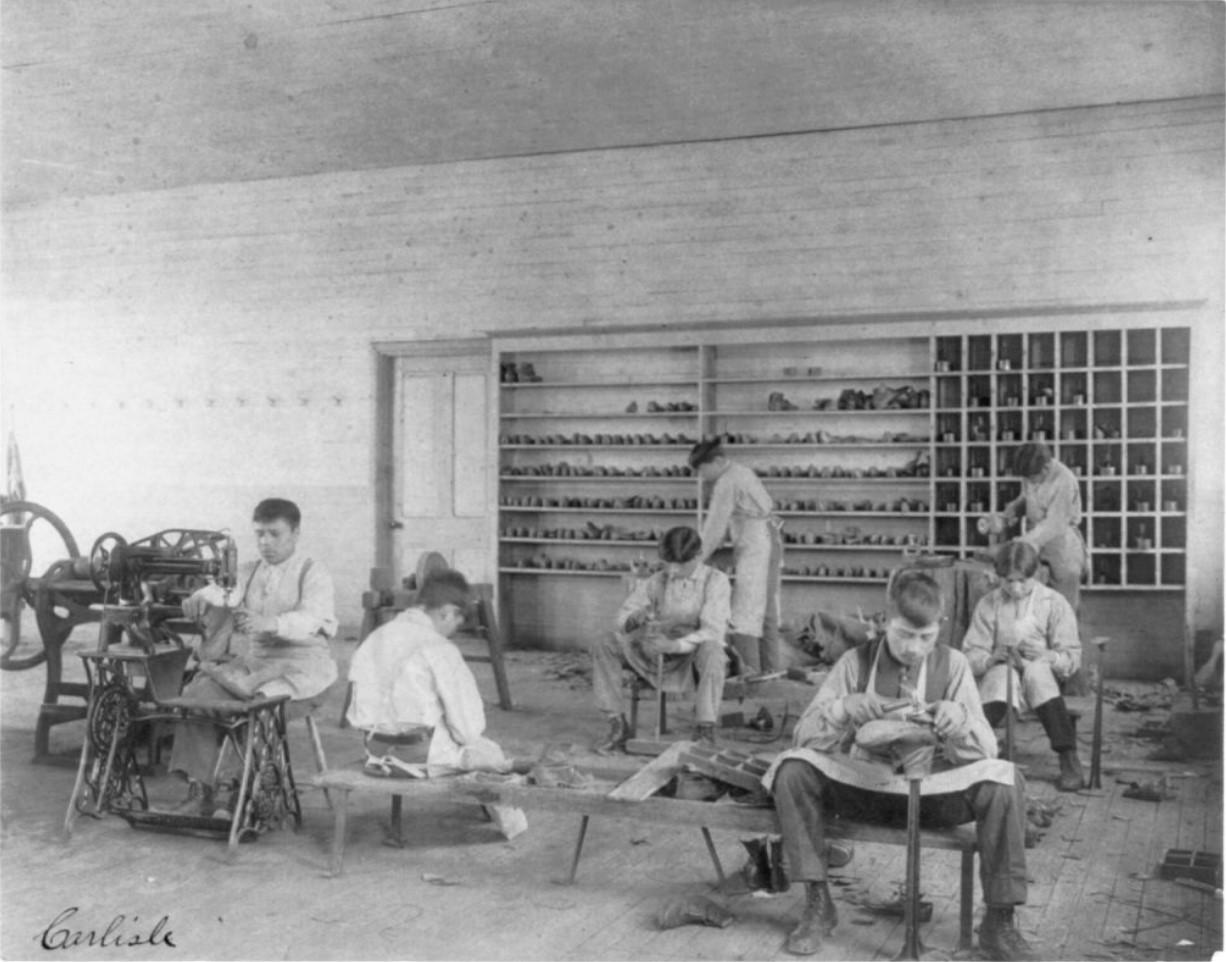

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania

The way in which the boys passed away and were buried was certainly controversial, but it’s important to understand that there were also issues with the boarding school itself.

Source: Heritage Art/Getty Images

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the first of many similar boarding schools, where young Native American boys were taken. Often, the children were removed from their homes without their families’ permission, and experienced extremely challenging conditions at the “schools” that led to their untimely death.

Young Native Americans Were Forced to “Assimilate”

The idea behind the boarding schools was that the Native American boys would be forced to assimilate American culture.

Source: Heritage Art/Getty Images

Army officials attempted to “bully the Native American out of them” by changing their names, punishing them for speaking the languages of their tribes, and cutting their hair. They even cut off their symbolic braids and forced the boys to dress in American military uniforms.

Unjust Deaths

According to Native News Online, the Carlisle Indian boarding school has around 194 indigenous children who are buried in the cemetery. When student deaths were announced in the local newspapers back in that time, the causes of death were abhorrent.

Source: Ajay Kumar Chaurasiya/Wikimedia

Death causes such as consummation and tuberculosis were named as well as unknown causes. This is especially egregious given that the children were forced into this environment.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland Is Asking the Government to Admit to Its Mistake

While the boarding schools are a horrific memory for many Native American tribes, for the rest of the country, this grave injustice is widely forgotten.

Source: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

However, Deb Haaland, the first Native American Interior Secretary, is trying to get the US government to admit their mistake and apologize to the descendants of the boys who were forced to attend and died in these schools.

The Army Remains in a “Position of Control”

Now, more than 100 years later, lawyers for the Winnebago Tribe are arguing that just like when they ran the schools, the army is still mistreating Native Americans.

Source: Larry W. Smith/Getty Images

One of the attorneys, Grey Werkheiser, explained, “The Army always sought to maintain a position of control, dominance over native peoples while they were alive — and while they were dead.”

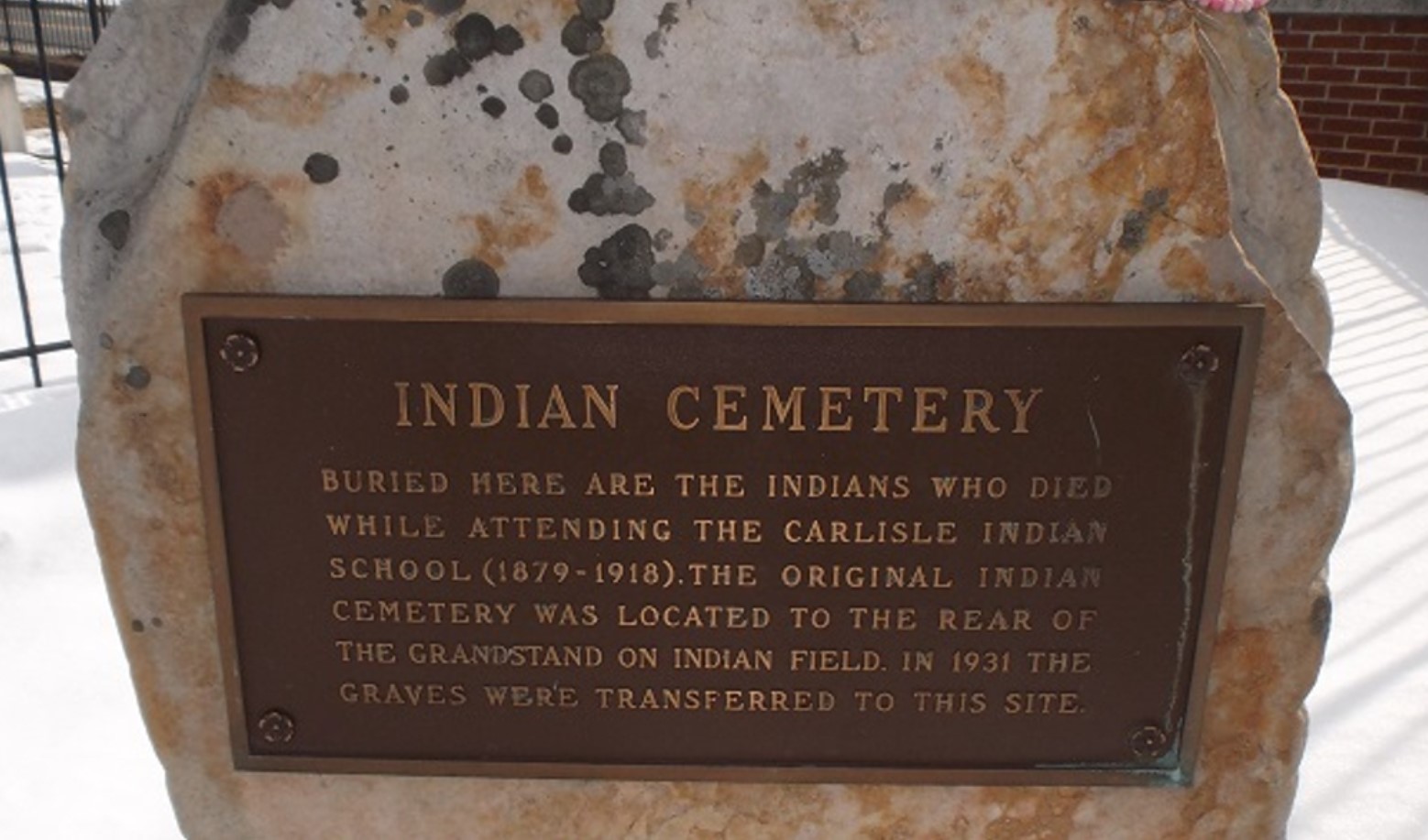

The Winnebago Tribe Argues Their Graves Are Now a Tourist Attraction

In addition to breaking NAGPRA protocol, the lawsuit also states that the graveyard where Gilbert and Hensley are buried is used as a “tourist attraction.”

Source: Office of Army Cemeteries

A spokesperson for the Office of Army Cemeteries responded that the cemetery is, “Absolutely not treated as a tourist attraction.” However, people can visit and there is a sign at the entrance, “Indian Cemetery”, naming the area where the boys, and many like them, are buried.

The Army Claims the Boys Were Buried with Dignity

The spokesperson also said in a statement, “The cemetery is a dignified resting place demonstrating respect and care of all the deceased buried there.”

Source: Office of Army Cemeteries

However, the Winnebago Tribe doesn’t believe the cemetery is a dignified resting place. And, more importantly, that it isn’t the right place. They are arguing in court that the boys deserve to go home.

Previous Success For Returns

In 2017, a Northern Arapaho woman named Yufna Soldier Wolf was successful in petitioning the army for the return of three tribe children. (via Native News Online)

Source: Brett Axelberg/Wikimedia

The process was formalized by the Office of Army Cemeteries with that case for returning Native youth. A total of 21 children buried at Carlisle school cemetery have been returned over the course of four transfer ceremonies since then.

Carlisle School Cemetary Versus Carlisle Main Post Cemetary

Although the Army has paid for transfer ceremonies in the area before, the crux of the issue is where the bodies are located. The army argues that Carlisle Main Post Cemetary has different rules that make it exempt from disinterment.

Source: JL/Google Reviews

“Under army policy, and because we have the custody of the remains, we have to allow the family to be the one that notifies us,” Renea Yates, the director of the Office of Army Cemeteries, said. “Tribal requests cannot be made. It has to be the individual, closest family member.” (via Native News Online)

O'Loughlin Disagrees

O’Loughlin rebutted this argument, viewing this policy as putting undue pressure on Native families.

Source: Tingey Injury Law Firm/Unsplash

“What happens if there’s no linear living descendant?” asked AAIA’s O’Loughlin. “I think it’s good of them to reach out to the tribes and say ‘these are the children affiliated.’ But then to require the families to have to come forward may be difficult for many, many reasons,” O’Loughlin said. (via Native News Online)

The Winnebago Tribe Desperately Wants the Boys to Rest in Peace

Beth Wright, an attorney from the Native American Rights Fund, explained, “The way Winnebago views it is that the boys have been waiting to come home for nearly 125 years.”

Source: Robert Alexander/Getty Images

Wright continued, “Their spirits can’t rest and they can’t go on unless they are returned to the place that they were taken from.”