Lucy Reveals Truth About Early Humans, But She Wasn’t Alone

Over half a century ago, researchers scouring the plains of Africa stumbled upon the fossilized remains of an ancient hominin from the genus Australopithecus afarensis dating back millions of years.

In the five decades since the find, once considered “the mother of us all,” a thorough examination of the skeletal remains has shed considerable insight into the evolution of hominins and led researchers to discover a fascinating truth about early humans.

The Ancestral Lineage of Modern Humans

Today, all humans on Earth, including us, are descendants of the Homo-sapiens genus.

Source: Wikimedia

While there were once several other species in the Homo genus, for various reasons, the last of the different groups went extinct around 40,000 years ago, leaving modern humans as the sole surviving hominin on Earth.

The Emergence of Homo Sapiens

Despite the disappearance of various species from the homo genus, archaeologists have unearthed the fossilized remains of ancient humans. This has allowed paleontologists to study the long evolution which led to the emergence of homo sapiens.

Source: Wikimedia

One of the most fascinating discoveries of the past century was the fossilized remains of an ancient human named Lucy, a female of the genus Australopithecus afarensis, thought to have walked Earth around 3.2 million years ago.

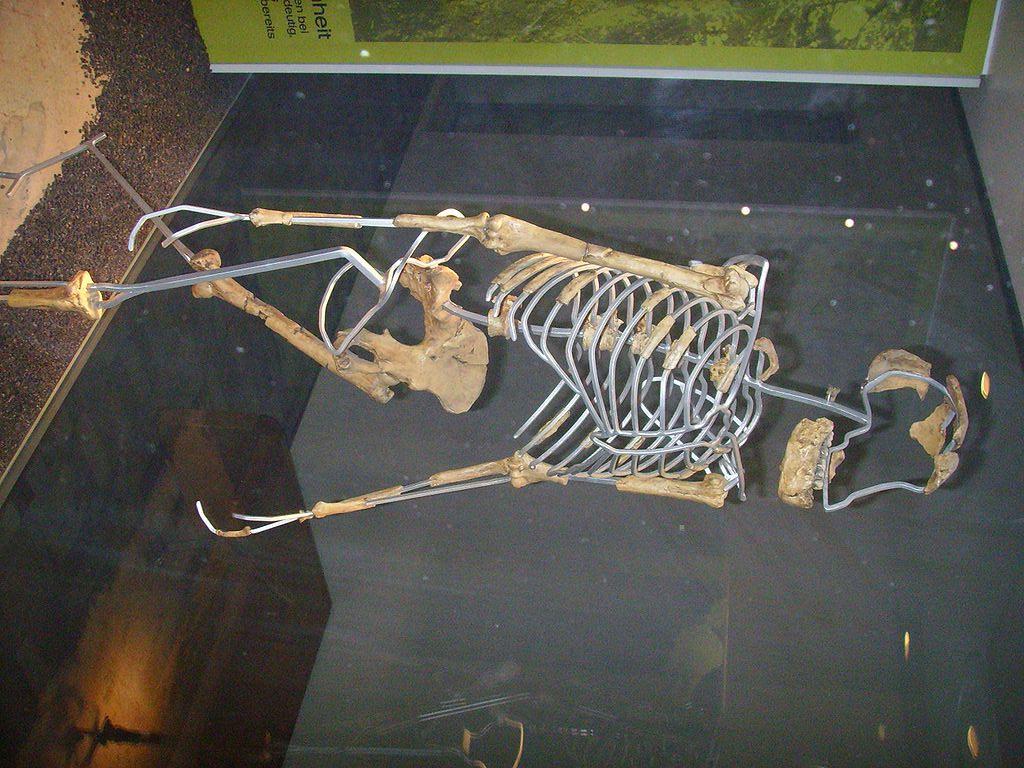

Anthropologist Stumbles Upon Remains of Ancient Human

Donald Johanson, an anthropologist from the US, had been searching the Afar region of Ethiopia in 1974 for fossilized animal bones when he and his student stumbled upon the remains of a tiny arm bone. This was the discovery of Lucy.

Source: Wikimedia

“We looked up the slope,” Johanson recalled. “There, incredibly, lay a multitude of bone fragments – a nearly complete lower jaw, a thighbone, ribs, vertebrae, and more! Tom and I yelled, hugged each other, and danced, mad as any Englishman in the midday sun!”

The Long-Lasting Implications of the Discovery

Forty-seven bones were unearthed in Ethiopia, making up nearly 40% of a complete skeleton. It’s now been almost five decades since the discovery, yet it remains the greatest breakthrough in the history of human paleontology.

Source: Wikimedia

The discovery was unique for several reasons, one of which solved a long-standing debate in the scientific world, one that went against the theories proposed by Charles Darwin.

What Came First: Bipedalism or Large Brains?

Speaking on the evolution of hominins and the features that make us inherently human, Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist from the Natural History Museum of London, explained, “Human beings have three key attributes: our ability to walk upright, our capacity to make tools, and our large brains.”

Source: Wikimedia

He continued, “But a crucial question is: which of these features arrived first in our evolution? What was the first step that led our ancestors to move down a road that ultimately led to the appearance of Homo sapiens?”

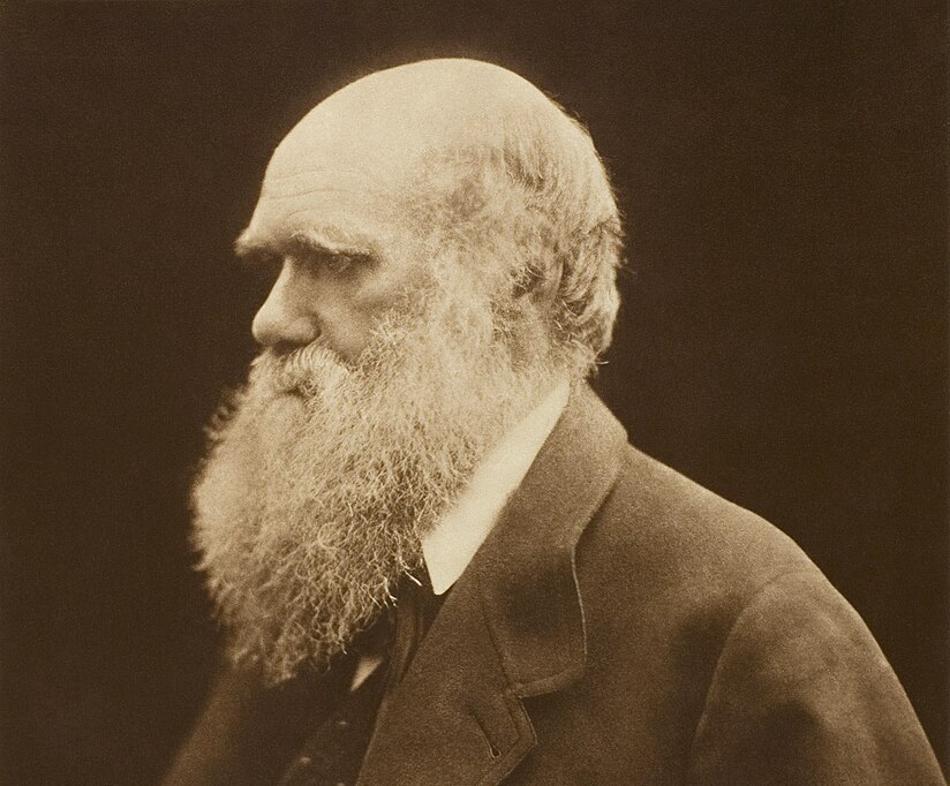

Lucy Goes Against Theories in “The Descent of Man”

Darwin’s “In The Descent of Man” proposes that the three human features, large brains, bipedalism, and tool-making, evolved in this order, suggesting that one played a role in the evolution of the next.

Source: Wikimedia

Based on his assumption, brain enlargement must have come early in human evolution, an idea accepted by the scientific community until the discovery of Lucy.

The Discovery of Lucy Dismisses Darwin's Theory

Lucy’s discovery revolutionized our understanding of human evolution, refuting Darwin’s idea that humans with larger brains came before our ancestors walked on two legs.

Source: Wikimedia

“Lucy showed that this idea was simply not true,” says Stringer. “Her skeleton showed our ancestors walked on two feet long before their brains got big.”

Large Brains Don’t Define Ancient Humans, Says Palaeoanthropologist

Stringers’ point was backed up by Zeresenay Alemseged, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Chicago, who suggested that large brains were not a defining factor in what constitutes a human millions of years ago.

Source: Wikimedia

“Lucy showed that a big brain was not the sine qua non of being a member of the human lineage,” he said.

Lucy and Her Crude Tools

Lucy’s brain was only a bit bigger than an ape’s, but her hand was probably capable of smashing bones for marrow with crude tools, says Sonia Harmand of the French national research agency CNRS.

Source: Jumbuk73/Pixabay

“We don’t know if Lucy was a toolmaker,” Harmand emphasizes. “Unfortunately for her, she has a lot of competition” from other hominin alive at the time.

Hominins in Africa 4.5 Million Years Ago

A question that continues to puzzle researchers is whether Lucy and her kin, the Australopithecus afarensis, meaning “the Southern Ape from Afar,” are the direct ancestors of Homo sapiens.

Source: Wikimedia

In the decades that followed the discovery in Ethiopia, even older hominin species were discovered, including the Australopithecus afarensis, which dates back over 4 million years, and the Ardipithecus ramidus, which lived around 4.5 million years ago in Kenya and Ethiopia.

Originator of the Lineage

Despite some researchers suggesting the discovery of even older hominins likely means Lucy and her relatives were a side branch of the lineage that led to Homo sapiens, Alemseged disagrees, proposing that afarensis may be the originator of the lineage that led to modern humans.

Source: Wikimedia

“These earlier hominins probably walked upright for some of the time, but many were probably living in trees for most of their lives. In contrast, Lucy and her afarensis kin were spending a great deal of time walking upright. They were pivotal in the transformation of our genus into one that became committed to an upright stance,” he said.

The Rise of the Homo Genus

Since the discovery of Lucy’s fossilized remains in the 70s, researchers have found afarensis in Tanzania, Chad, Kenya, and Ethiopia, and we know Lucy and her kin must have lived in these parts of Africa for close to a million years,” adds Alemseged.

Source: Wikimedia

He continued, “That antiquity and extensive geographical spread convince me that it is the most likely candidate to have given rise to the many species of the Homo genus and ultimately to our own species, Homo sapiens.”

Lucy Wasn’t Alone

Five decades of research found that Lucy walked upright despite her small brain and apelike upper body. While she likely climbed trees to feed, nest, or escape predators, Lucy was able to flourish and evolve through her offspring.

Source: Freepik

More than 400 fossils of males and females, as well as the Kikika child, have revealed how Australopithecus afarensis grew, socialized, and evolved during its million years on Earth nearly 3 million years ago.

Not the Earliest Member of the Human Family

However, research has found that Lucy is no longer the earliest known member of the human family. Researchers believe that Lucy wasn’t alone in the grassy woodland.

Source: Freepik

“We have multiple [hominin] species in the same time period,” Yohannes Haile-Selassie, director of the Institute of Human Origins (IHO) at Arizona State University, said to Science.

The Aunt of Homo Sapiens

While Lucy is more like a great-great-great-aunt than a direct human ancestor, her fossil is a better candidate for being the mother of every human being.

Source: Wikimedia

“The real importance of Lucy is we didn’t know what an early human ancestor looked like,” says Don Johanson, founder of IHO. “I was struck by her more apelike features,” he says.

This Discovery Sparked the Conversation

Lucy was the first hominin to push back the age of the human gene to a time closer to when geneticists thought the ancestors of humans had split from the ancestors of chimpanzees.

Source: Berkeley Lab/Flickr

Lucy “entered a field actively debating the antiquity of the chimp/human split,” says Tim White, a paleoanthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley. White co-authored that 1978 paper describing Lucy’s species with Johanson and paleoanthropologist Yves Coppens.

Changing the Narrative

“Once upon a time, life was relatively simple because anything before 3 million years was A. afarensis … [and] it was the mother of us all,” says paleontologist Fred Spoor of the Natural History Museum in London. “That was the gospel.”

Source: Pixabay/Pexels

But other species—some of which are much older than Lucy—have emerged.

Homo Links Extend Further

There was an intense search for Lucy’s ancestors in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia in the mid-1990s. They found crushed but complete partial skeletons they named Ardipithecus ramidus, which dated back 4.4 million years ago.

Source: Freepik

Haile-Selassie revealed a lower jaw, teeth, and disarticulated bones of the hands, feet, and arms of Ardipithecus kadabba, dating back 5.8 million years. These primitive hominin looked more like upright apes than humans.

Pushing Human Lineage Back

Other fossils pushed the human lineage even further. A thighbone from an apparent upright walk from Kenya, called Millennium Man, dates back to 6 million years ago.

Source: Wikimedia

The skull of Chad, or Sahelanthropus tchadensis, dated 6 to 7 million years old.

Aging Humans

But what makes these upright walkers the great-great-great-grandparents of modern humans? It’s a fierce debate that anthropologists have been having for years. Are these species considered hominins, and how do they relate to Australopithecus.

Source: Roberto Nickson/Unsplash

One thing is clear: the human family dates back to at least 6 million years ago, a date that aligns with the most recent genetic evidence for the timing of the split between human lineage and chimp.

Contenders for Our Ancestors

Africa seems to be home to a diverse set of hominins, all of which are contenders to be the ancestors of Homo. One contender is the Kenyanthropus platyops, which has a flatter face and smaller molars than Lucy’s species.

Source: Pavel Švejnar/Wikimedia Commons

These traits suggest it was intermediate between Lucy and Homo. However, more evidence of the Kenyanthropus is needed.

Lucy Is Still Considered Our Shared Link

Scientists believe that Lucy and other species, which would later help create modern humans, walked the Earth together between 2 and 3 million years ago.

Source: Freepik

But researchers do not believe that there is a convincing forebear of Homo when compared to Lucy. No fossils unequivocally bump her species from its spot as the original ancestor of early Homo.

The Challenge of Finding Ancestors

Identifying the direct ancestor of Homo is challenging because “we don’t know much about early Homo,” says Carol Ward, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Missouri. The earliest known fossil of our genus is a lower jaw with worn molars from 2.8 million years ago.

Source: Wikimedia

According to Science, “‘“It’s a convincing case,” Ward says, “but it’s just one mandible until about 2 million years ago,when at least two members of the genus, Homo habilis and H. erectus, appear elsewhere in eastern Africa.”