Myths About the Civil War That Have Been Entirely Debunked

The American Civil War is a central and tumultuous chapter in U.S. history, one which is often marred by misconceptions.

The longer these myths linger, the more difficult it will be for a comprehensive understanding to emerge that encompasses the complexities surrounding this larger-than-life conflict. Here we debunk a number of prevalent and persistent misconceptions, throwing a light on the lesser-known aspects of the American Civil War.

Lincoln’s Policies Were Not Completely Supported by the North

The Civil War’s narrative extends beyond a simple North-South dichotomy. Even in the North, dissent simmered, manifesting through groups like the “Peace Democrats” or “Copperheads.”

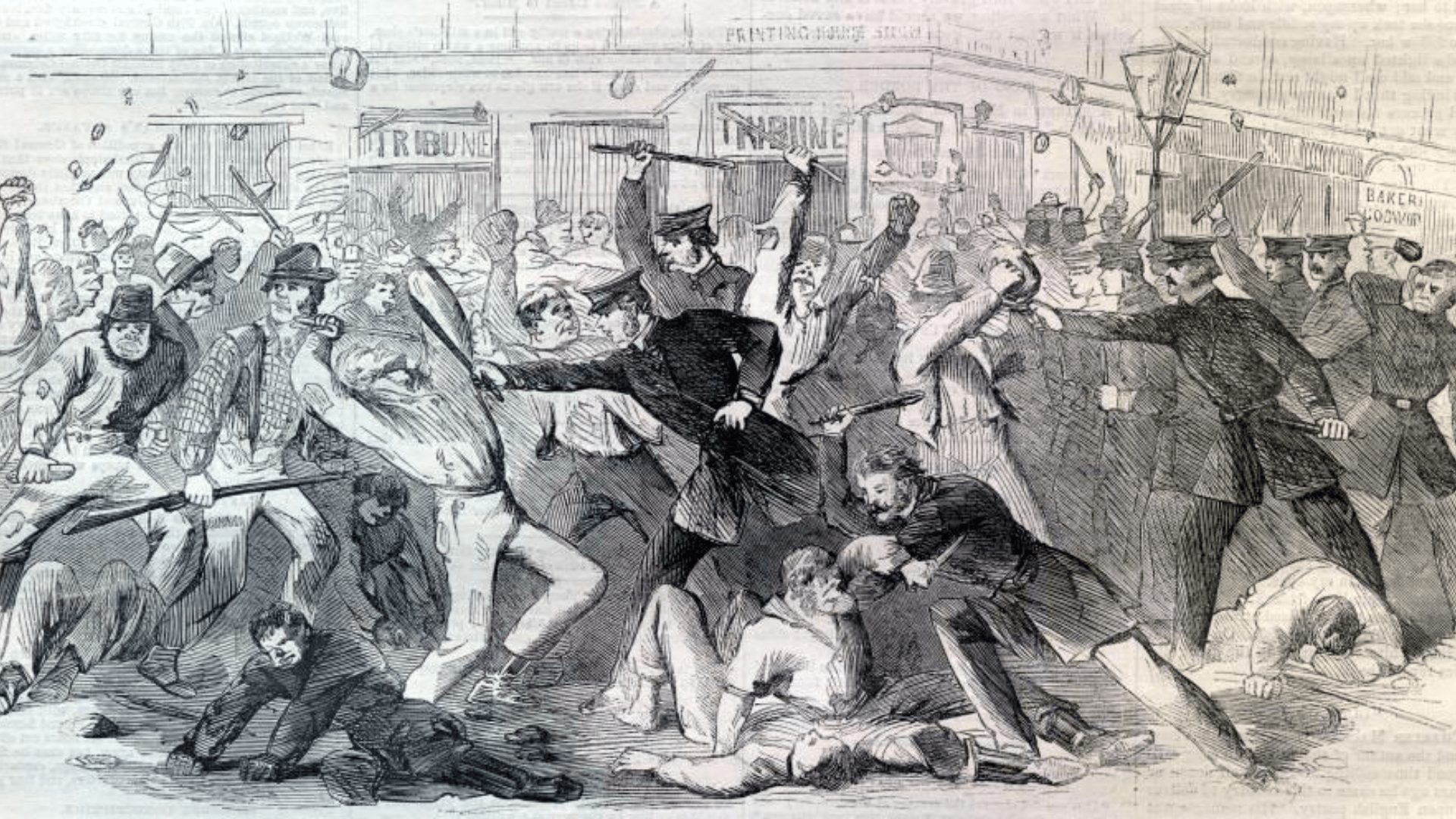

Harper's Weekly/Wikimedia Commons

Led by figures like Governor Horatio Seymour of New York, these dissenters opposed Lincoln’s leadership and the war itself. The Civil War Draft Riots of 1863 exemplify the depth of this dissent, as working-class citizens, angered by the Enrollment Act, engaged in violent acts against African Americans and their establishments.

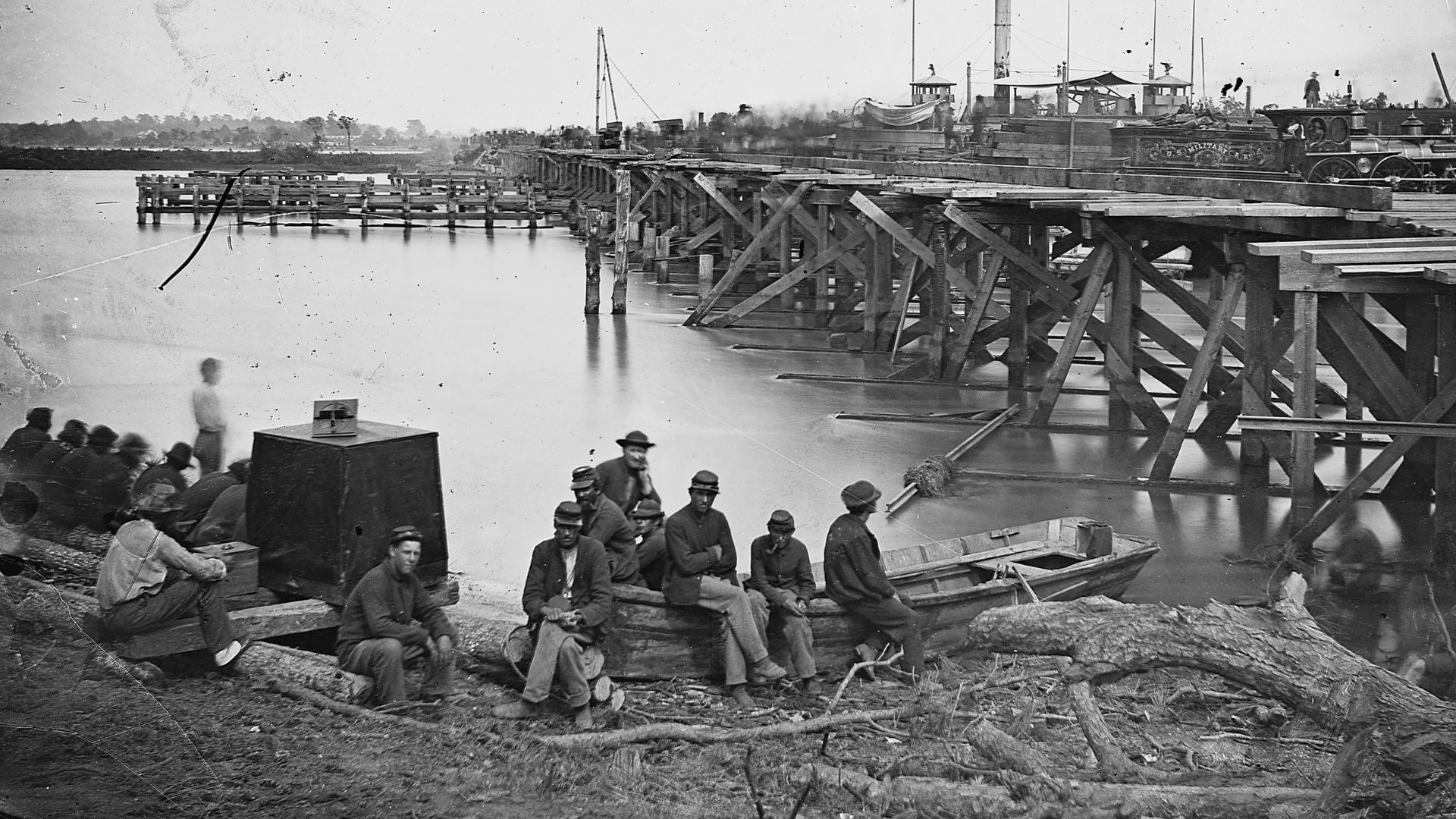

Many Soldiers Weren’t Volunteers

Whether people are talking about the Union or the Confederate armies, often they claim that the moral fight between the two got regular people up in such a fervor that the entire armies were made up of volunteers.

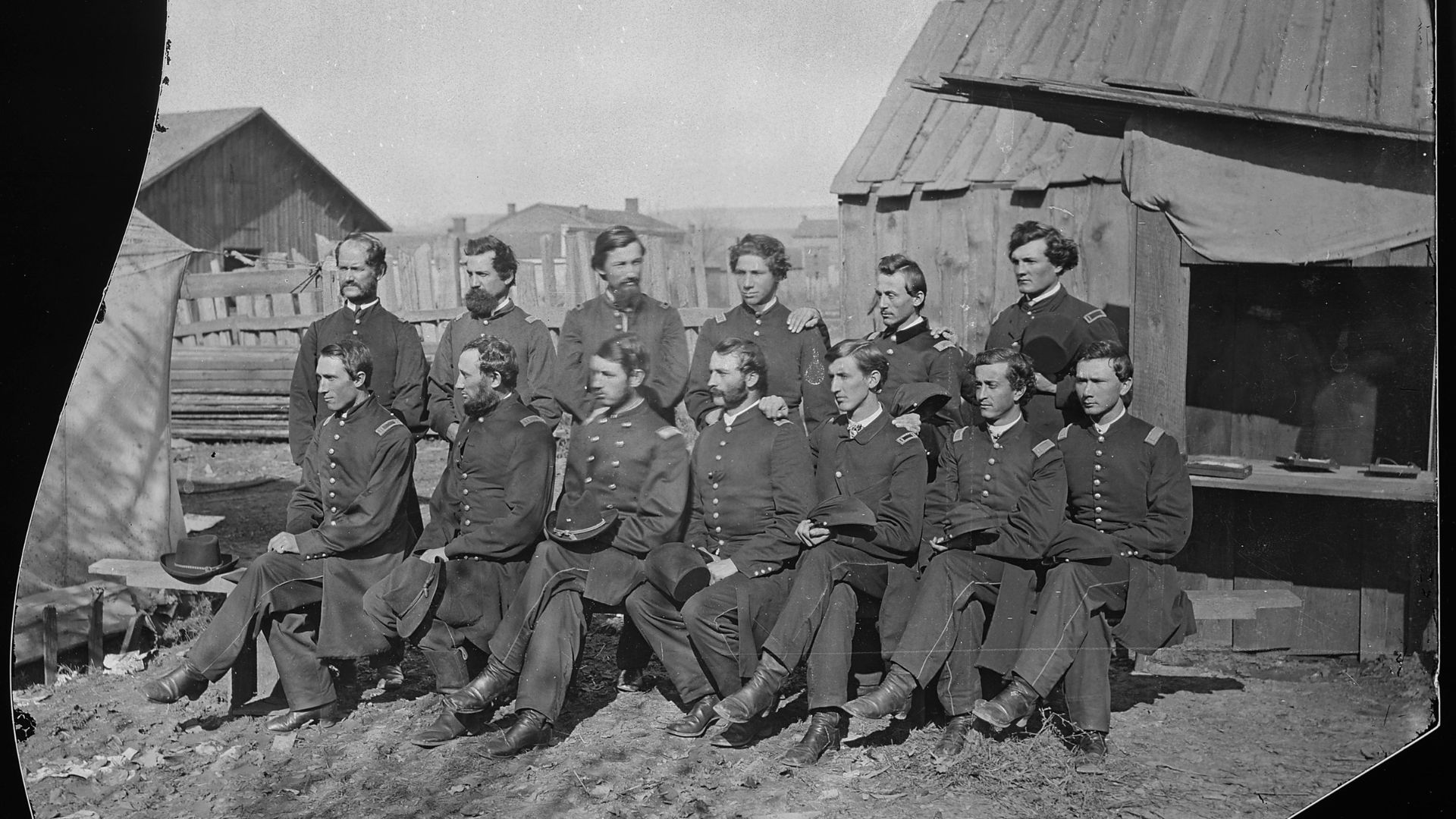

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

While many did volunteer to fight in the war, this isn’t completely true. Many men were also conscripted in the draft. The Confederacy even passed the first draft laws in U.S. history in 1862. Meanwhile, Northern states drafted men in both 1863 and 1864.

Many Immigrants Fought in the War

Another myth is that this war was only fought by Americans, against Americans. In fact, many immigrants who had recently arrived to make a new home in the country ended up fighting in the war.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Documents have proven that many German, Irish, and Scandinavian immigrants fought for the Union, among many others. Now, it is thought that about a third of the entire Union Army consisted of immigrants or foreign-born people.

The Irish Weren’t Recruited Right Off the Boat

Another new myth that has recently appeared is the idea that Irish immigrants were recruited into the Union Army right after they stepped off the boat and onto American soil.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

While there were many Irish immigrants who fought for the Union, this little scenario isn’t true. However, it is true that many immigrants from Ireland disagreed with the war. The draft riots in New York in 1863 were mainly conducted by Irish immigrants who disagreed with the ongoing war’s policy and drafting.

The Civil War Started Because of Slavery

There’s been some controversy in the centuries since the Civil War about why the war started in the first place. Though many have claimed that it didn’t start because of slavery, this is a myth. One of the main causes of the South seceding was slavery — and, most importantly, the economics of slavery.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Southern and northern states weren’t on the same page on the politics and economics of slavery. The South also didn’t want Abraham Lincoln as their president. All of this also had to do with states’ rights.

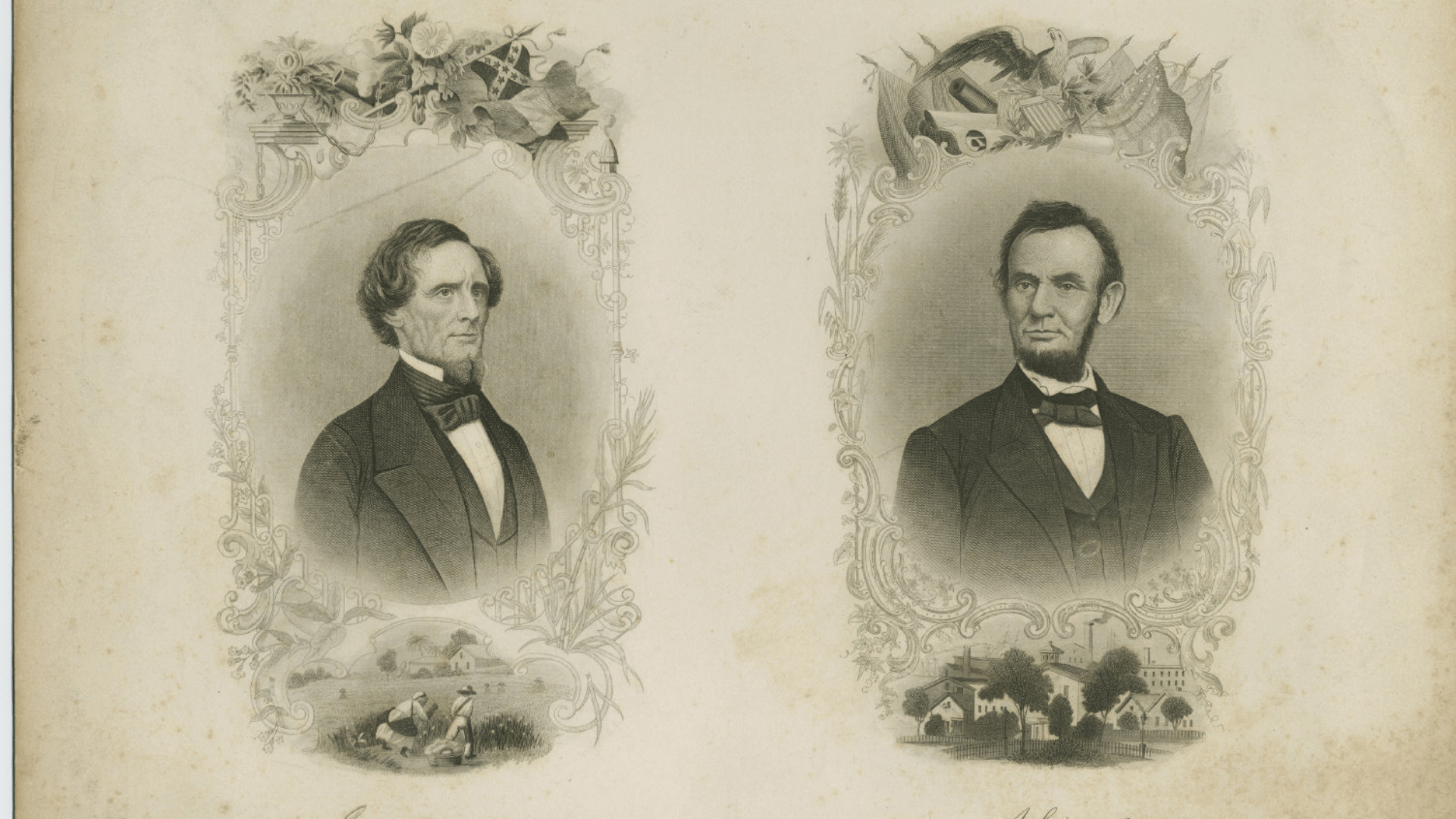

Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee Weren’t Committed Secessionists

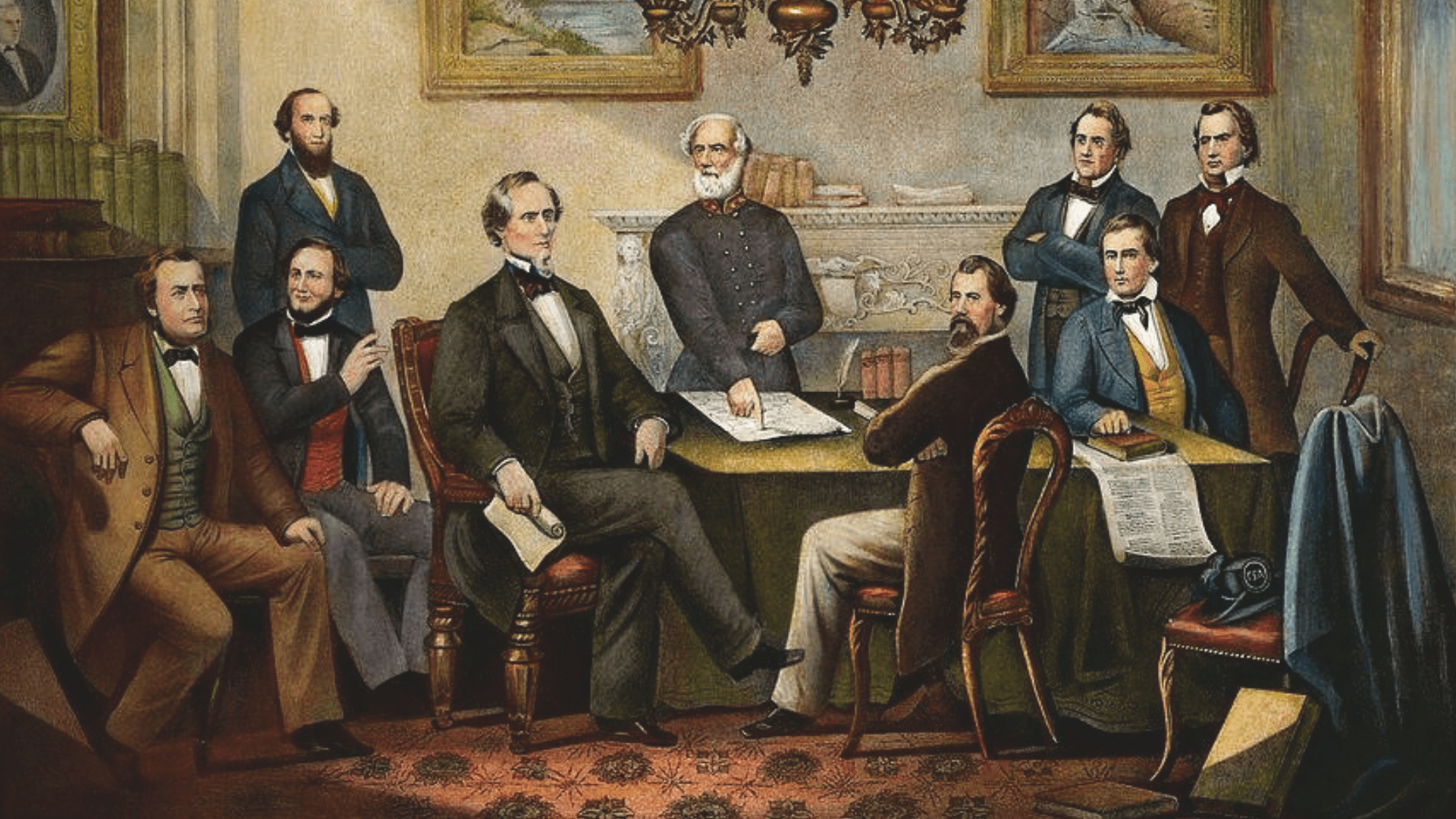

Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s president, initially opposed secession, showcasing the nuanced stance many held during this tumultuous period.

Thomas Kelly/Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, General Robert E. Lee, while initially hesitant about secession, aligned with his home state of Virginia when it seceded. The prevailing ideology, however, revolved around the question of slavery, with Davis staunchly defending it as a “moral, social, and political blessing.”

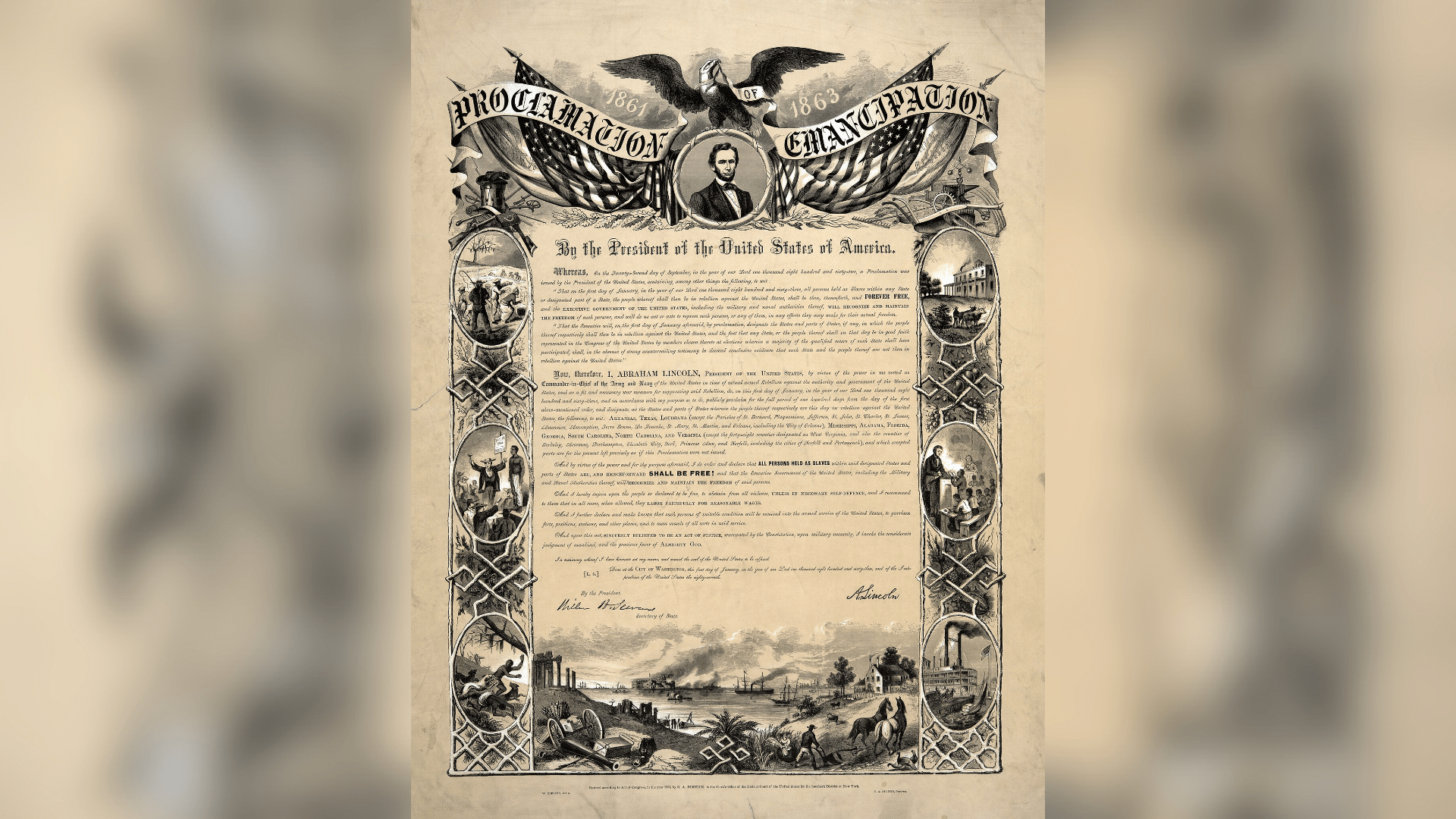

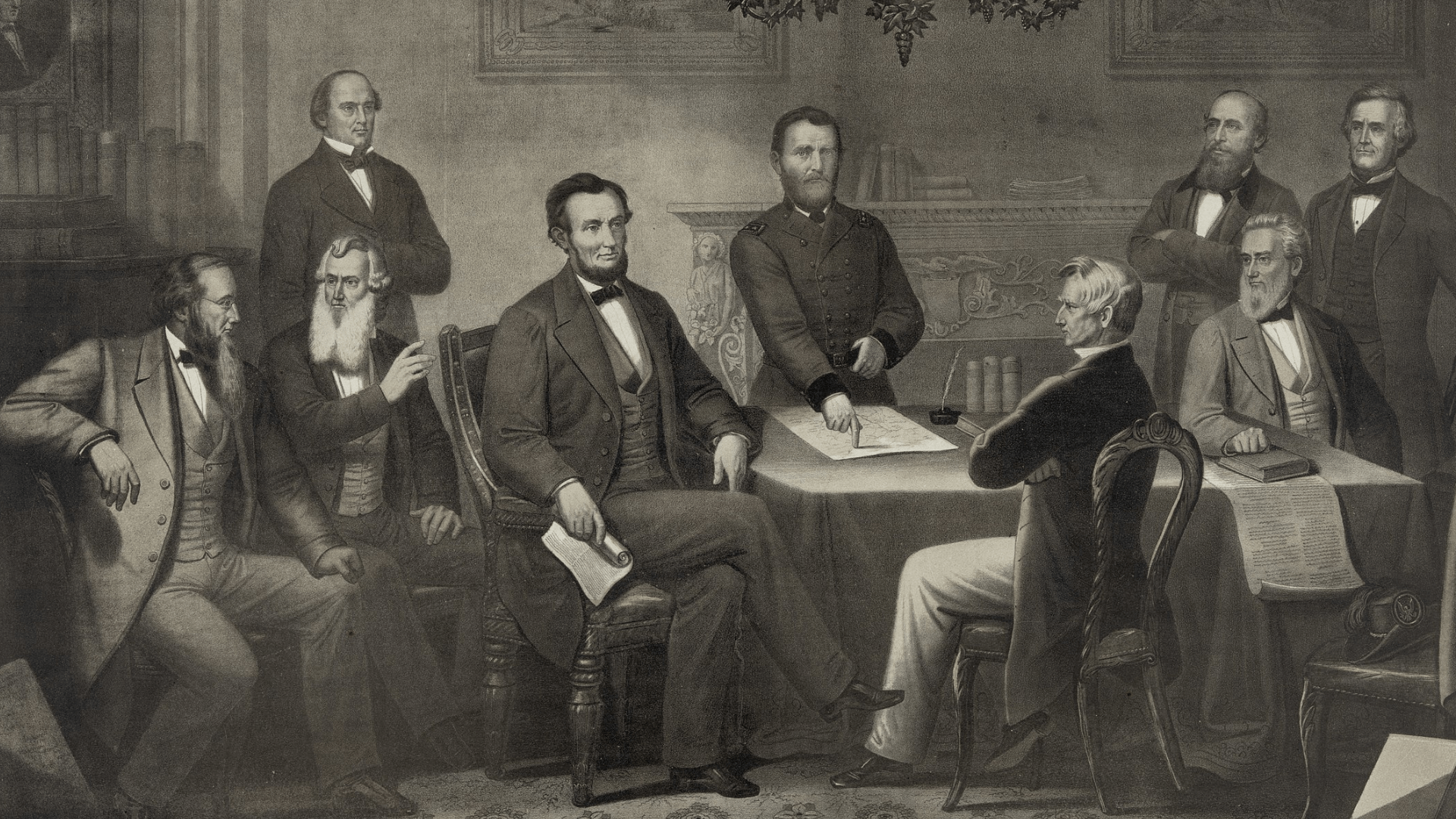

The Emancipation Proclamation Did Not End Slavery

While the Emancipation Proclamation marked a significant turning point by declaring slaves in rebelling states free, its impact had limitations.

Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

It excluded border states like Kentucky and Delaware, and its efficacy hinged on the Union’s victory.

The Civil War Was Not the Second American Revolution

The idea that the Civil War was the second American Revolution was first brought forth by historians Charles and Mary Beard in 1927. However, some critics say this is a myth, as the American Revolution was about equality among men. Meanwhile, notable leaders in the South in the 1800s publicly stated that the founders were wrong about equality.

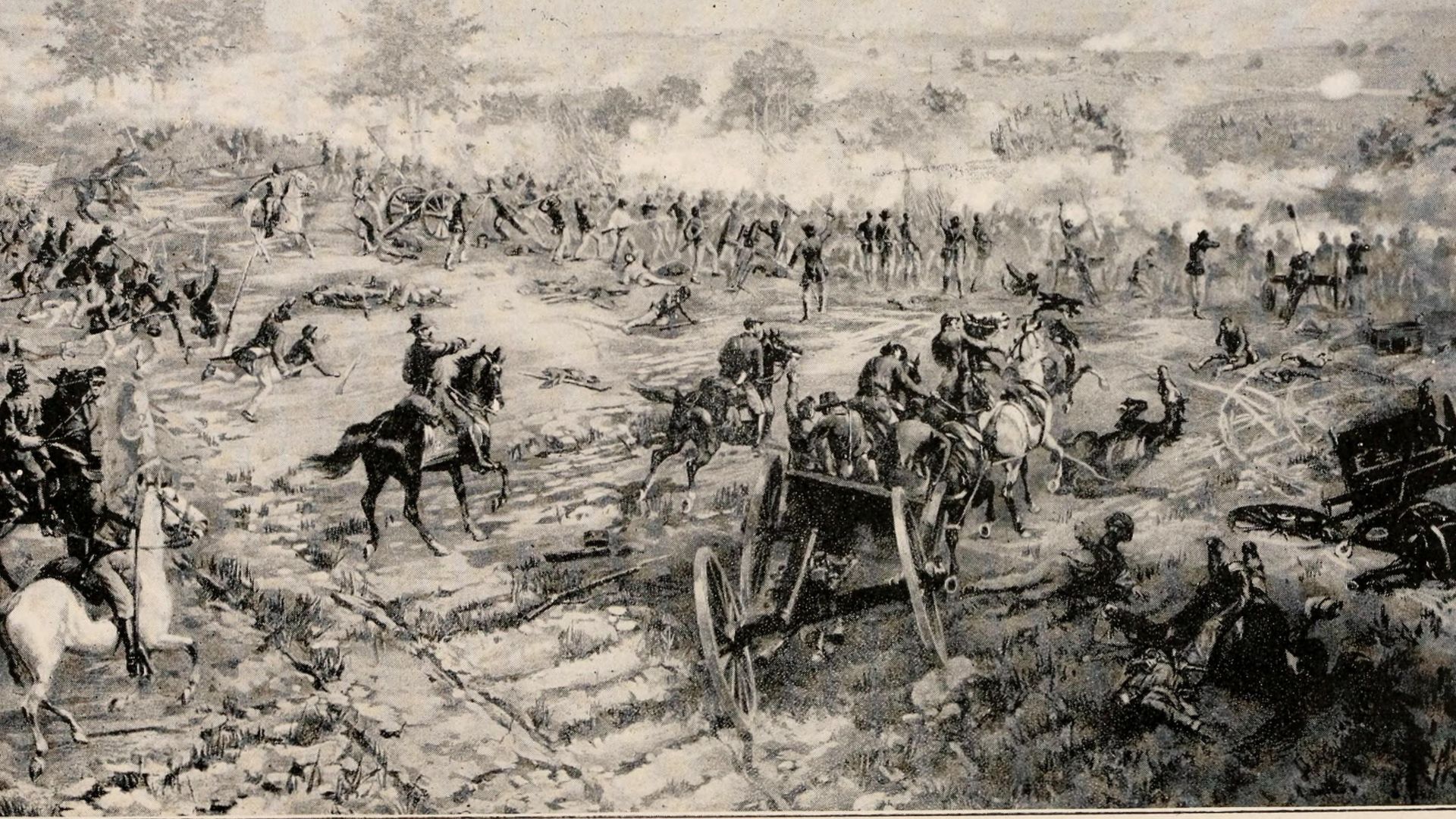

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

The Confederate’s Vice President Alexander A. Stephens discussed this inequality of man and disagreed with the founders in 1861. Stephens said, “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

The “War of Northern Aggression” Is a New Phrase

Sometimes, the Civil War is called the “War of Northern Aggression.” This phrase didn’t really appear during the era of the Civil War. It was simply never called this.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

This phrase didn’t begin to appear popularly in society until the 1950s during the Jim Crow era. Segregationists came up with the phrase as they tried to compare their efforts against segregation to the Civil War.

There Were Many Old Soldiers

When we think of war, we think of young men going into battle. When it comes to the Civil War, that is mainly true. Most of the soldiers ranged in age from 18 to 45.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

However, there is ample evidence that suggests there were many elder soldiers in the war. While the Union Army mainly only had under 30 soldiers, some Confederate soldiers enlisted in their 50s, 60s, and even 70s.

When Did Slavery End in the United States?

Slavery persisted until June 19, 1865, when Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, announcing the freedom of all enslaved people.

Source: Heathart/Wikimedia Commons

The 13th Amendment in December 1865 solidified the end of slavery in the United States.

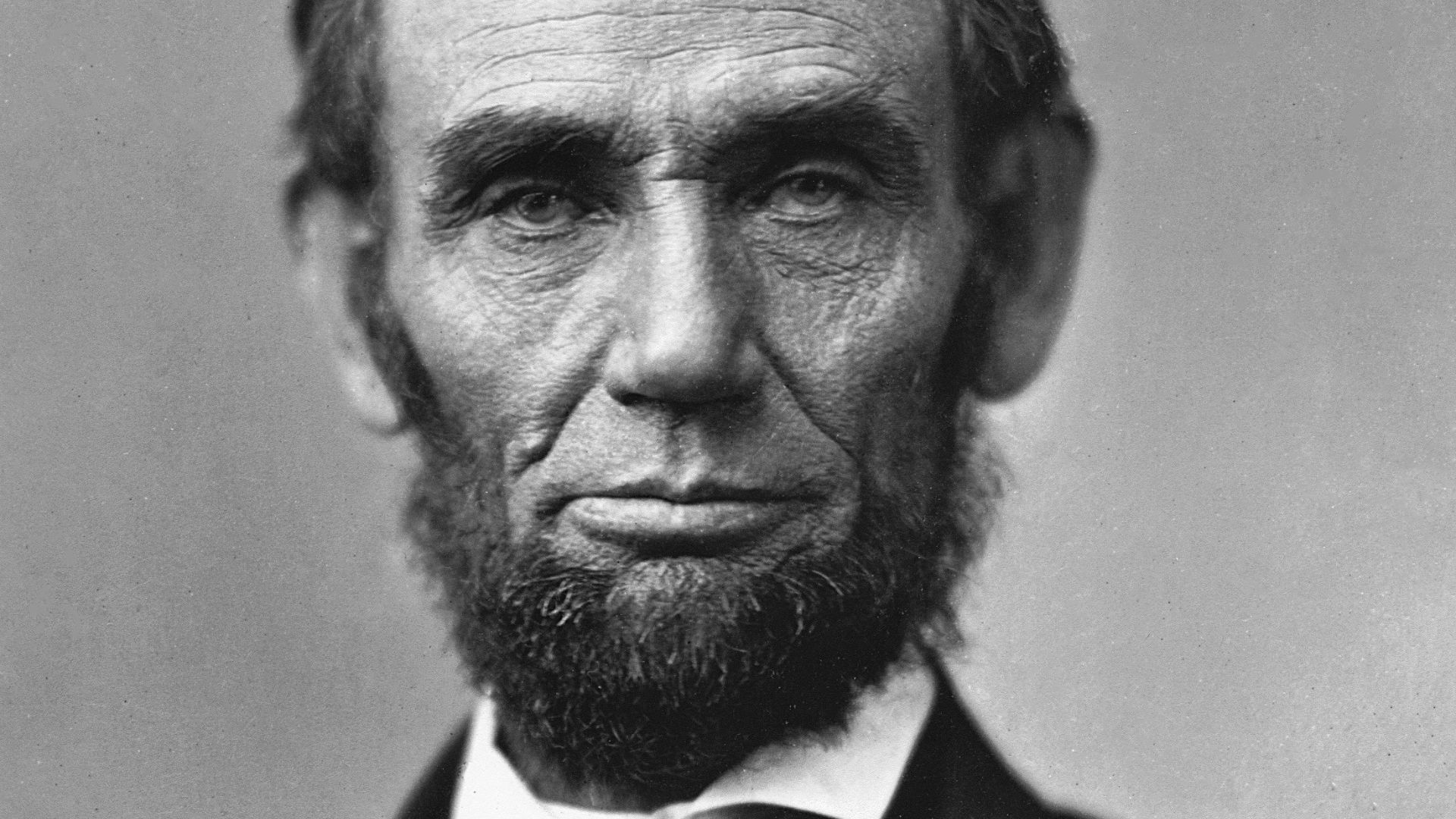

Abraham Lincoln Was Not an Abolitionist

Lincoln believed that slavery was wrong. That is a fact. This can be seen in the many writings and speeches he gave throughout the 1850s. However, he was no abolitionist.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

In fact, Lincoln thought that abolitionism was an even greater danger to the United States’ republic than slavery was.

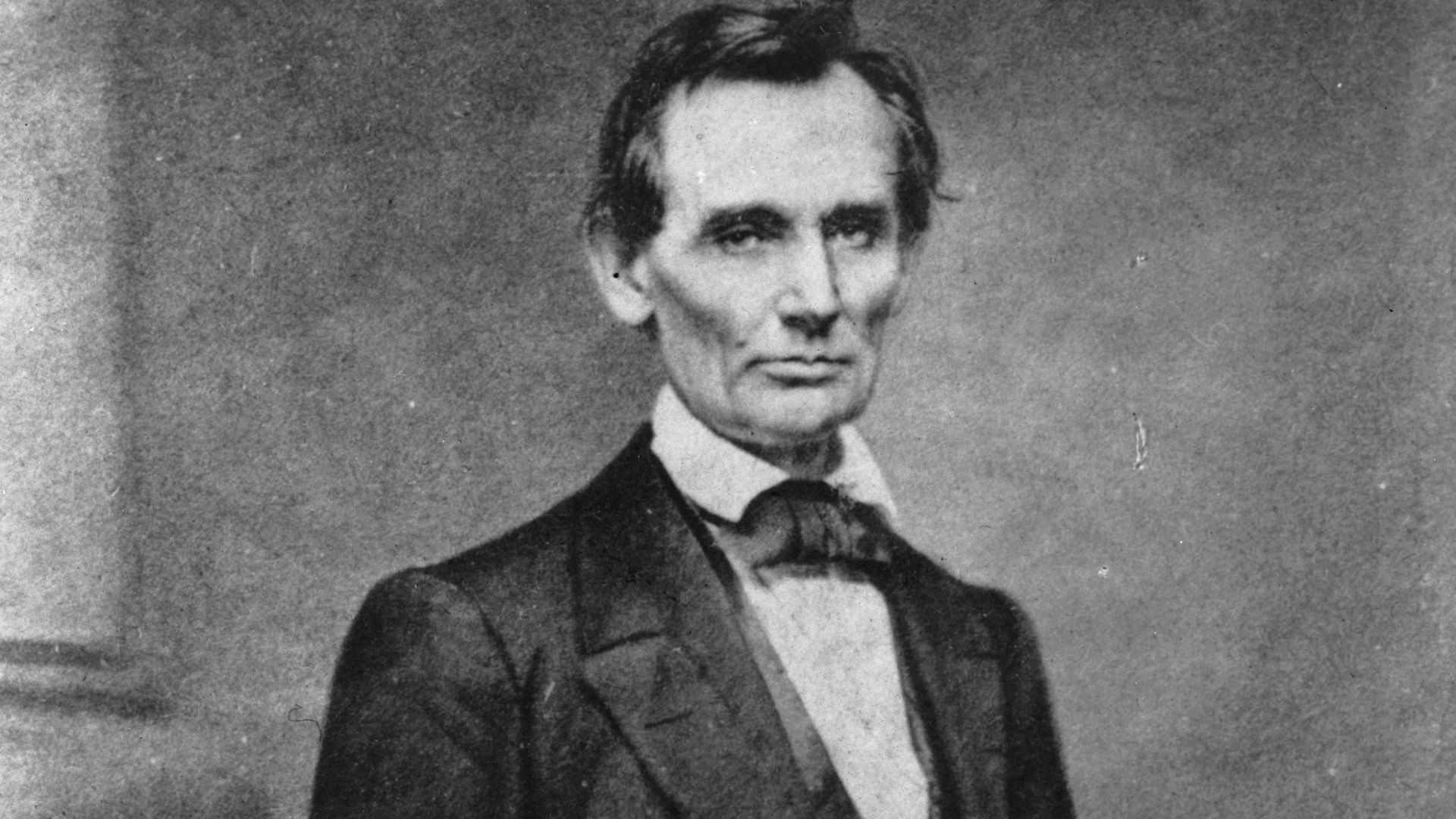

Abolitionists Didn’t Fully Support Lincoln

As Lincoln never claimed to be an abolitionist — even though he didn’t agree with slavery and did work to end it — the president never fully got many leading abolitionists’ support until much later on.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

This is because abolitionists knew what needed to be done. Slavery needed to be abolished, something Lincoln didn’t outright call for in the early 1850s thanks to what could be done under the Constitution. However, once emancipation and the 13th Amendment rolled around, abolitionists finally fully supported Lincoln.

95 Percent of Civil War Amputations Were Done with Anesthesia

Contrary to cinematic portrayals, anesthesia, particularly ether and chloroform, was used in around 95 percent of Civil War surgeries.

New York Public Library/Wikimedia Commons

While not without controversies, advancements in medical practices allowed for a substantial use of anesthesia during this period.

Amputated Body Parts Were Treated With Respect

Oddly enough, some rather graphic myths about surgeons on the Civil War battlefield have permeated into our present day. One misconception is that doctors even flung amputated body parts, such as arms and legs, out of windows.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

This isn’t true — though rather dire situations of this sort may have occurred. However, it wasn’t common, at all. For the most part, any amputated body part was treated with respect and was often buried.

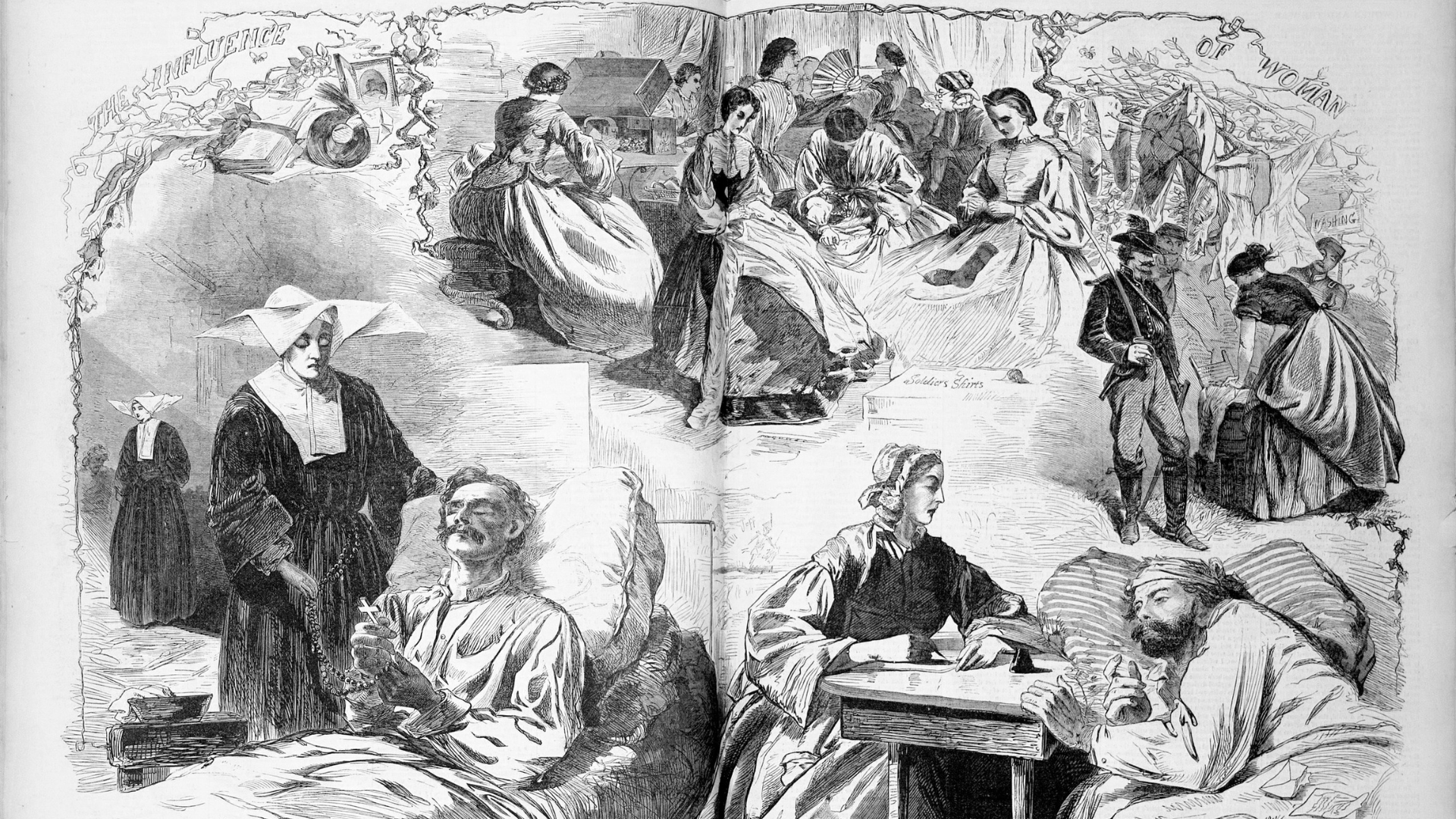

Women Also Fought in the Civil War

Despite legal restrictions, numerous accounts reveal that women clandestinely participated in the Civil War, with estimates ranging from 400 to 750 women taking up arms.

Harper’s Weekly/Wikimedia Commons

Disguised as men, some managed to infiltrate the front lines, engaging in activities such as spying, reconnaissance, and combat. Jennie Hodgers, fighting as Albert Cashier, exemplifies one such individual.

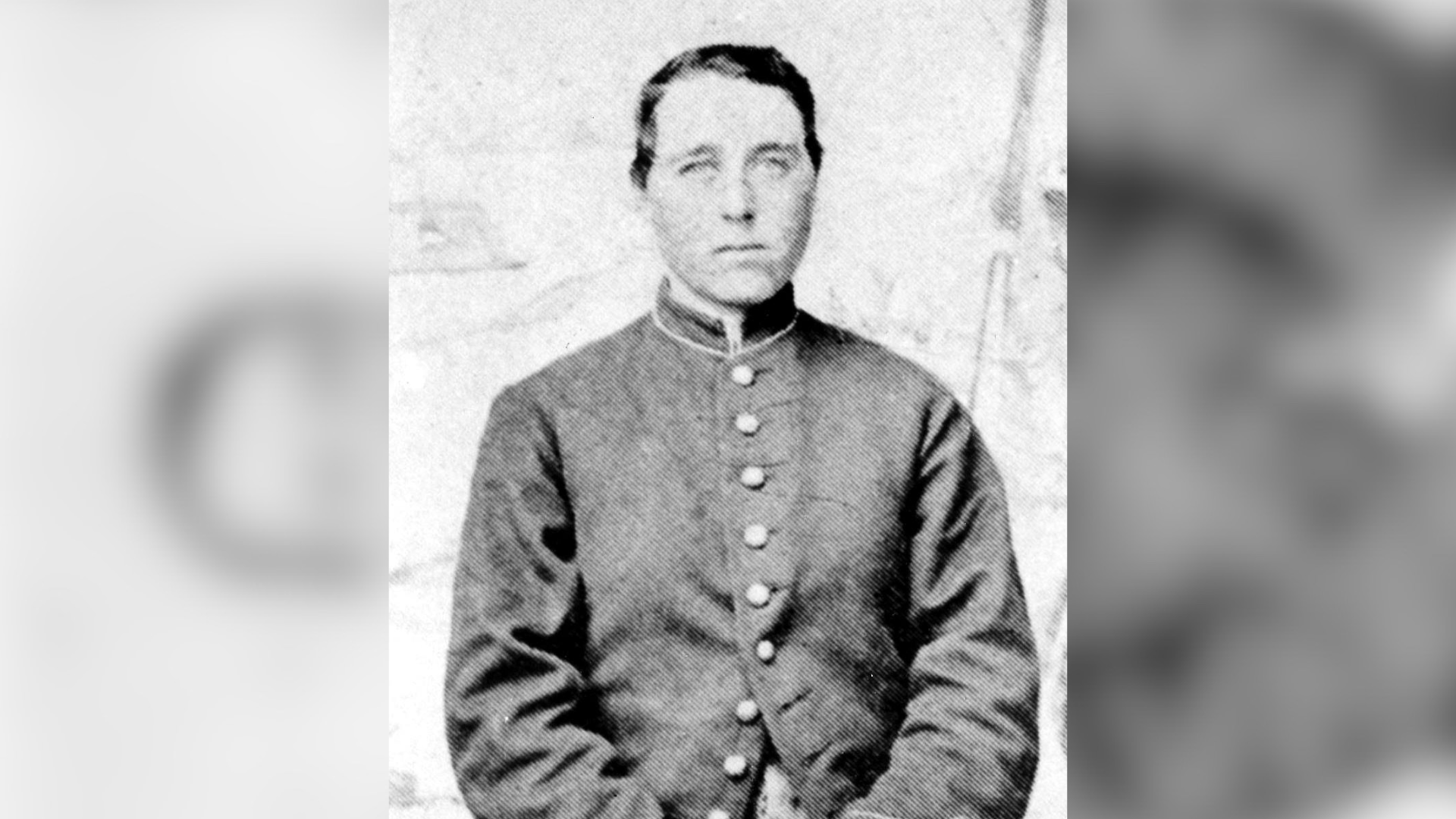

Who was Albert Cashier (Jennie Hodgers)?

Albert Cashier, born Jennie Hodgers, was a remarkable individual who defied societal norms during the American Civil War. In 1862, at the age of 18, they enlisted in the 95th Illinois Infantry as a private.

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Despite being the shortest soldier in the regiment, Albert was accepted by fellow soldiers and proved to be a dedicated fighter. Albert’s regiment participated in over 40 engagements, including the siege of Vicksburg, the Battle of Nashville, and campaigns in Georgia. Post-war, Albert continued to live as a man. Their unwavering commitment to a male identity has led some scholars to consider Albert as a transgender man.

African Americans Didn’t Fight For the Confederate Army

Another rumor that persists today is the idea that African American slaves fought for the Confederate Army — or were forced to. There is no documentation to prove that this ever happened.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

However, many slaves did follow Confederate Armies, as they worked as camp slaves for soldiers. These slaves had the roles of cooks or musicians, while others repaired railroad lines or worked in munitions factories.

Confederate Leaders Didn’t Want African American Soldiers

In January 1864, Confederate General Patrick Cleburne proposed the idea of arming slaves to try to create more troops. This was immediately rejected, and many Confederate leaders were incredibly against the idea.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

However, by March 1865, things had changed. The Confederates agreed to use Black troops in their fight against the Union — only four weeks before the war ended. This move never appeared to even have time to allow slaves to be trained as soldiers.

Abraham Lincoln was Not the Primary Speaker on the Day of the Gettysburg Address

The famous Gettysburg Address was not initially intended as the main speech of the day.

Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

Renowned orator Edward Everett was slated to deliver the primary address, a meticulously prepared two-hour speech. President Lincoln, delivering his concise address afterward, overshadowed Everett’s lengthy oration, reducing it to a historical footnote.

Lincoln Did Not Wing the Gettysburg Address

While Lincoln may not have been the primary attraction, he approached the occasion with due significance. Contrary to popular myth, he did not hastily jot down his speech on the back of an envelope while en route to Pennsylvania.

Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

In reality, he had been meticulously crafting his remarks ever since receiving the invitation. Like the rest of the nation, he had almost five months to reflect on the profound costs of the battle. It is probable, however, that the finishing touches to the Gettysburg Address were applied the night before the ceremony.

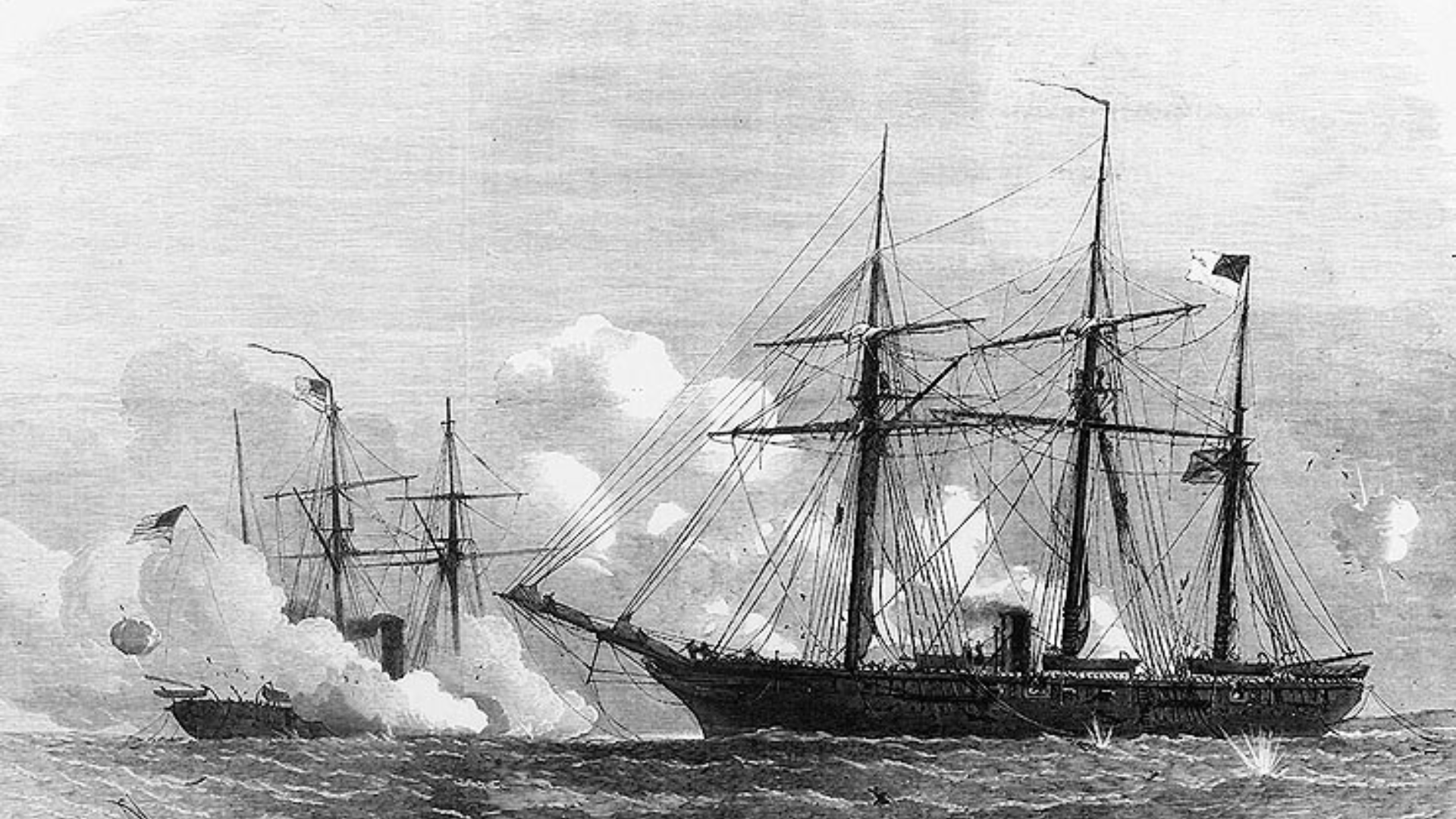

The American Civil War was Only Fought in U.S. Territory

Naval warfare played a significant role in the Civil War, challenging the notion that the conflict was confined to land battles within the U.S.

Illustrated London News/Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Cherbourg off the coast of France in 1864, where the Confederate ship CSS Alabama faced the Union’s USS Kearsarge, exemplifies the war’s international dimension.

The Nuances of the American Civil War

Dispelling these misconceptions reveals the nuanced nature of the American Civil War.

Cornell University Library/Wikimedia Commons

A range of diverse perspectives, challenges, and unexpected moments defined this transformative period in U.S. history. Understanding that conventional narratives gloss over complexities is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of the Civil War’s profound impact on the nation.