Napoleon Abandoned a Group of Scientists in Egypt and They Took the First Steps Towards Modern Archaeology

Napoleon Bonaparte is most known for being one of the most successful generals of all time, and of course, as the emperor of France. But most people don’t realize that he essentially birthed archaeology as we know it today by stranding a group of French scientists in Egypt.

As the story goes, Napoleon brought a group of over 150 scholars to Egypt when he invaded the country. But then, when he returned to France, he left the men behind and they proceeded to examine the ancient world in incredible detail.

Why Napoleon Went to Egypt

According to historical texts, Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798 with 35,000 soldiers in order to disrupt British trade routes from India.

Source: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

The general and his troops quickly took power in Egypt, through force, and by proclaiming to the people of Egypt that he had come to liberate them from Ottoman oppression. He later used his position in Egypt to take the islands of Malta and Crete and retain control of the Mediterranean.

Establishing a “Scientific Enterprise”

When Napoleon first proposed the invasion of Egypt, he explained that he would be defending French trade interests, as well as establishing a “scientific enterprise.”

Source: Stephane Cardinale/Corbis/Getty Images

At that time, many people around Europe had at least heard of the Great Pyramids of Egypt, and many were curious about their structure and the ancient culture of the land.

150 Scholars Made Their Way to Egypt

In order to make good on his promise to conduct research in Egypt, Napoleon brought 150 “savants” who were today’s scholars, scientists, naturalists, and mathematicians on his journey.

Source: The Print Collector/Getty Images

Upon their arrival, Napoleon told them that their mission wasn’t to understand the building of the pyramids, but instead, finding ways to benefit the French invasion.

Finding a Way to Purify the Nile

General Napoleon’s first and most important assignment for the “savants” was to find a way to purify the water in the Nile River.

Source: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Napoleon also wanted them to find out how the Egyptians brewed beer without hops and examine their superior bread ovens. There was no mention of examining historical artifacts or investigating the Great Pyramids.

Napoleon Left the Scholars Behind

However, everything changed when only a year after their arrival, Napoleon left Egypt and returned to France in order to take power and become emperor.

Source: Pixels

And as he departed in such a rush, Napoleon left his 30,000 soldiers and 150 savants he brought with him behind. The scholars stayed in Egypt for the next year until the French troops were forced to retreat, and what they found during that time changed the world forever.

The Scholars Were Not Archaeologists

It’s important to understand that these so-called “savants” were not archaeologists as we know them to be today.

Source: Freepik

In Nina Burleigh’s book “Mirage” about Napoleon’s scholars in Egypt she wrote, “Very few of the scholars were antiquarians, those quintessentially eighteenth-century characters, mostly wealthy, who filled their curiosity cabinets with strange old objects picked up on their travels, barely understanding what they had.”

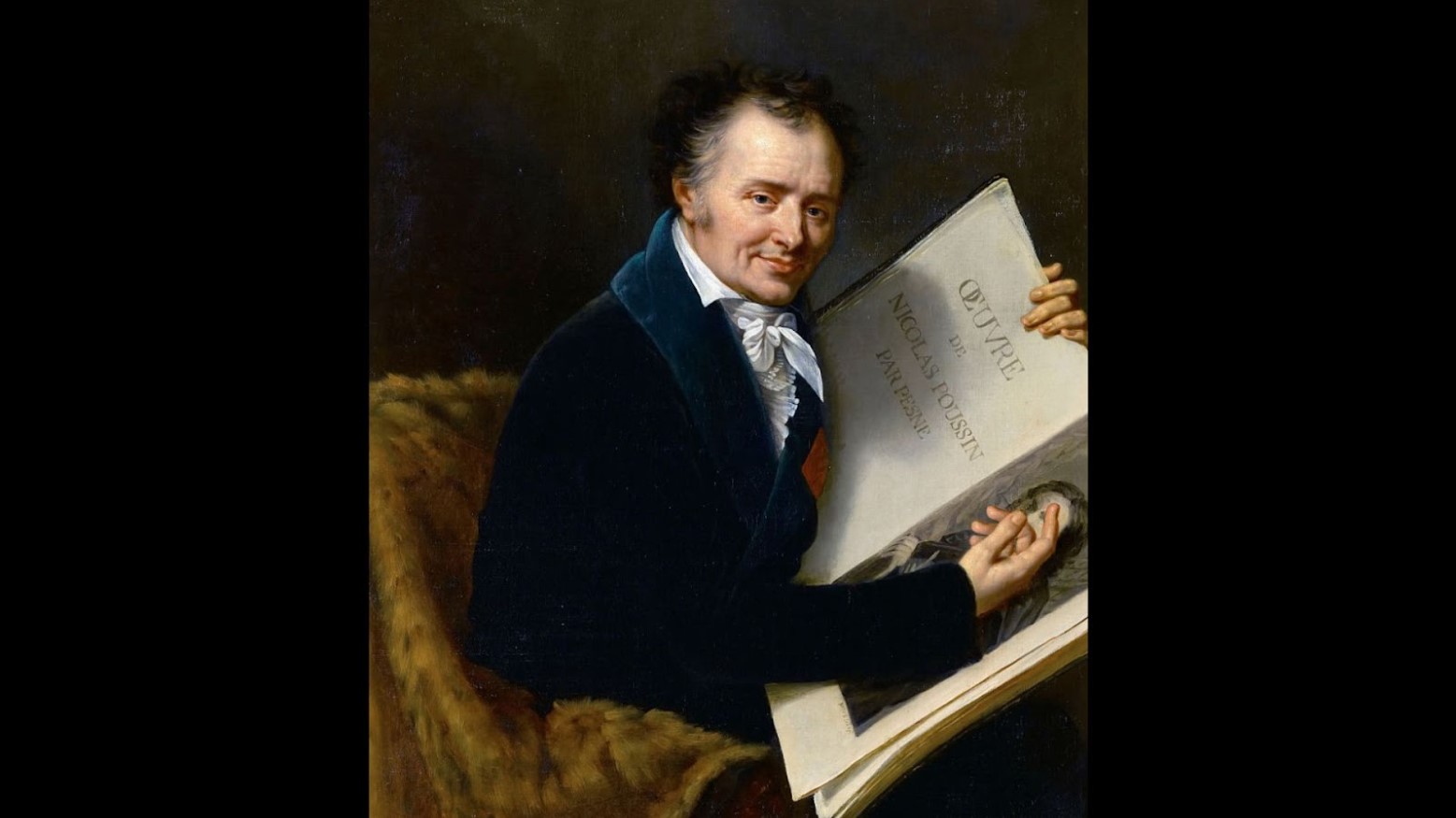

Dominique-Vivant Denon Wrote About the Scholars' Time in Egypt

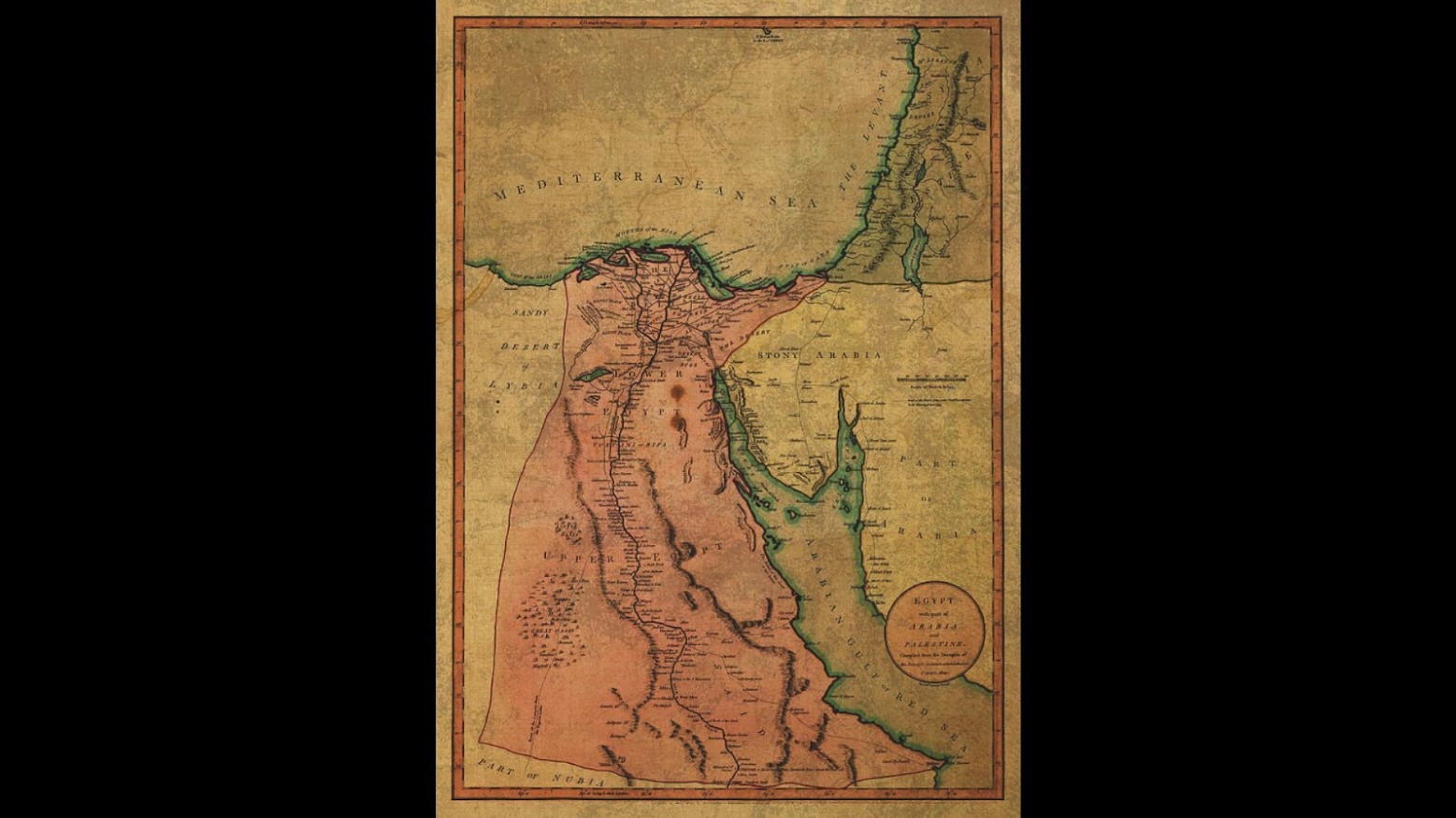

Fortunately for historians, artist and writer Dominique-Vivant Denon was among the scholars in Egypt at the turn of the 19th century, and he wrote detailed accounts of their experience.

Source: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

In fact, upon his return to France, Denon released his book entitled “Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt”, full of maps and detailed drawings of the landscape and ancient structures.

Napoleon’s Savants Published Their Findings

Additionally, when the scholars eventually returned to Europe, they collective published “La Description de l’Egypte,” which was made up of several volumes of essays, engravings, and illustrations of what they found.

Source: Wikipedia

The encyclopedia was extremely popular throughout the continent, and many argue it was this volume of books and their contents that sparked an entire generation’s interest in archaeology.

The World Fell in Love with Egyptology

Because of the detail the scholars used to describe their findings in Egypt and the history behind them, people began looking at ancient artifacts as more than just collectible items.

Source: Fadel Dawod/Getty Images

And, more specifically, academics and even the general population became completely enthralled with the study of ancient Egypt. Consequently, Egyptology was born.

Archaeology Museums Popped Up all over Europe

Because of the new-found love for ancient history, archaeological museums began showing up all over.

Source: Steve Christo/Corbis/Getty Images

And the very first was a museum dedicated solely to the study of Egyptian archaeology at the Louvre in 1827.

“Archaeology as a Science”

There’s really no doubt that Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, and more specifically the 150 scholars he left there, made archaeology far more popular than it had ever been before.

Source: Culture Club/Bridgeman/Getty Images

But even more importantly, Burleigh argues in her book that “Napoleon’s scholars and engineers are remembered most as men who helped found archaeology as a science.”