NASA’s “Tough Decision” to Leave Stranded Astronauts Puts Their Safety First

NASA faced an unexpected challenge when astronauts Butch Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams were left stranded on the International Space Station (ISS) in June 2024. Their return journey was delayed due to propulsion issues with the Boeing Starliner spacecraft.

NASA has had to make tough decisions to ensure their safe return to Earth.

The Boeing Starliner’s Propulsion Problems

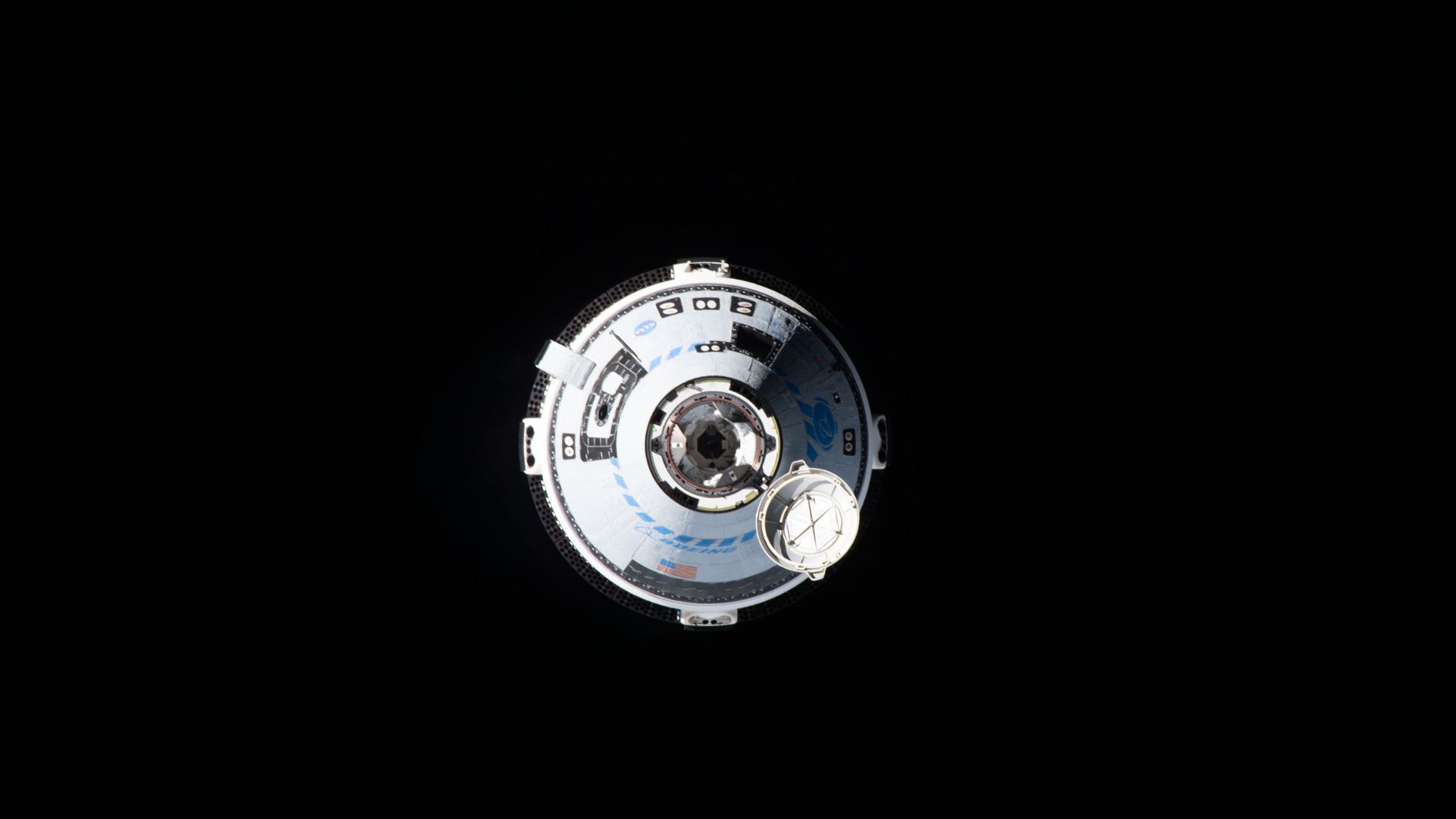

The Boeing Starliner, launched on June 5, 2024, experienced several critical failures. Five maneuvering thrusters stalled, and multiple helium leaks were detected, alongside a faulty propellant valve.

Source: Bob Hines/NASA/Wikimedia Commons

These issues made the spacecraft too dangerous for the crew’s return journey, leading NASA to conclude that Starliner should return uncrewed to Earth.

A New Plan Emerges

In light of the Starliner’s malfunctions, NASA devised a new plan. It was decided that astronauts Wilmore and Williams would return home aboard the SpaceX Crew-9 mission instead.

Source: Picryl

This shift required careful coordination and resulted in reshuffling the Crew-9 lineup.

The Decision to Downsize Crew-9

To accommodate Wilmore and Williams on the SpaceX Crew-9 mission, NASA made the difficult decision to reduce the Crew-9 team from four to two members.

Source: Joel Kowsky/NASA via Getty Images

Initially set to launch with four astronauts, the Crew-9 mission now features only Nick Hague and Aleksandr Gorbunov, each with crucial roles in ensuring mission success.

Boeing Puts Safety First

While Boeing did not have a representative to talk on behalf of the company at NASA’s news conference, the company did issue a statement.

Source: Wikimedia

“We continue to focus, first and foremost, on the safety of the crew and spacecraft. We are executing the mission as determined by NASA, and we are preparing the spacecraft for a safe and successful uncrewed return,” the statement read.

Boeing’s Ongoing Setbacks

The return of Boeing’s empty Starliner is another hurdle in a decade filled with difficulties for the company. In 2014, NASA selected both Boeing and SpaceX to create spacecraft capable of transporting astronauts to and from the ISS.

Source: Andrea Piacquadio/Pexels

After NASA retired its shuttle fleet in 2011, marking a decade of continuous human presence on the station, the agency had to rely on Russia for astronaut transportation, a position it was eager to change.

Balancing Experience and Safety

NASA Chief Astronaut Joe Acaba, based at the Johnson Space Center, made the call to select Nick Hague to command the Crew-9 mission.

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

With over 200 days in space and multiple missions under his belt, Hague’s experience was vital in maintaining an integrated crew capable of safe station operations alongside Roscosmos cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov.

The Challenges of Reshuffling Crews

Zena Cardman and Stephanie Wilson, who were originally slated for the Crew-9 mission, were reassigned. This decision, while challenging, was necessary to ensure the safe return of Wilmore and Williams.

Source: NASA/Joel Kowsky/Wikimedia Commons

Both Cardman and Wilson remain dedicated to their future missions.

Nick Hague: A Seasoned Veteran

Nick Hague, an astronaut with 203 days logged in space, is no stranger to challenges. In 2018, he survived a rocket booster failure during his first launch, leading to a dramatic in-flight abort and safe landing.

Source: Bob Hines/NASA/Wikimedia Commons

His experience and calm under pressure make him a fitting commander for the Crew-9 mission amidst these unexpected changes.

Aleksandr Gorbunov: The First Mission

For cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov, Crew-9 will mark his first trip to space. An engineer with a strong background in spacecraft and upper stage operations, Gorbunov’s skills will be crucial for maintaining the ISS’s systems.

Source: NASA/Joel Kowsky/Wikimedia Commons

His debut adds a layer of intrigue to the mission, as he joins seasoned veterans on a high-stakes journey.

A Long Summer for the Astronauts

“It’s been a long summer for our team,” said Steve Stich, the manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, who said that the situation with the thrusters was too complicated to know whether or not they might fail at a critical time. “There was just too much uncertainty in the prediction of the thrusters.”

Source: Aubrey Gemignani/NASA via Getty Images; NASA/Wikimedia Commons

“Space flight is risky, even at its safest and even at its most routine. And a test flight, by nature, is neither safe nor routine,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said at a press briefing.

Excitement in the Face of Adversity

While the hard work and inconvenience of the extended stay might have lasting effects on Wilmore’s and Williams’s bodies, the excitement of life in orbit is one that these astronauts spent their lives working toward.

Source: Wikimedia

“I know them really well, and in a way, I think they were a little disappointed to fly in space with such a short amount of time,” said Fossum. “They both also have done long-duration missions on the space station before… and they both loved it.”

Another Astronaut Who Got Stuck in Space Speaks Out

Wilmore and Williams are not alone in their experience. Frank Rubio, who holds the record as the longest astronaut in space after his visit to the ISS lasted just over a year ago, has been helping out his friends up in space.

Source: Freepik

“They’re doing great work, really maintaining a positive attitude up there, setting a great example and knocking out a whole lot of extra work on the space station,” Rubio told The Associated Press from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Part of the Job

While the astronauts will not return until next year, Rubio said that “they’ve done a fantastic job of dealing with adversity.”

Source: Cytonn Photography/Pexels

While their families have had to make sacrifices because of the switch in plans, they understand “that’s part of our job is just to adapt and overcome and make the best of the situation,” he said, “and they’ve done just that, so super proud of them.”

Preparing for a Complex Return Journey

Wilmore and Williams will stay aboard the ISS until February 2025, when they will return to Earth on the Crew-9 Dragon capsule.

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

This extended stay means more time for scientific research and maintenance tasks, keeping the crew busy while they await their return trip.

Confidence in the Crew

Despite the challenges, NASA’s confidence in the Crew-9 members is unwavering. “I have the utmost confidence in all our crew,” said Joe Acaba.

Source: Joel Kowsky/NASA via Getty Images

This sentiment is echoed by Zena Cardman and Stephanie Wilson, who expressed their support for Hague and Gorbunov, highlighting the camaraderie and professionalism among the astronauts.

The Two Astronauts Sitting Out

Although Cardman and Wilson will sit this spaceflight out, NASA agency officials stated that these astronauts “are eligible for reassignment on a future mission.”

Source: Freepik

Crew-9 would have been Cardman’s first mission and Wilson’s fourth, following space shuttle missions STS-121 in 2006, STS-120 in 2007, and STS-131 in 2010.

The Reason Cardmand and Wilson Are Sitting Out

NASA spacecraft generally fly with at least one US military pilot aboard. However, the reassigned astronauts from Crew-9, Cardman and Wilson, are a scientist and an engineer by training, respectively.

Source: DC Studio, Freepik

Hague and Ovchinin successfully arrived at the ISS in 2019. This upcoming mission to retrieve the astronauts stuck in space will be a testament to the talents of these experienced astronauts.

Looking Ahead to Future Missions

While Cardman and Wilson won’t be flying on Crew-9, they remain part of NASA’s future mission plans.

Source: Wikimedia

Their reassignment shows NASA’s strategic approach to crew assignments, ensuring that all astronauts have opportunities to contribute to ongoing and future space exploration endeavors.

NASA Is Not In Crisis

While Boeing’s Starliner was a setback for Boeing, the US space program is not suffering a setback from the company’s failures because NASA planned.

Source: Ethan Miller/Getty Images

“Commercial Crew purposefully chose two providers for redundancy in case of exactly this kind of situation,” Laura Forczyk, an independent consultant in the space industry, said to New Scientist.

NASA’s Backup Plan

As mentioned earlier, NASA is working with Boeing and SpaceX. While Boeing has faced significant setbacks with their one rocket, SpaceX has launched multiple tests in the last few years in preparation for its first manned mission.

Source: Wikimedia

“If they had only selected one provider, it would have been Boeing, because SpaceX was the risky prospect at the time,” says Forczyk. “So in a way, this is a triumph of the Commercial Crew Program.”

This Trip Was a Test for Boeing

“This was a test mission, but sometimes in tests, the answer is, you’ve got something you need to fix,” said retired NASA astronaut Michael Fossum in a statement. “Tests don’t always prove that everything worked perfectly.”

Source: Wikimedia

NASA administrator Bill Nelson stated that the Starliner will get another chance to fly a crew to the ISS, but future missions rely on the performance of the next (and possibly final) space mission for Boeing.

One Last Chance

Boeing’s contract with NASA states that the craft cannot be certified for real missions until it has had a successful test flight—which this current test has not been. If the Starliner does another test flight, it could push the first operational flight back to 2026 as soon as possible.

Source: Benjamin L. Granucci

The Starliner also faces pressure, as plans to deorbit the ISS and send it into space are set for around 2030.

A Nod to Resilience

The decisions surrounding Crew-9 and the rescue of Wilmore and Williams reflect the resilience and determination of NASA and its international partners.

Source: NASA/Bill Ingalls/Wikimedia Commons

As space exploration pushes the boundaries of human capability, it’s this resilience and determination that will continue to drive NASA’s future forward.