New Discovery Indicates Humans Were in Europe Much Earlier Than We Thought

Recent studies published in Nature and Nature Ecology and Evolution have revealed ancient human bones in a northern German cave, indicating that humans inhabited Europe much earlier than previously believed.

The findings suggest that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals coexisted in Europe for thousands of years. This discovery shifts the timeline of human expansion into northern Europe back to 45,000 years ago, challenging prior assumptions about the earliest human presence in the region.

Earliest Homo Sapiens in Europe

The Hill reports that Elena Zavala, a co-author of the Nature paper and a research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, said, “These are among the earliest Homo sapiens in Europe.”

Source: Tim Schüler TLDA/Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

This revelation pushes back the confirmed presence of Homo sapiens in northern Europe by several millennia, providing a new perspective on the timeline of human migration and settlement across the continent.

Coexistence of Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals

CBS News reports that Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist leading the new research, told AFP about a “replacement phenomenon” that occurred between the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic periods when both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals existed in Europe.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

This period’s archaeological evidence, including stone tools from both species, has been difficult to accurately attribute due to a lack of bones.

Impact on Neanderthals

The studies suggest a darker aspect of human history, proposing that the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe contributed to the decline and eventual extinction of Neanderthals after their 500,000-year dominion, CNN reports.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

This hypothesis is supported by genomic research indicating that Homo sapiens were the sole survivors of this period, carrying genetic traces of Neanderthals due to past interactions.

The Neanderthal Extinction Mystery

The exact cause of Neanderthal extinction remains a subject of speculation among scientists.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Some theories suggest that humans played a role in their demise through violence, disease transmission, or competition for resources, while others propose that interbreeding contributed to the dilution of Neanderthal characteristics within the human gene pool, per information from CBS News.

Reevaluation of European Settlement History

Tim Schüler, involved in historical preservation for the German state of Thuringia, said to The Hill that finds from the Ranis site have “fundamentally changed our ideas about the chronology and settlement history of Europe north of the Alps.”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

These findings challenge previous notions about the timeline and nature of human settlement in the region, indicating a more complex history than was understood.

The Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician Culture

CBS News reveals that tools belonging to the “Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician”(LRJ) culture have been found at various sites north of the Alps, including in England and Poland. Determining who made these tools has been challenging.

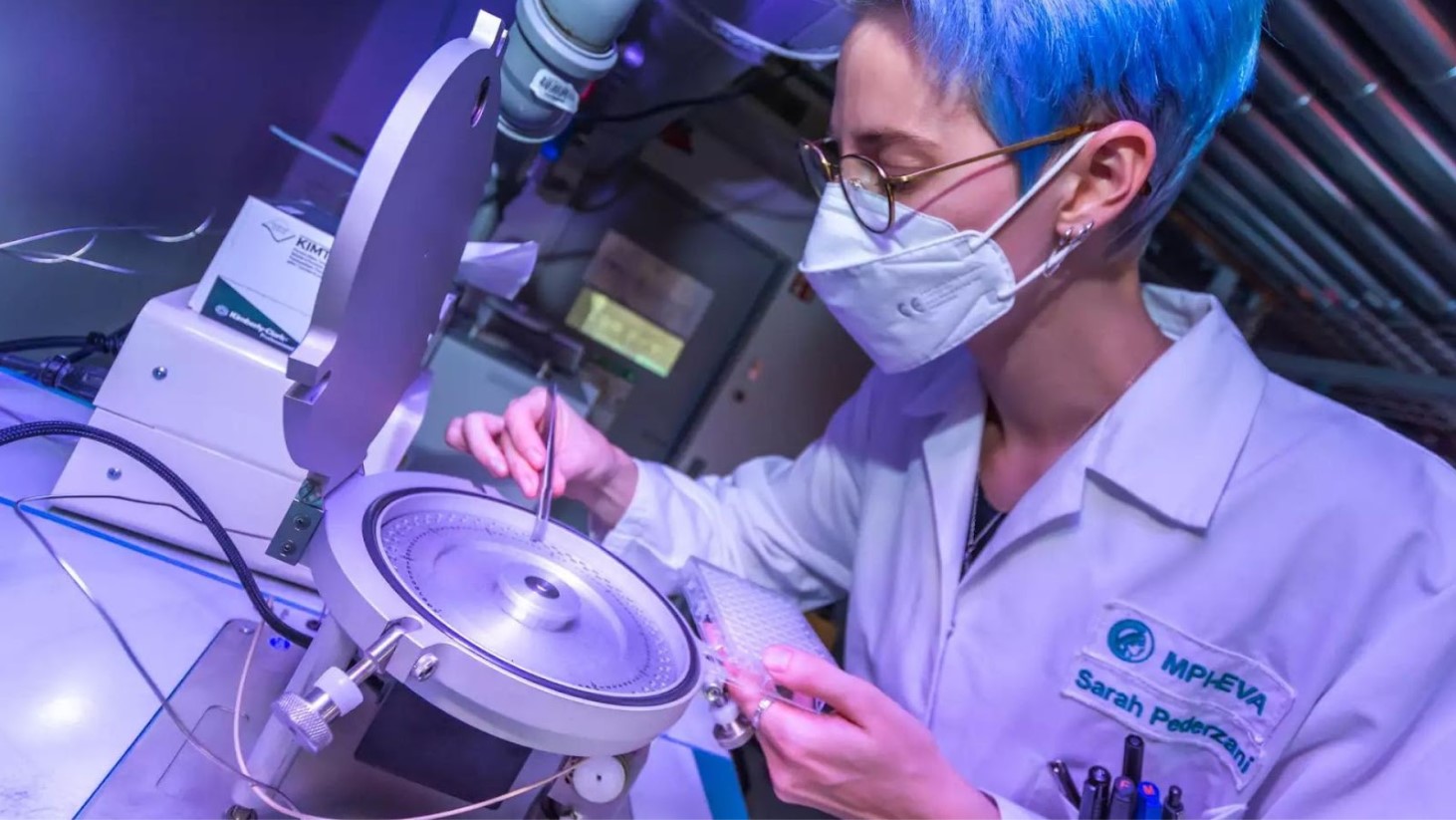

Source: Tim Schüler TLDA/Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

The recent excavation near the town of Ranis in central Germany aimed to provide more clarity, focusing on the study published in the journal Nature.

Exploring Ancient Human Migration

The authors of the study suggest that the cave was a resting place for small pioneer groups of modern humans pushing into the colder regions north of the Alps.

Source: Marcel Weiss /Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

CNN notes that this challenges the idea that Neanderthals were the sole inhabitants of Europe during this time and provides evidence of early human adaptation and migration into less hospitable climates.

Adapting to Harsh Climates

The researchers noted that the early human groups who moved into northern Europe faced conditions much colder than today, similar to modern-day Siberia or northern Scandinavia.

Source: Roman Purtov/Unsplash

These groups lived in small, mobile communities, relying on the meat of reindeer, woolly rhinoceroses, horses, and other animals for sustenance, CBS News reports.

Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

Due to the small size of the bone fragments found, researchers could not extract intact nuclear DNA. Instead, they sequenced mitochondrial DNA, which traces the maternal line.

Source: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

This analysis revealed that many bone fragments came from relatives of people whose remains had previously been identified, offering new insights into the familial relationships and movements of early Homo sapiens, via CNN.

Discovery of Long-Lost Relatives

CNN reveals that the mitochondrial DNA analysis linked 12 of the 13 individuals found at Ranis to a 43,000-year-old skull of a woman discovered in a cave in what is now the Czech Republic, suggesting they were long-lost relatives.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The discovery of this connection across time provides a unique glimpse into the lives and relationships of ancient humans.

Rewriting the History of Human Craftsmanship

CBS News reports that the realization that humans, not Neanderthals, created the stone tools found in the cave was described as “a huge surprise” by study co-author Marcel Weiss.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

By providing concrete evidence of early human presence and technological prowess, the research from the Ranis cave offers a new perspective on the narrative of when Homo sapiens first left Africa for Europe and Asia, suggesting a more gradual and earlier migration into Europe than previously thought.