New Findings Suggest the Moon Was Once Engulfed by a Magma Ocean

Scientists recently uncovered evidence suggesting that the moon was once covered by a vast ocean of molten rock. This revelation comes from the Chandrayaan-3 mission, which analyzed lunar soil from the moon’s south pole, a region that had never been explored before.

The findings offer a new perspective on the moon’s fiery origins, dating back over 4 billion years.

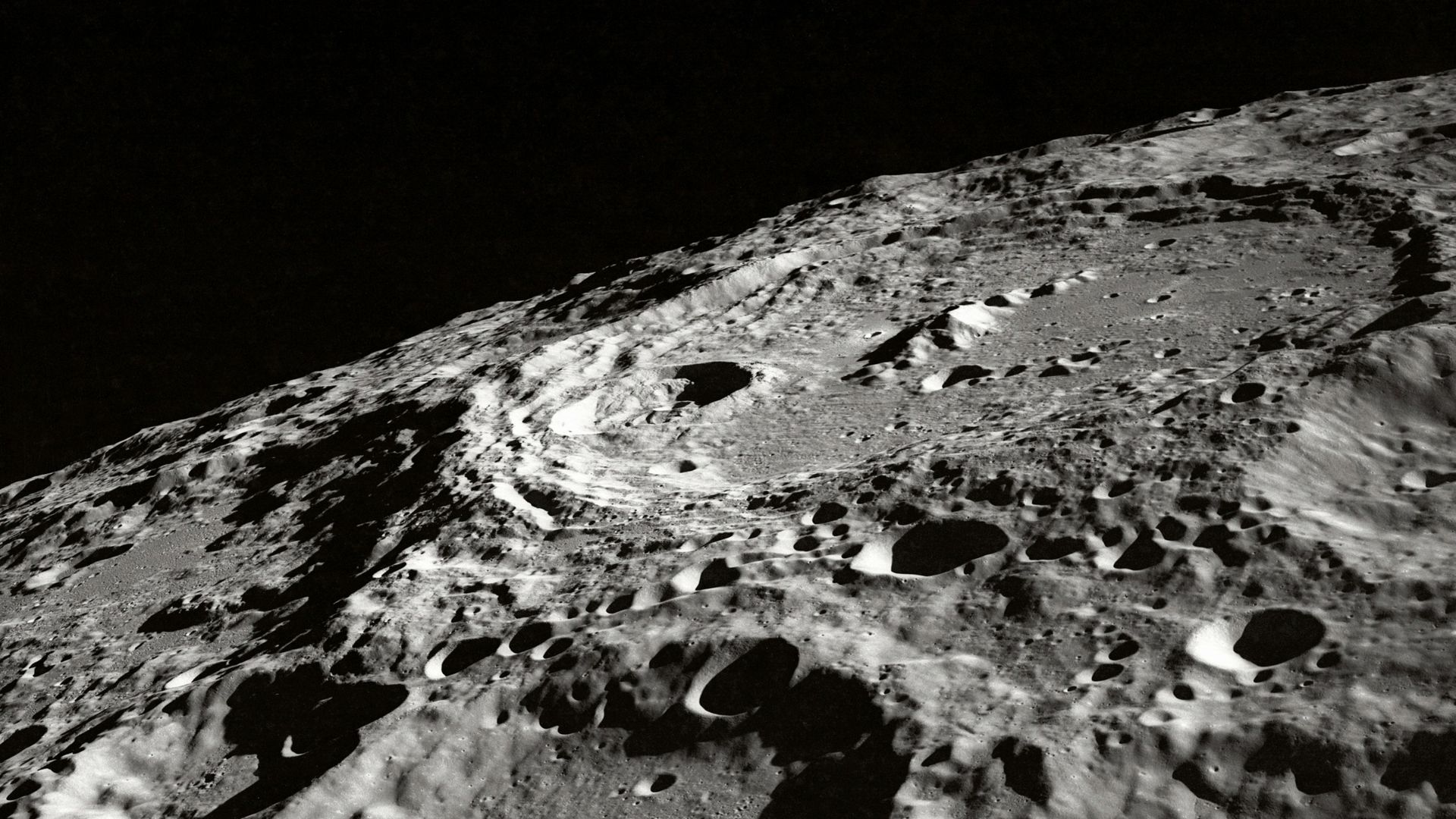

Chandrayaan-3's Historic Landing

In August 2023, India’s Vikram lander made history by touching down further south than any previous lunar mission. This challenging landing near the moon’s south pole provided scientists with a unique opportunity to study untouched lunar soil.

Source: NASA/Unsplash

The mission’s groundbreaking technology allowed for unprecedented close-up analysis of the moon’s surface.

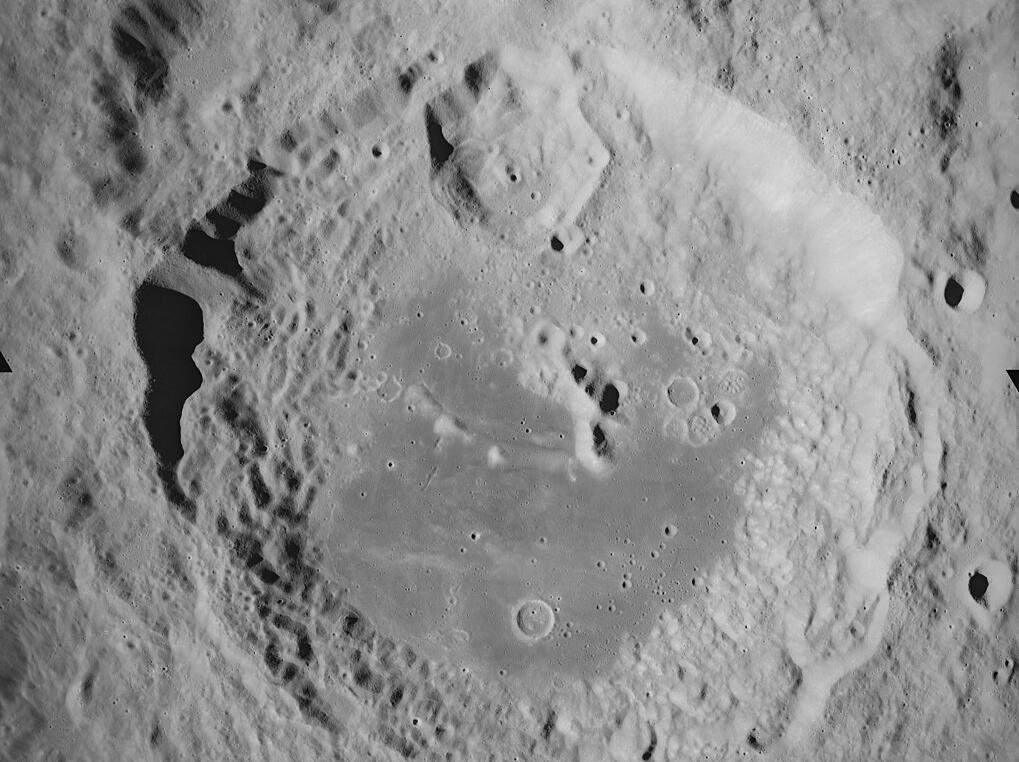

The Hidden Secrets of Lunar Soil

Lunar soil samples collected by Chandrayaan-3 revealed an unexpected uniformity in their composition.

Source: Wikimedia

These samples were primarily made up of a white rock known as ferroan anorthosite, which is linked to the remnants of an ancient magma ocean.

A Closer Look at Ferroan Anorthosite

Ferroan anorthosite, a type of rock found in the lunar soil, points to a time when the moon’s surface was covered in molten rock.

Source: NASA

As the magma ocean cooled, lighter minerals like ferroan anorthosite floated to the surface, forming the moon’s initial crust.

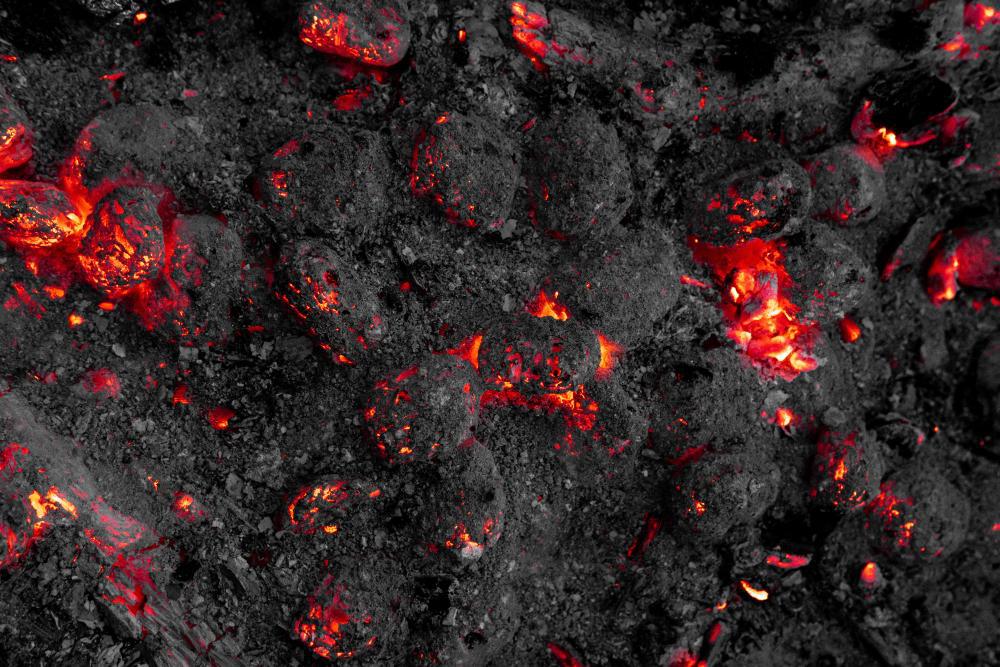

The Moon's Violent Birth

The moon is believed to have formed about 4.24 billion years ago from debris created when a Mars-sized body collided with Earth. The immense heat from this impact likely created a global magma ocean on the moon.

Source: Freepik

This period of molten rock persisted for tens to hundreds of millions of years, shaping the moon’s early landscape.

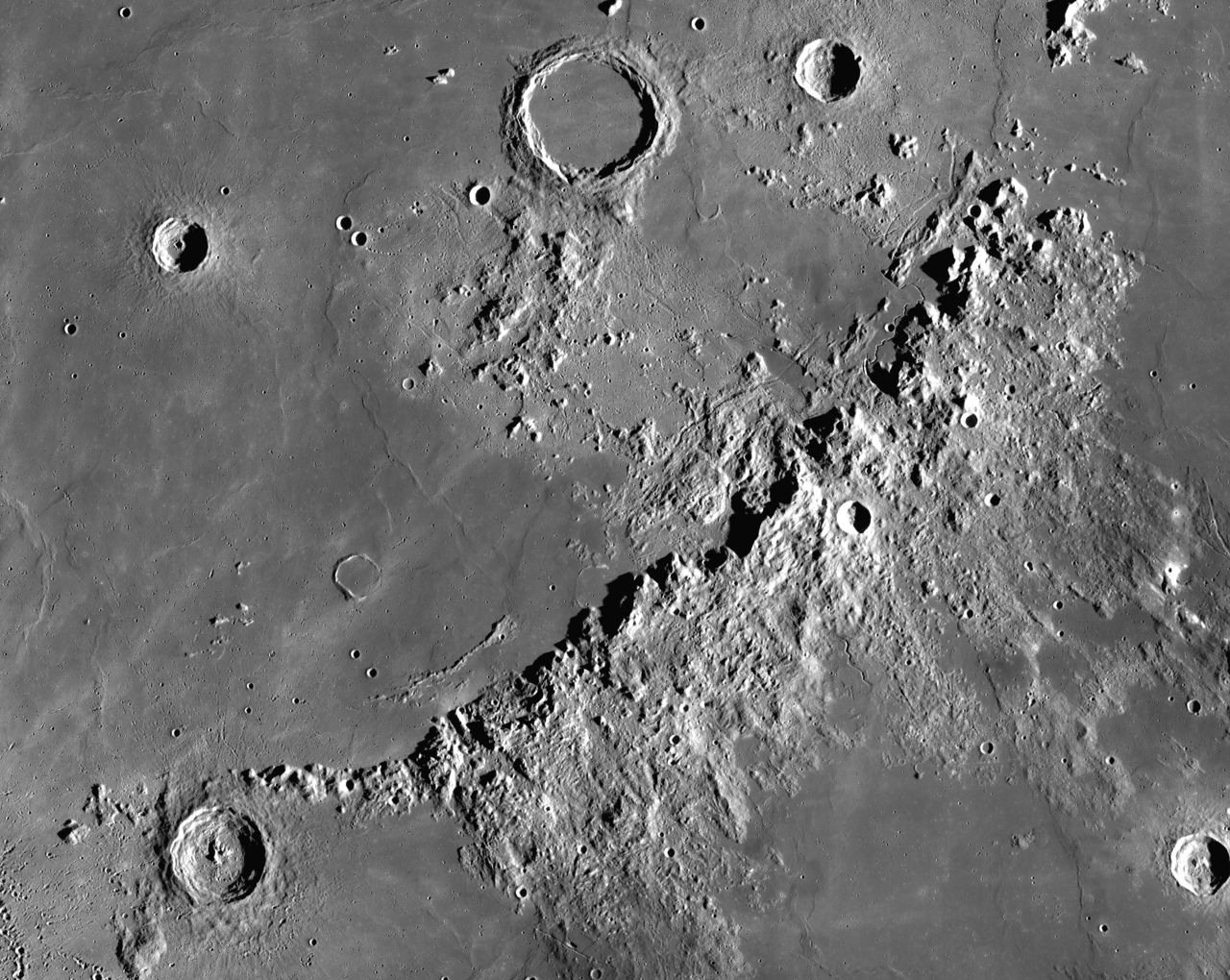

Comparing Lunar Regions

Previous lunar missions, such as Apollo 16 and Luna 20, collected samples from different regions of the moon. These samples showed broad similarities in chemical composition despite being from distant locations.

Source: Wikimedia

The consistency in these findings supports the theory that a single magma ocean once enveloped the moon, providing new insights into its ancient past.

Unraveling the Mystery of the Lunar Highlands

The lunar highlands, where Chandrayaan-3 and other missions have landed, are believed to represent the ancient lunar crust formed from the cooling magma ocean.

Source: Freepik

Researchers have long speculated about the composition of these highlands, and recent findings suggest a more complex geological history than previously thought, involving multiple layers and impact mixing.

The Role of Impact Cratering in Lunar History

Over billions of years, the moon’s surface has been shaped by numerous impact events. These impacts mixed different layers of rock, creating a diverse chemical composition.

Source: NASA/Newsmaker/Getty Images

The Chandrayaan-3 mission’s findings indicate that the moon’s surface at the south pole was likely covered by debris from the South Pole-Aitken basin, one of the largest impact craters in the solar system.

Challenging Previous Moon Models

The new data challenges earlier models of the moon’s formation, which suggested a simpler structure.

Source: Toby Elliott/Unsplash

Instead, the presence of more magnesium-rich rocks alongside ferroan anorthosite suggests a more layered and dynamic history.

Implications for Future Lunar Exploration

The discovery of a once-magma-filled ocean on the moon has significant implications for future exploration. Researchers are eager to explore other regions, particularly the permanently shadowed areas near the poles, which could contain water ice.

Source: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Understanding these regions could provide crucial resources for future lunar missions and human exploration.

The Continuing Quest

The findings from Chandrayaan-3 are just the beginning. Scientists plan to build on this research with future missions to uncover more secrets about the moon’s past.

Source: NASA/Interim Archives/Getty Images

These discoveries are crucial for understanding not only the moon’s history but also the broader processes that govern planetary formation and evolution in our solar system.

A New Chapter in Lunar Science

As researchers continue to analyze the data from Chandrayaan-3, the moon’s history becomes clearer.

Source: Wikimedia

The evidence of a long-lost magma ocean opens a new chapter in our understanding of the moon’s geological evolution.