Over Half a Century Ago, the Vatican Played a Huge Role in the Science Behind IVF

Amid the Catholic Church continuing to officially oppose in vitro fertilization (IVF), light has been shed on how the Vatican played a massive role in helping to push the science behind IVF.

In the late 1950s, many men of science began to work with the Vatican and its associates as they tried to help infertile women. This partnership eventually led to a huge breakthrough in IVF.

Bruno Lunenfeld’s Work

In 1957, scientist and endocrinologist Bruno Lunenfeld traveled to Rome to give a presentation to the board of Istituto Farmacologico Serono, a pharmaceutical company.

Source: Caleb Miller/Unsplash

His presentation was made to convince the board to help him develop a therapy that he had been working on for four years. This therapy was to help induce ovulation in women who were struggling with infertility, yet wanted to have children.

The Beginning of a Partnership

Unfortunately, for Lunenfeld, the board didn’t agree to work with him. According to many of these board members, what Lunenfeld was asking for was too difficult — even though their own staff scientist Piero Donini was also working on this infertility issue.

Source: Karim Ben Van/Unsplash

Lunenfeld left the meeting completely dejected. However, things changed when one of the board members, Don Giulio Pacelli, walked up to him and said he thought he could help.

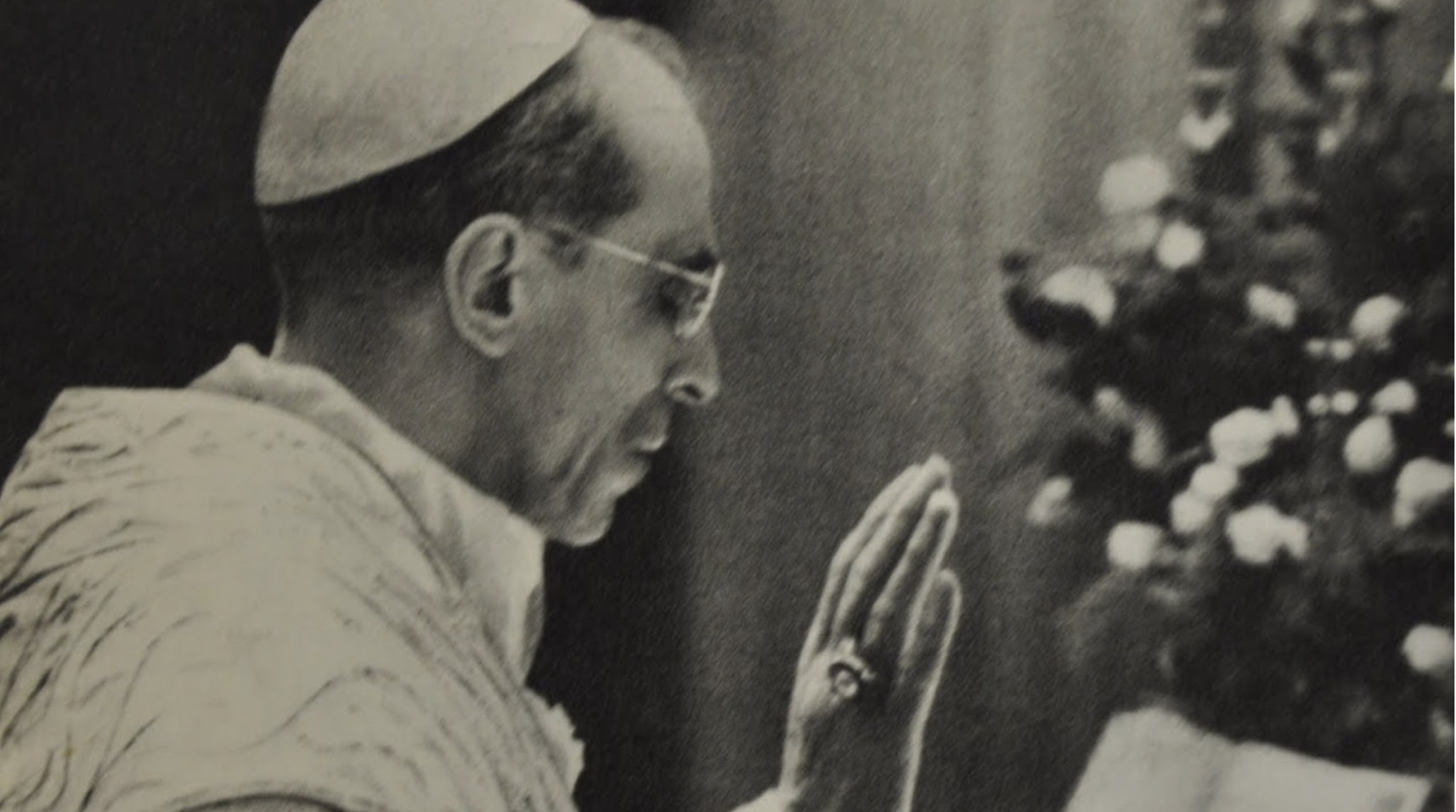

Don Giulio Pacelli

When Lunenfeld first met Pacelli, he wasn’t aware of the influential man that he was agreeing to work with at first. He clearly didn’t know the close ties that Pacelli had to the Vatican.

Source: True Restoration/Wikimedia Commons

At that time, the current pope was Pope Pius XII — Pacelli’s uncle. Through the pope, Pacelli was able to better himself in business throughout Italy, as well as have influence over the Vatican’s doings.

Lunenfeld’s Science

Before Lunenfeld met Pacelli, he was working on trying to help women suffering from infertility. About thirty years before Lunenfeld began to work on this issue, scientists discovered that gonadotropins, peptide hormones, could stimulate ovulation in human women through injection.

Source: Fabio Fistarol/Unsplash

These gonadotropins were extracted from the blood of pregnant horses. However, Lunenfeld discovered that another hormone could be used to successfully help infertile women: human urine.

Purifying Human Waste

Specifically, menopausal urine could help infertile women. One of the main issues with gonadotropins from horses was they formed antibodies that neutralized in women. Hormones obtained through women did not have this.

Source: Sean Ang/Unsplash

Through this menopausal urine, scientists were able to obtain human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG), which contained FSH and LH, and therefore didn’t have any side effects. For purification, this urine was mixed with activated kaolin clay.

What Lunenfeld Needed

Once Lunenfeld discovered the purification process of urine, he realized that he needed mass amounts of urine from menopausal or postmenopausal women. However, he also needed to ensure none of this urine was from pregnant women, as that would ruin the entire batch he was collecting.

Source: Vonecia Carswell/Unsplash

At his meeting with the board members in 1957, it was this collection of urine that made them decide against helping Lunenfeld. They believed it couldn’t be done in this massive way. However, Pacelli differed in opinion.

Using Nuns

Through this partnership and Pacelli’s close ties with the Vatican, he and Lunenfeld decided to use the urine of nuns. There would be no worry that any of these women were pregnant, so they could safely assume that the urine collected would be free of error.

Source: Gary Bembridge/Wikimedia Commons

According to Lunenfeld, the first year of this experiment saw the urine collection of 100 nuns. These nuns produced about 30,000 liters of urine for them.

The First Year of Collection

Lunenfeld himself explained how this urine greatly helped infertile women in this first year.

Source: Anila amataj/Wikimedia Commons

Lunenfeld said, “We had a hundred nuns recruited, which gave us 30,000 liters, and the 30,000 liters gave us a hundred milligrams of the substance which we needed. And this was enough to make 9,000 vials of 75 units, sufficient for 450 ovulation induction cycles.”

The First Trials

By 1959, the first trials on infertile women could begin, as enough hMG had been harvested by Serono, who had officially decided to help Lunenfeld and Pacelli.

Source: Iopensa/Wikimedia Commons

In 1962, the first previously infertile woman was able to give birth to a healthy baby after being treated with hMG. Though two other women became pregnant but miscarried, this huge success allowed the registering of this compound as Pergonal.

The Vatican’s Anti-IVF Position

This secret history of how the Vatican seemingly allowed its nuns to provide urine that went on to help women using IVF treatment is interesting in light of its current anti-IVF position.

Source: Ashwin Vaswani/Unsplash

In 2024, Pope Francis again reiterated what the Church has long stated: the Vatican is anti-IVF.

The Nuns Who Helped

Unfortunately, there isn’t any paperwork at all about the nuns who gave their urine in massive amounts to scientists to help other women with their infertility. The Vatican has no paperwork on it in its archives, and many of these companies have stated they have lost much of these papers to time.

Source: Monica Domeniconi/Wikimedia Commons

Many nuns likely never talked about giving their urine for scientific purposes, as nuns during this time were not known to publicly talk about situations like this. But one thing is certain: they had the Pope’s blessing. When Pacelli took the idea back to the Serono board, he told them, “The pope is interested.”