Scientist Claims Humans Were Meant to Live Longer, But The Dinosaurs Ruined It

A researcher from the United Kingdom believes he has unearthed compelling evidence that humans’ genetic makeup once permitted our species to live much longer.

However, the influence of ancient dinosaurs dramatically altered this potential — a discovery that could revolutionize our understanding of evolutionary biology.

The Mind Behind the Theory

João Pedro de Magalhães, a distinguished biologist, is the mastermind behind this groundbreaking theory.

Source: Freepik

His theory posits that the dominance of dinosaurs forced all mammals to accelerate their reproductive cycles, leading to the loss of crucial longevity genes.

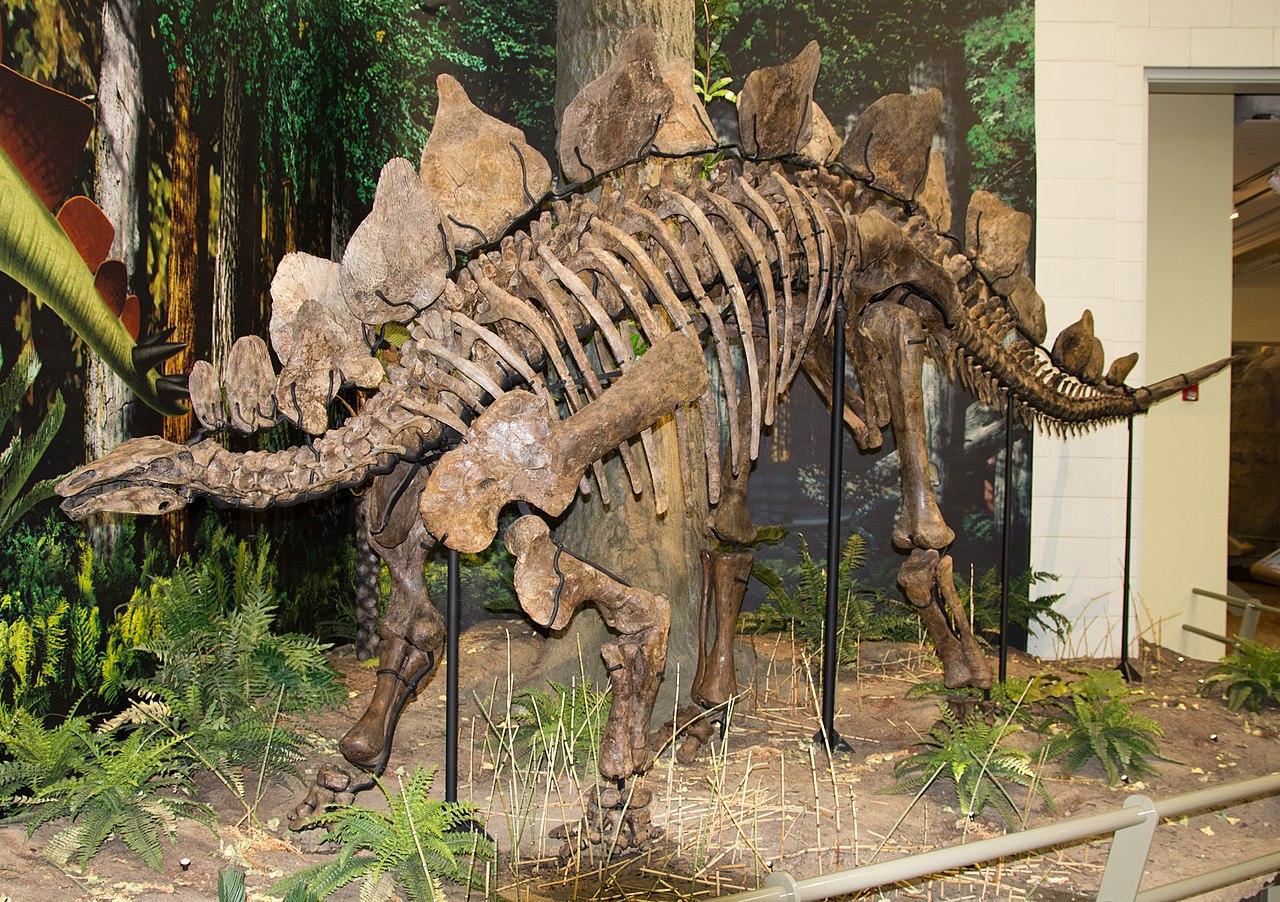

Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth for Millions of Years

Due to their immense size, dinosaurs ruled the Earth for over 150 million years during the Mesozoic era. However, they also had several special traits, including warm blood and the ability to thrive in varied habits, which gave them an advantage over other animals.

Source: Wikimedia

Due to their extended period of dominance, other animals had to adapt to survive the reign of dinosaurs. One such grouping was mammals, from which humans would later originate. Despite having relatively robust longevity genes, de Magalhães explains that mammals’ potential life spans were affected by the constant threat of dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs Lowered Human Lifespan Says Microbiologist

De Magalhães, a microbiologist at the University of Birmingham, developed the “longevity bottleneck hypothesis,” which suggests ancient mammals evolved away from longevity to ensure their species could survive amidst dinosaurs.

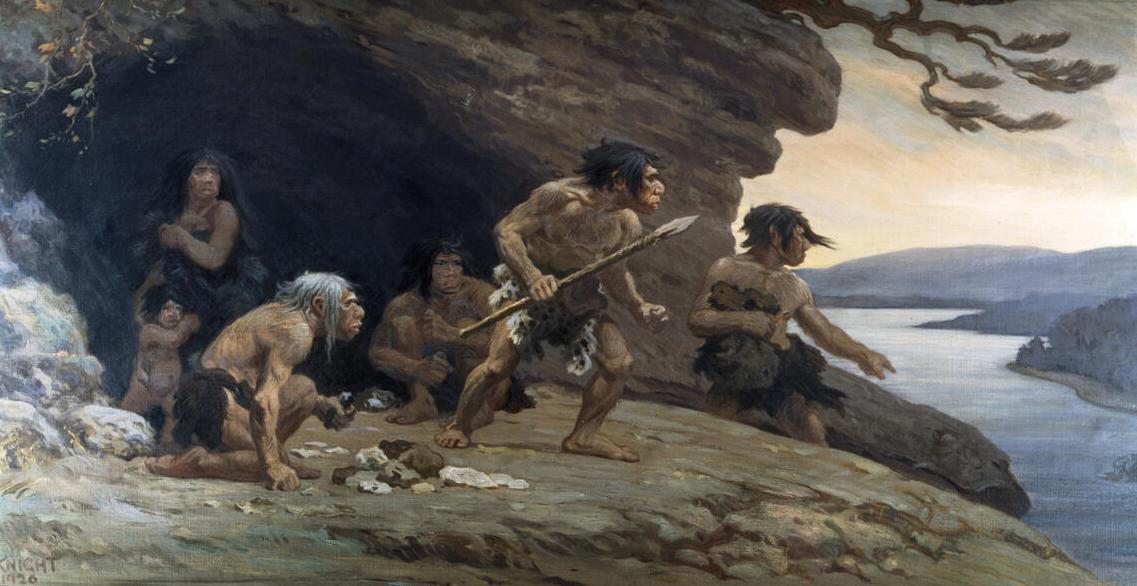

Source: Wikimedia

In his study, the researcher explains the evolutionary track of most mammals living on Earth decided to refocus their efforts on rapid reproduction as opposed to longevity to ensure the species survived.

Mammals Sacrifice Key Longevity Genes

During the Mesozoic period, the constant threat of being prey to dinosaurs forced most mammals to accelerate their reproductive cycles. This led to the unfortunate loss of key longevity genes, showcasing a significant consequence of evolutionary pressure.

Source: Wikimedia

In his theory, de Magalhães suggests that while mammals such as humans can have relatively long life spans, we are still living under dinosaur-era restraints.

Biologist Speaks on His Theory

Speaking on his theory in a paper published in BioEssays, de Magalhães wrote, “My hypothesis is that such a long evolutionary pressure on early mammals for rapid reproduction led to the loss or inactivation of genes and pathways associated with long life.”

Source: Freepik

He continued, “I call this the ‘longevity bottleneck hypothesis,’ which is further supported by the absence in mammals of regenerative traits.”

All Mammals Living Under Dinosaur Era Restraints

De Magalhães admits in his study that elephants, whales and humans have the potential to live fairly long lives when compared to other mammals. However, the evolution of mammals during the Mesozoic era reduced our potential longevity.

Source: Wikimedia

“Evolving during the rule of the dinosaurs left a lasting legacy in mammals,” de Magalhães wrote.

Mammals Were Small and Nocturnal During the Mesozoic, Says Researcher

According to the microbiologist, mammals went about life in a much different way during the era of dinosaurs. Mammals were positioned much lower on the food chain, and many were nocturnal to remain out of the sight of dinosaurs.

Source: Freepik

“For over 100 million years when dinosaurs were the dominant predators, mammals were generally small, nocturnal and short-lived,” said de Magalhães.

Pressure to Stay Alive Removes Important Longevity Genes

In his paper, De Magalhães suggests that the pressure to stay alive led to the elimination of genes required for the longevity witnessed in animals such as reptiles and others with much slower biological aging processes.

Source: Freepik

According to biologists, mammals during the Mesozoic era simply lost or deactivated their key longevity genes, which continue to affect humans in the modern era.

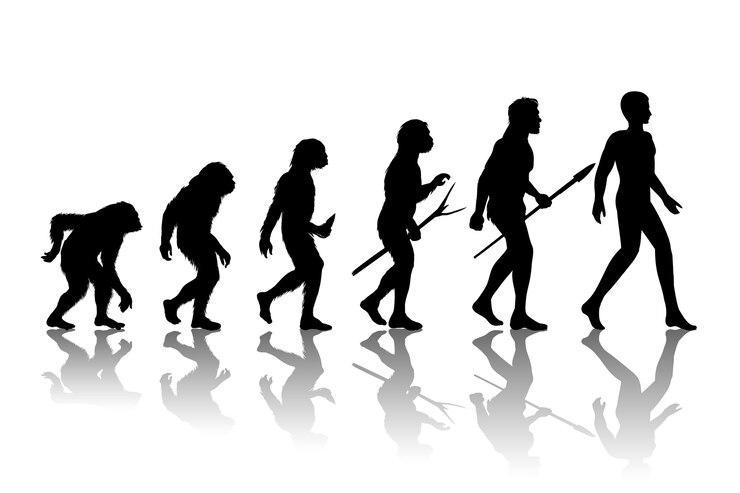

Dinosaurs Affected Humans Evolution

In a statement, de Magalhães explained, “Some of the earliest mammals were forced to live toward the bottom of the food chain and have likely spent 100 million years during the age of the dinosaurs evolving to survive through rapid reproduction.”

Source: Macrovector/Freepik

He continued, “That long period of evolutionary pressure has, I propose, an impact on the way that we humans age.”

Loss of Ability to Regenerate

After further research into his theory, de Magalhães believes he has come across evidence to suggest mammals lost certain enzymes during the Mesozoic Era, which also limited their ability to repair damage.

Source: Wikimedia

The biologist suggests mammals have lost the ability to continue growing teeth throughout their entire lifespan, and the enzymes that help restore skin are damaged by rays of ultraviolet light sent forth by the sun. All of which he blames on the dinosaurs.

Many Animals Have Impressive Regeneration

Despite the reproductive abilities of several animals around the world, ancient mammals did not prioritize genetic information and enzymes, as they were deemed unnecessary.

Source: Wikimedia

According to de Magalhães, mammals weren’t a priority during the Mesozoic because many were destined to become food for T. Rex and other enormous predators.

Humans Have the Last Laugh

De Magalhães admits that this research is little more than a hypothesis as it currently stands. But he claims it could help scientists better understand why humans evolved as we did.

Source: Freepik

He finished by stating, “There are lots of intriguing angles to take this, including the prospect that cancer is more frequent in mammals than other species due to the rapid aging process.” Nonetheless, even if dinosaurs are to blame for our shortened lifespans, humans did evolve to take the place of the Mesozoic reptiles at the tip of the food chain.

Why Do Reptiles Live Longer?

When it comes to longevity, scientists have long suspected that reptiles have an edge. Galapagos tortoises, eastern box turtles, cave-dwelling salamanders, and other reptiles and amphibians can live more than a century.

Source: Nilina/Pexels

For comparison, the oldest human on record lived to be 122 years old while a Seychelles giant tortoise named Jonathan just celebrated his 190th birthday and showed no signs of slowing down.

The Research Behind the Study

Most of the evidence highlighting the longevity of these animals has come from anecdotal reports from zoos, according to Beth Reink, a biologist at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, (via Popsci).

Source: Freepik

She and a team of more than 100 researchers from around the world have compared the aging rates in 77 species of reptiles and amphibians in the wild. “We wanted to know how widespread that is,” Reinke says.

The Varying Lifespans

Researchers found that aging and lifespan varied greatly from one species to the next. Turtles, crocodilians, and salamanders generally aged very slowly and had disproportionately long lifespans for their size.

Source: Freepik

However, another group of researchers in Denmark reached similar conclusions after comparing 52 species of turtles and tortoises living in zoos and aquariums.

Details About the Study

Reinke and her collaborators drew from long-running studies on a wide variety of animals for their study and tracked reptile and amphibian populations over an average period of 17 years.

Source: Wikipedia

This study encompassed more than 190,000 individual animals.

Estimating the Lifespan

To determine how quickly a species ages, the team calculated the rate at which individual members of these species died overtime after hitting sexual maturity. The team estimated the species’ lifespan from the number of years it took for 95% of these adult animals to die.

Source: Bigmacthealmanac/Wikipedia

Reinke notes that these estimates don’t distinguish the difference between causes of death. “When people hear ‘aging,’ they tend to think of just physiology. Our measure of aging includes not just physiology, but all things that could cause death in the wild,” she says.

The Lifespan Varies

When compared to a group of birds and mammals with slower metabolisms that put less wear and tear on their bodies, the results of whether or not reptiles and amphibians would live longer varied.

Source: Freepik

Longevity in reptiles and amphibians varied from 1 to 137 years—a much wider range than the 4 to 84 years seen in primates.

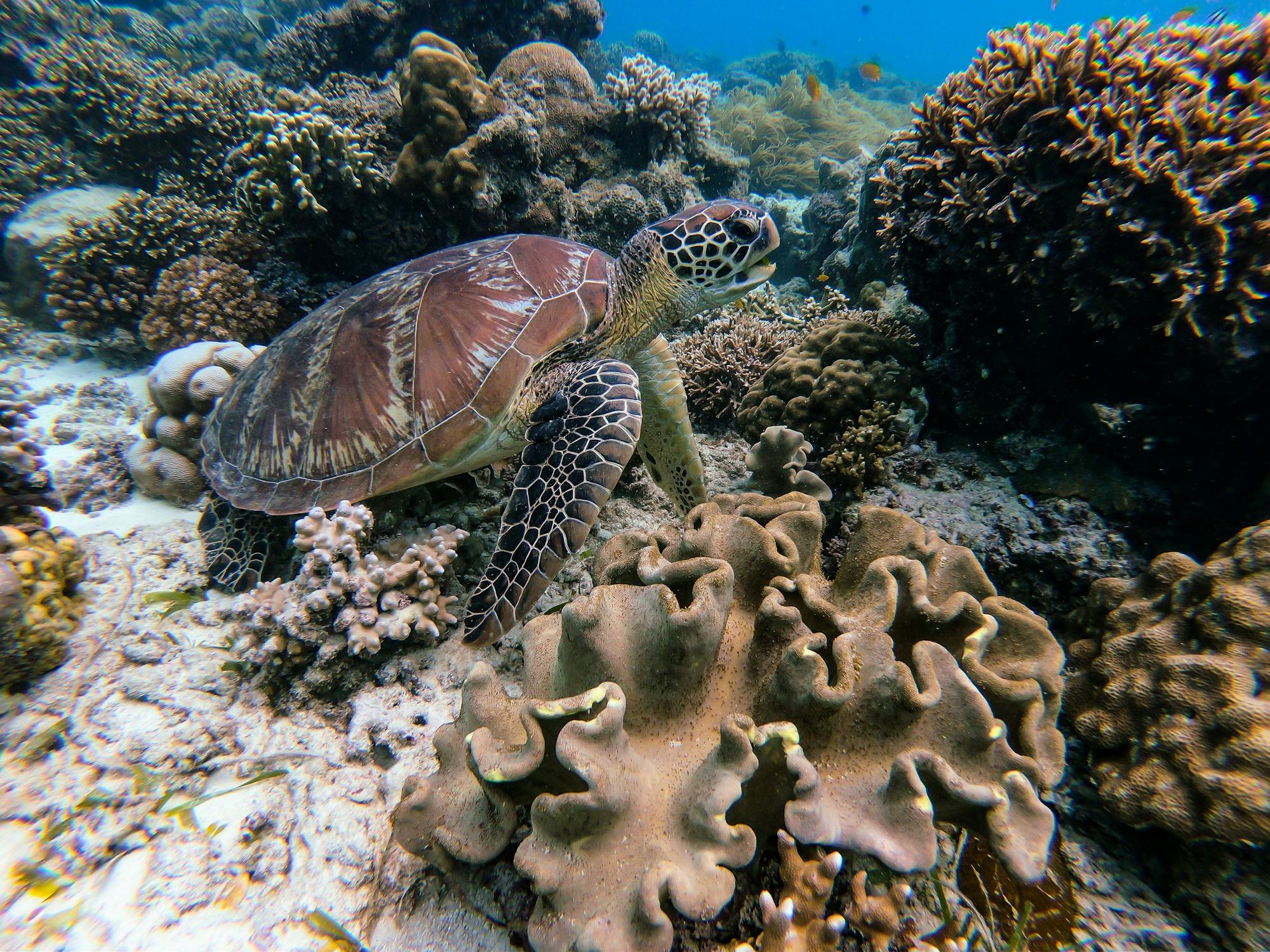

Turtles Are Living the Longest

However, one thing can not be denied: Turtles, as a group, were “uniquely slow agers,” she says.

This could be because turtles come equipped with characteristics that help them live longer, including a protective shell, scaly armor, or venom. In reptiles and amphibians, species that began reproducing later in life ended up living longer.

Factors That Need to be Explored

The team also found that reptiles that lived in warm temperatures aged more quickly, while amphibians that lived in similar conditions aged more slowly.

Source: Freepik

The results of the study, unfortunately, prove that much more research is needed to see how these and other variables drive differences in aging and longevity.

Interesting Patterns to Explore

“There are a lot of really interesting patterns that we brought to light that need to be explored further,” Reinke says.

Source: Danie Franco/Unsplash

She adds: “I think that ectotherms could have the answers to a lot of what we want to know about aging for human health.”

Another Study

In the Demark study, roughly 75% of the reptiles showed slow or negligible senescence while 80% aged more slowly than modern humans.

Source: Freepik

In both reports, their findings are not surprising, but challenge the idea of senescence, or a gradual decline in bodily functions that increases the mortality risk after an organism reaches maturity.

Adding to the Tree of Life

“They’re both excellent pieces of research,” Rob Salguero-Gomez, an ecologist at the University of Oxford, says. While Salguero-Gomez was not involved in any of these studies, he believes that our understanding of reptiles’ aging process is about to change.

Source: Freepik

“They add a new layer… upon our understanding of senescence across the tree of life,” he adds.