Scientists Detail How Stone Age Cultures Strategically Avoided Inbreeding

A new study published by a group of researchers proposes that Stone Age tribes living during the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods implemented deliberate plans to avoid inbreeding.

The scientists came to this conclusion after studying the remains of Stone Age humans who lived before the Farming revolution of Western Europe, which took place nearly 7,000 years ago. Further investigations could provide further insight into the early social structures of humans in this part of Europe.

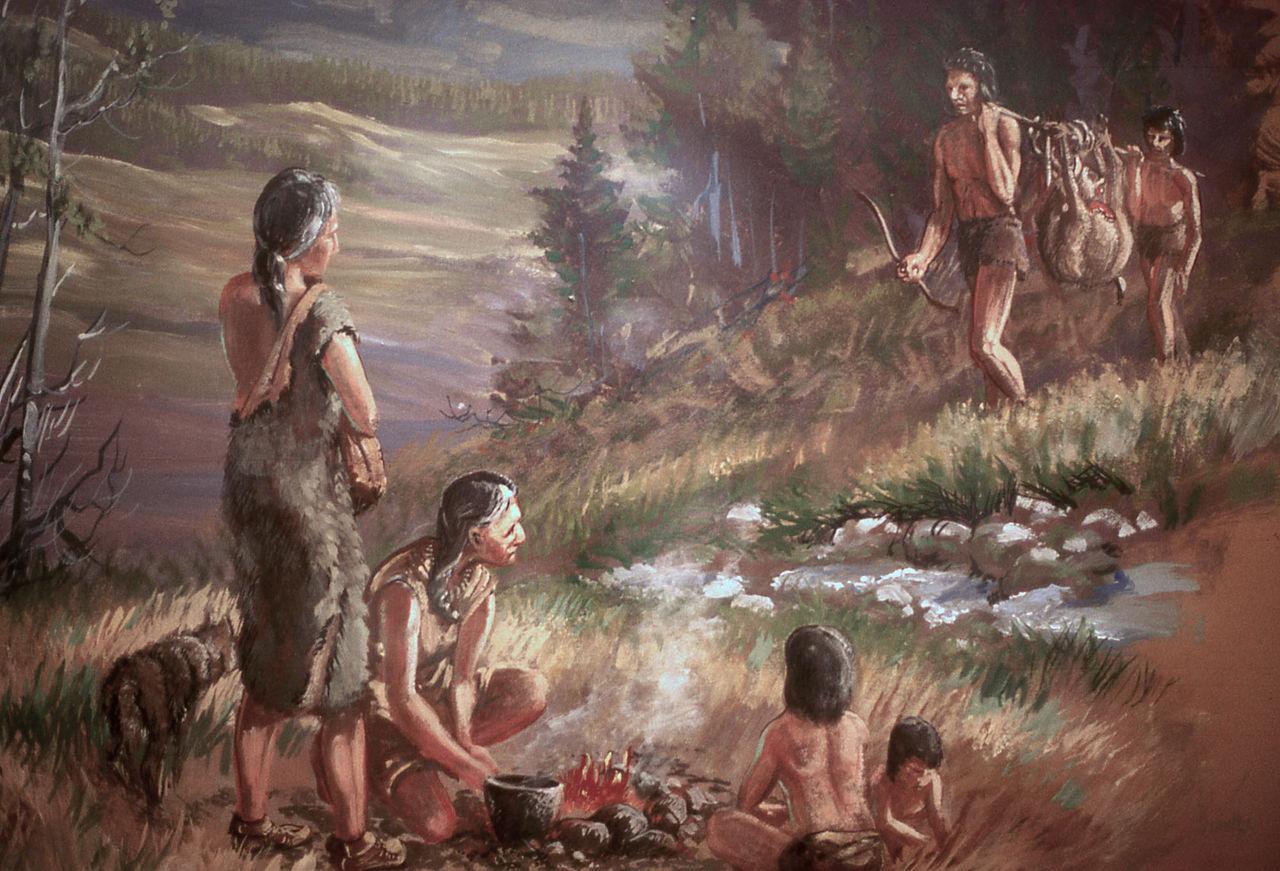

Humans During the Stone Age

Homo sapiens and our ancestral predecessors wandered Earth for hundreds of thousands of years, living a primarily hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

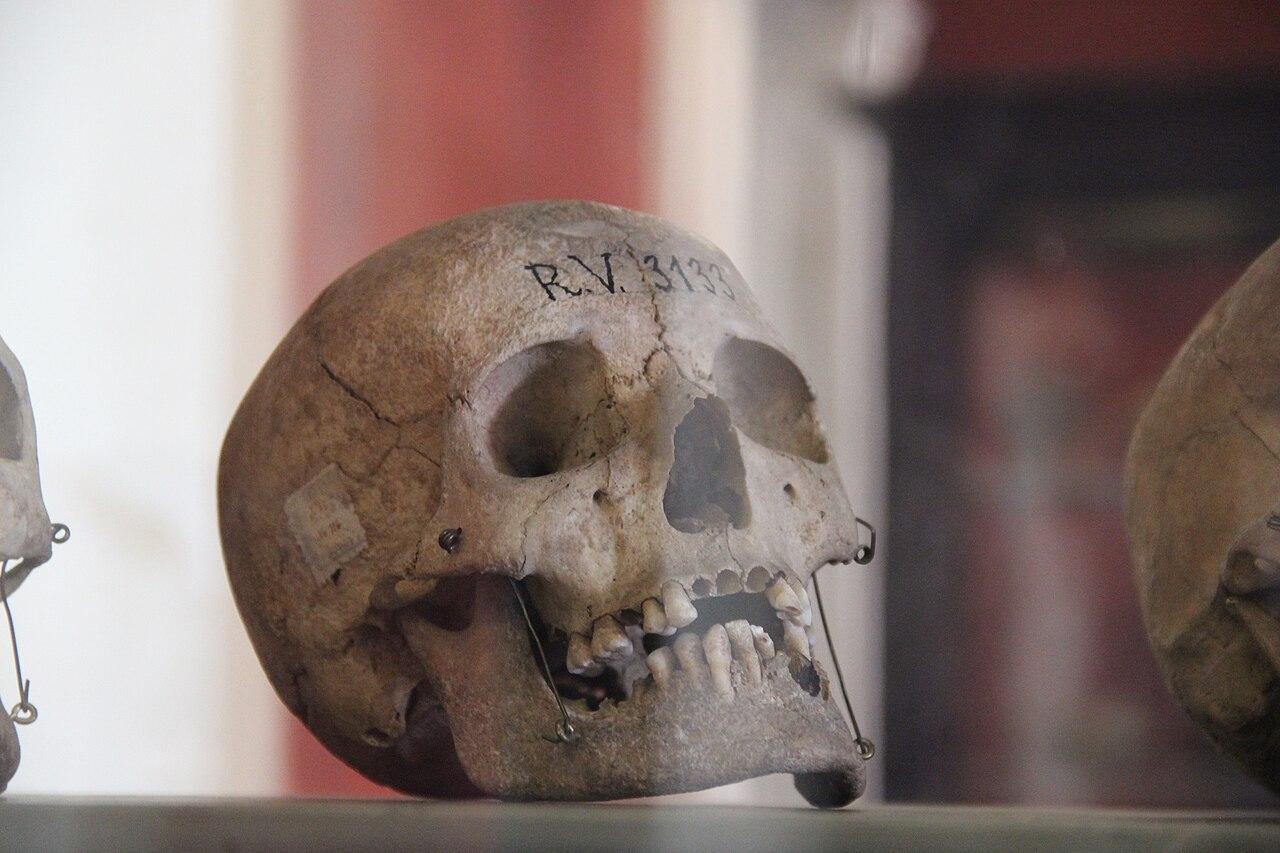

Source: Wikimedia

Anthropologists generally surmise that early humans lived in relatively small tribal groups. But this has always raised one question: How did our ancestors avoid inbreeding, a practice that could have had devastating consequences for the tribe’s future?

New Study Explains How Ancient Humans Avoided Inbreeding

A team of researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden embarked on a meticulous investigation to answer this question. Their journey began with the careful examination of the remains discovered at several Stone Age burial sites in Brittany, France.

Source: Freepik

Their groundbreaking study, published in PNAS, proposes that early humans were well aware of the dangers of inbreeding. They devised a deliberate system to ensure this was avoided at all costs.

The Emergence of Farming Societies in Western Europe

According to the study, the scientists successfully gathered biomolecular data from human remains discovered at sites including Hoedic and Teviec in Brittany and another site in Champigny.

Source: Wikimedia

The dating of the remains suggests the individuals lived at the tail-end of the Mesolithic period, around 6,700, during the transition between the end of hunter-gatherers in Western Europe and the emergence of a farming-based society.

Several Distinct Families Living in Close Proximity

The study’s lead author, Professor Mattias Jakobsson from Uppsala University, explained that their research was the first time scientists had analyzed the genomes of Stone Age hunter-gatherers who lived during the rise of Neolithic farming communities.

Source: Wikimedia

“This gives a new picture of the last Stone Age hunter-gatherer populations in Western Europe. Our study provides a unique opportunity to analyze these groups and their social dynamics,” he said.

Farming Communities Eventually Replace Hunter-Gatherers

Researchers suggest Western European hunter-gatherers began encountering the Neolithic farmers around 7,500 years ago. It’s thought the hunter-gatherers were eventually assimilated or replaced by the new immigrants.

Source: Wikimedia

However, over the past century, questions have been raised about the coexistence of these groups and to what extent they actually interacted with one another, if any.

Hunter-Gatherers Mixed With Groups of the Same Lifestyle

Based on isotope data, previous studies proposed that the remnants of the hunter-gatherer communities may have assimilated women from the farming societies to boost their numbers.

Source: Wikimedia

However, the new study contradicts this, suggesting that instead, the hunter-gatherers mixed with other groups of the same lifestyle and refrained from intermixing with the farming societies.

No Signs of Inbreeding

Luciana G. Simões, a researcher at Uppsala University, explained that the study’s results suggest that the hunter-gatherer groups were made up of diverse families unrelated to one another.

Source: Wikimedia

“Our genomic analyses show that although these groups were made up of few individuals, they were generally not closely related. Furthermore, there were no signs of inbreeding,” she said.

A Strategy to Avoid Inbreeding

According to Simões, the diverse nature of the hunter-gatherers was no mistake but instead intelligently planned out in an attempt to avoid inbreeding.

Source: Wikimedia

“However, we know that there were distinct social units – with different dietary habits – and a pattern of groups emerged that was probably part of a strategy to avoid inbreeding,” she said.

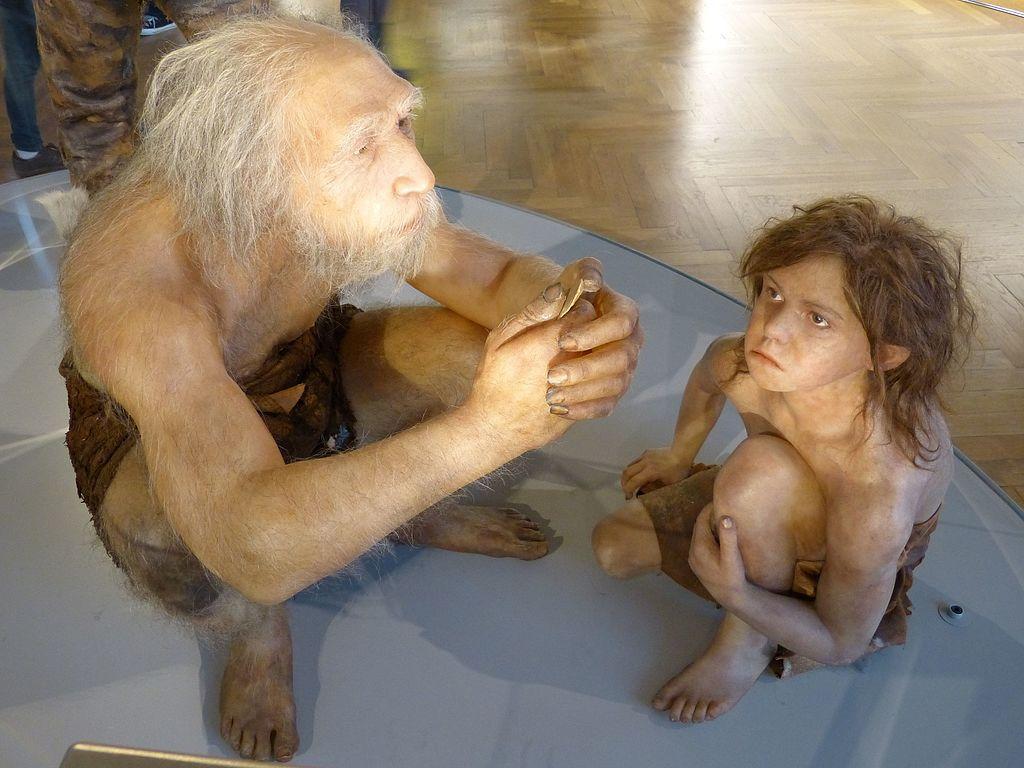

Mesolithic Burial Sites

Researchers from several French institutions, such as the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN) in Paris and the University of Rennes in Brittany, conducted the investigation.

Source: Wikimedia

Researchers from these institutions examined several sites in southern Brittany where numerous individuals were buried together. While this is considered unusual at Mesolithic burial sites, it was assumed they’d be biologically related; however, this hypothesis was proven false, surprising the researchers.

The Individuals Buried in Brittany Weren’t Released

Dr Amélie Vialet from the Muséum National d’Histoire naturelle explained, “Our results show that in many cases – even in the case of women and children in the same grave – the individuals were not related.”

Source: Wikimedia

She added, “This suggests that there were strong social bonds that had nothing to do with biological kinship and that these relationships remained important even after death.”

Stone Age Europeans Reduce the Chance of Inbreeding

The findings of the recent study have provided researchers with valuable insight into the lives of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and how they avoided inbreeding during the transition to farming-based societies.

Source: Wikimedia

It also showcases the intelligence of early humans, who deliberately implemented plans that resulted in unrelated families living together, clearly aimed at reducing the likelihood of inbreeding.