Scientists Discover Chernobyl Worms Have ‘Superpower’ in Which They’re Immune to Radiation

Worms are resilient creatures. Worms growing in Chernobyl, Ukraine, the site of the world’s most infamous nuclear disaster, are even more so.

Chernobyl worms seem to have grown a ‘superpower’: They are immune to radiation. Scientists must study these worms further, so they took them to New York for further observation. The results may have a significant impact on human health.

Discovered by NYU Researchers

Several researchers from New York University discovered the worms in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. They collected the worms from soil samples, rotting fruits and other materials.

Source: sands_dunc53795/X

Later, they tested the worms for radiation. Once it was discovered that the worms didn’t carry any signs of radiation, they were frozen and sent to the lab at NYU.

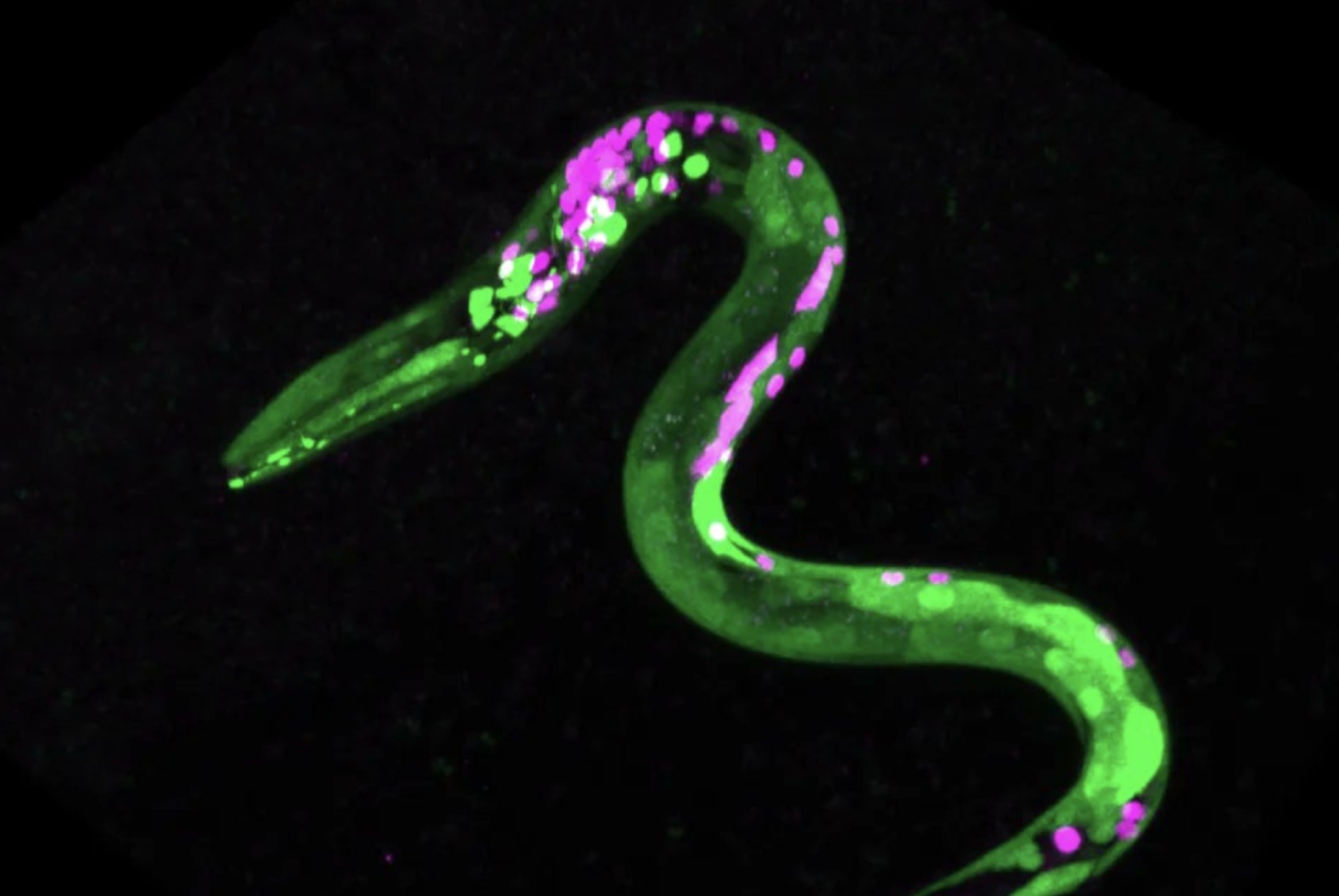

Genomes Undamaged

The worms were of a nematode species called Oscheius tipulae. This species has previously been used in studies of genetics and evolution.

Source: CarlosP95095856/X

After using several different analytical techniques, researchers were surprised to not find any signature of radiation damage on the genomes of these tiny, microscopic Chernobyl worms.

Levels of Radiation Also Vary

When scientists collected the worms from various materials, different radiation levels were found within the zone. This might have affected the worms’ conditions.

Source: Kevin B/Pexels

Radiation levels could go from low, which normally would be found in large cities like New York, to high, which are usually found in outer space. But the impact on the worms was similar: Their genome was undamaged by radiation.

Scientists Still Studying the Disaster’s Effects

Around four decades after the Chernobyl incident, scientists are still often mystified by findings there. This particular research team, which published their study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), is among them.

Source: Viktor Hesse/Unsplash

The research team’s lead author, Dr. Sophia Tintori, told the Daily Mail, “Chernobyl was a tragedy of incomprehensible scale, but we still don’t have a great grasp on the effects of the disaster on local populations.”

Selection of the Species

She continued, “Did the sudden environmental shift select for species, or even individuals within a species, that are naturally more resistant to ionizing radiation?”

Source: Colin Davis/Unsplash

She had a good reason to question whether select species are more affected than others because some animals living in the zone have been found with physical and genetic differences from the same creatures found outside the zone.

Differences in Creature Evolutions

40 years after the disaster in 1986, Chernobyl and its surrounding areas are still plagued by persistent radiation. But animals continue to live there even though it means their genetic makeup has changed.

Source: Shelby Waltz/Pexels

Animals like frogs and wild dogs (wolves) have undergone genetic mutation in Chernobyl. Frogs that should have been green in color turned black from being exposed to higher radiation. And wolves in the zone developed a different immune system and are more resistant to cancer.

The Worms Are Different

But the worms are clearly different from these animals. For one, their genetic makeup is simpler, and they go through the evolutionary process at a much faster speed.

Source: Sippakorn Yamkasikorn/Pexels

A biology professor at NYU, Matthew Rockman, remarked, “These worms live everywhere, and they live quickly, so they go through dozens of generations of evolution while a typical vertebrate is still putting on its shoes.”

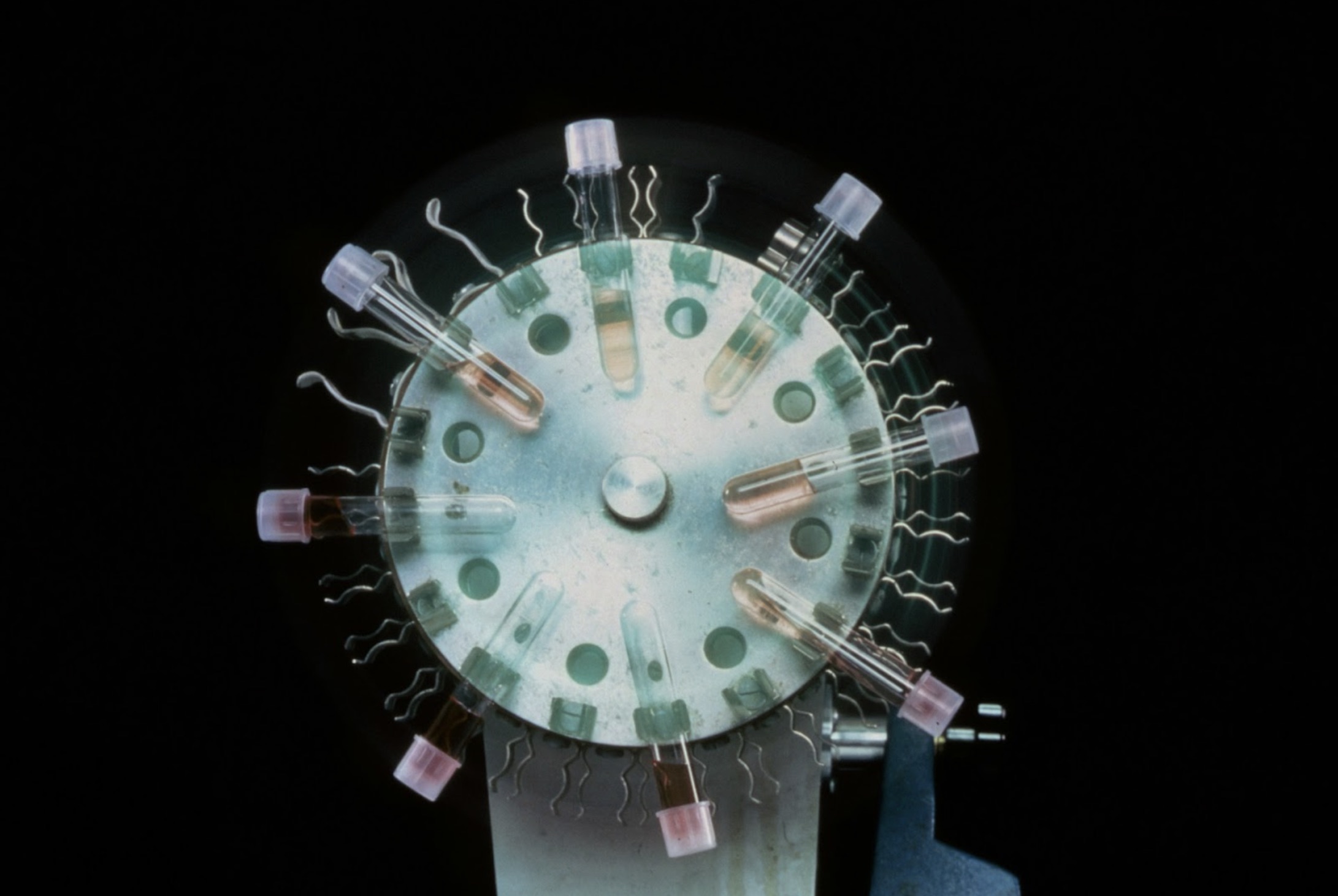

Cryopreserving the Worms

Scientists in the lab stop the evolution from happening by a process called cryopreserve, or “freezing the worms.” They “thaw them for study later,” Professor Rockman then explained.

Source: Manuela Nagel2/Wikimedia Commons

By stopping evolution in the lab, which is impossible with other animal models, scientists find it “very valuable when we want to compare animals that have experienced different evolutionary histories.”

Chernobyl Still Unsafe

The study may prove that certain organisms can survive in Chernobyl, but it is by no means a safe place to live. “This doesn’t mean that Chernobyl is safe,” Dr. Tintori emphasized. “It more likely means that nematodes are really resilient animals and can withstand extreme conditions.”

Source: Yves Alarie/Unsplash

She said the research team was also unsure about “how long each of the worms we collected was in the zone.” Therefore, the researchers couldn’t be sure exactly “what level of exposure each worm and its ancestors received over the past four decades.”

Understanding DNA Damage

The nematodes’ genetic makeup is simple compared to a human being’s, yet these findings may lead to a better understanding of humans’ natural variations.

Source: Independent/X

“Now that we know which strains of O. tipulae are more sensitive or more tolerant to DNA damage, we can use these strains to study why different individuals are more likely than others to suffer the effects of carcinogens,” Dr. Tintori concluded.

Beneficial for Cancer Studies

Studying different individuals in a species responding to DNA damage is a top priority for cancer researchers. They still want to understand why some humans are genetically predisposed to develop cancer, while others don’t.

Source: National Cancer Institute/Unsplash

Dr. Tintori added, “Thinking about how individuals respond differently to DNA-damaging agents in the environment is something that will help us have a clear vision of our own risk factors.” Let’s all hope these worms can further the research on cancer for the good of humankind.