Scientists Unearth a 520 Million-Year-Old Fossil With Its Brains and Guts Still Intact

A team of researchers has discovered an extremely rare fossil belonging to the arthropods group, which includes creatures such as spiders, centipedes, and crabs. What made this discovery so remarkable was the presence of its brain and guts, both of which were still intact.

The unique findings can potentially revolutionize our understanding of the early evolution of arthropods.

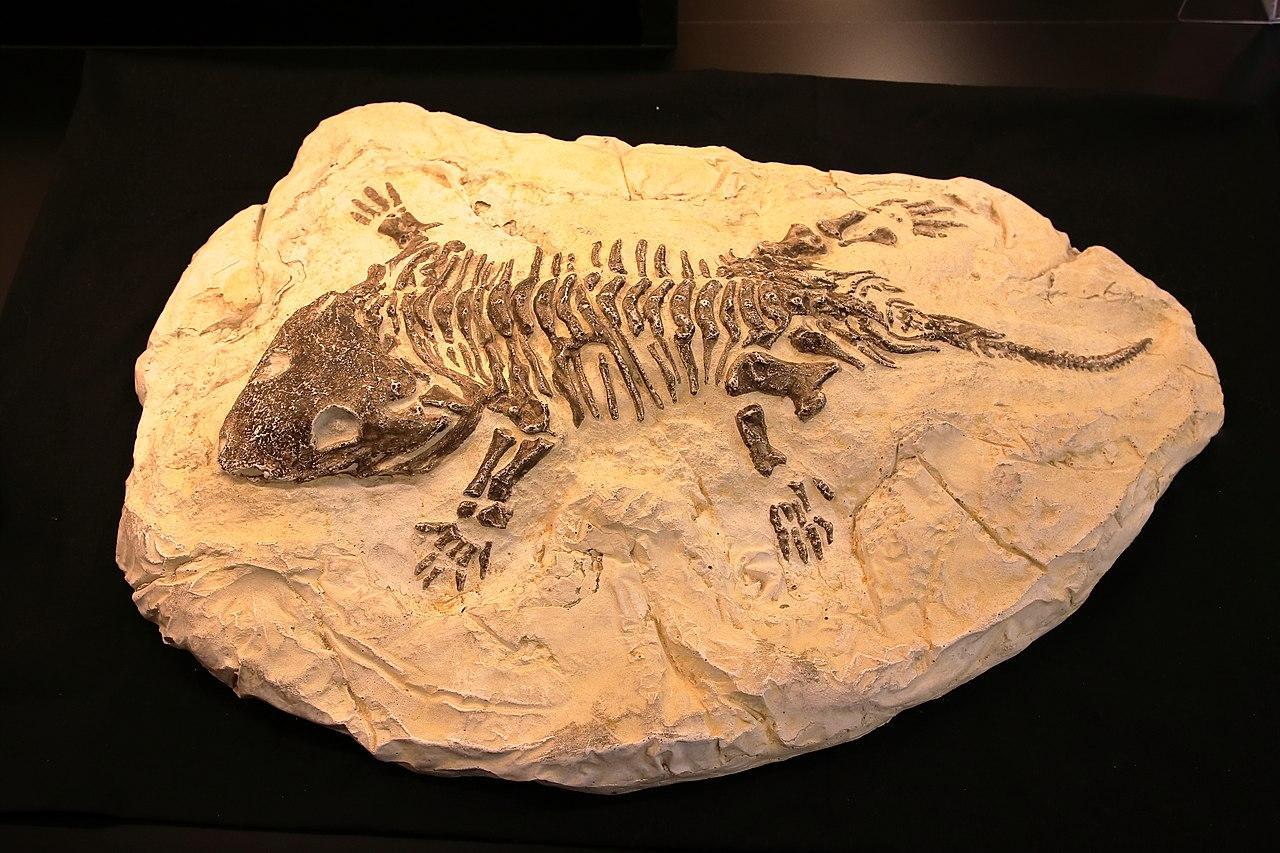

Fossils Retell the Story of Evolution

The fossilized remains of animals have played a significant role in shedding light on Earth’s history and showcasing the various evolutionary paths species took to become what they are today.

Source: Wikimedia

Fossils come in all shapes and sizes: sometimes, a minor fragment is unearthed, whereas, on rare occasions, the entire skeletons of an ancient animal are pulled from the ground.

Why Doesn't Tissue Typically Fossilize?

Generally, most fossils are found in conditions unfavorable to soft tissue, meaning the innards of animals usually decay rapidly, leaving only the fossilized remains of bones.

Source: Wikimedia

Certain minerals must be present in the environment for fossils to preserve soft tissue, which can prevent microbes from breaking down the body. This does happen on rare occasions, and one such example was recently unearthed in China.

The Discovery of a Fossil With Brains and Guts Intact

A team of researchers stumbled upon the fossilized remains of a small poppy-seed-sized worm that dates back to the Cambrian period over 520 million years ago.

Source: Wikimedia

What made this discovery unique was the presence of soft tissue, including the creature’s brain and guts, which somewhat remained intact due to the conditions under which its fossilized

The Find of a Lifetime, Says Researcher

Paleontologist Martin Smith of Durham University in the UK shared his thoughts on the exciting discovery, explaining that it was the find of a lifetime.

Source: Freepik

“When I used to daydream about the one fossil I’d most like to discover, I’d always be thinking of an arthropod larva, because developmental data are just so central to understanding their evolution,” he said.

The Rarity of the Larvae Discovery

According to Smith, the chances of stumbling upon the fossilized remains of larvae are virtually zero, further adding to the rarity of the find.

Source: Wikimedia

“I already knew that this simple worm-like fossil was something special, but when I saw the amazing structures preserved under its skin, my jaw just dropped – how could these intricate features have avoided decay and still be here to see half a billion years later?” he added.

Researchers Conduct Study on Unique Larvae Fossil

Katherine Dobson, one of the researchers involved in a study of the recent discovery, explained, “It’s always interesting to see what’s inside a sample using 3D imaging.”

Source: Freepik

The co-author of the study added, “But in this incredible tiny larva, natural fossilization has achieved almost perfect preservation.”

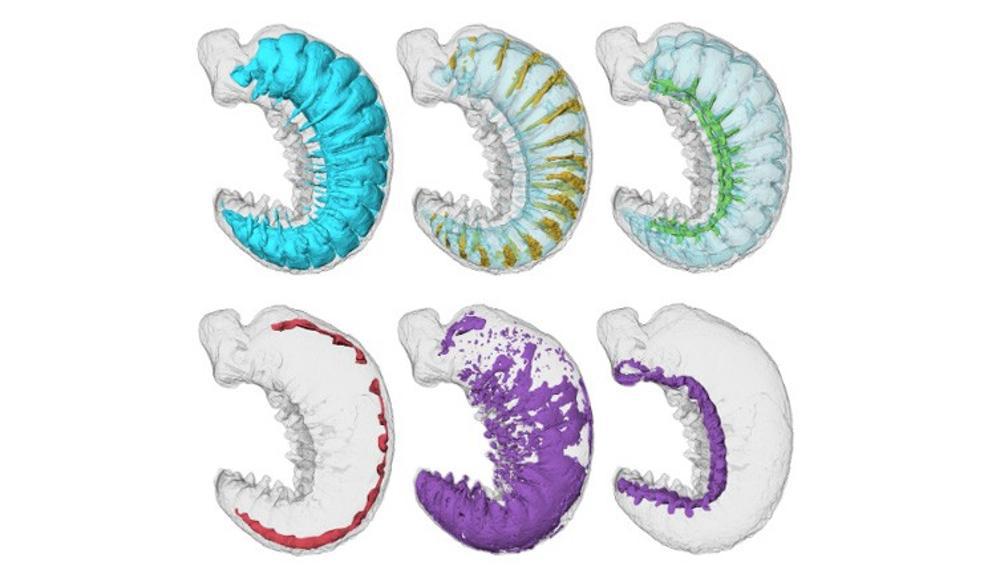

Researchers Use X-Rays to Study the Creature

The small fossil’s “almost perfect preservation” greatly excited evolutionary biologists, who began studying the creature using a plethora of 3D images produced using X-ray tomography.

Source: Smith et al. 2024

This allowed researchers to observe the creature’s brain, parts of its “digestive glands, a primitive circulatory system and even traces of the nerves supplying the larva’s simple legs and eyes.”

The Complexity of Early Arthropods

Scientists were shocked by the level of detail in the specimen, which is over half a billion years old. The arthropod discovered in China was also the first of a whole new genus, Youti yuanshi.

Source: Dotted Yeti/Shutterstock

The study’s insights have drastically altered the researcher’s perception of early arthropods, suggesting they were far more complex than initially theorized.

Scientists Make Connections Between Ancient and Modern Arthropods

The meticulous examination of the larvae also allowed researchers to make evolutionary connections between the ancient creatures of the Cambrian period and those that roam Earth today.

Source: Freepik

Scientists noted a region in the brain called the protocerebrum in the Cambrian larvae. They suggest the latter eventually evolved into the “nub” observed in modern arthropods, enabling them to survive in various environments around Earth, including Antarctica.

How Arthropods Thrived During the Cambrian Explosion of Life

“Arthropods are an incredibly diverse group of animals,” explained Emma Long, one of the co-authors of the study.

Source: Wikimedia

She added, “Their evolutionary success is often attributed to their segmented body plan. The basic blueprint of a single segment, which includes a pair of appendages, can be modified into something highly specialized. For instance, limbs become sensory antennae, and claws become jaws.”

The Evolution of Arthropods

Studies like those conducted on the fossilized remains of creatures such as the Cambrian-era larvae have played a significant role in furthering our understanding of how these early arthropod groups evolved to become the species they are today.

Source: Wikimedia

The discovered fossil is currently on display at Yunnan University in China, which is not far from where it was initially discovered.