The Return of the Tasmanian Tiger: How RNA from a 132-Year-Old Specimen Could Make It Possible

The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step, and that applies as well to returning some of the earth’s beautiful but extinct animals. Scientists plan to replace the Tasmanian Tiger by cloning its RNA, a procedure some are saying is straight out of the Jurassic Park movies.

Join us as we explore this exciting story and get a peek at what the future holds for extinct animals.

The last Tasmanian Tiger died over 100 years ago.

Tasmanian Tigers, also known as thylacines, numbered around 5,000 when the first Europeans settled in Australia. Unfortunately, their population died quickly due to disease and overhunting by these settlers.

Source: @TopicalPressAgency/Getty Images

This overhunting happened because the Tasmanian Tigers frequently killed livestock, causing the government to issue a bounty to hunters. Eventually, it went extinct on September 7th, with the last member of the species dying at Beaumaris Zoo.

"It could return…" scientists say

Bringing back the Tasmanian Tiger is a massive project by Professor Andrew Pask, who heads the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research Lab. He says that returning this species involves a complete reconstruction of its genome and then comparing it with its closest relative, the Dunnart.

Source: Wikipedia

It’s also possible to alter the genome of the Dunnart and make it similar to the thylacines, allowing one Dunnart female to surrogate the animal back to life.

Searching for the Beaumaris Zoo's last Tasmanian Tiger

The last member of the thylacines died on September 7th at Beaumaris Zoo and was later sent to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. However, since the animal wasn’t on display, the gallery thought the species may have been thrown out over the years.

Source: @FollowAlice/Pexels

For years, researchers and museum curators searched for the last well-preserved Tasmanian corpse. Unfortunately, the search was unsuccessful, as no thylacine material existed in the museum catalog in 1936.

A clumsy mistake, a satisfying discovery

Traces of the dead Tasmanian Tiger were unavailable at the museum because they were never added to the catalogs. This realization led researchers to an unpublished taxidermist’s report for the material.

Source: Stockholm University

After visiting this report’s source, the museum went through its collection and eventually found Benjamin’s remains. He was stuffed in a cupboard in the institution’s education department.

A sigh of relief and an embarrassing discovery

While the animal’s hide was well preserved and came with a traveling exhibit, they didn’t know their display was the last Tasmanian tiger. Eventually, it was taken and returned to the museum for further inspection.

Source: @Karatara/Pexels

Surprisingly, this inspection showed that the last thylacine, Benjamin, was female, not the previously believed male. While an embarrassing mistake from the past, it’s better than completely losing such an essential part of history.

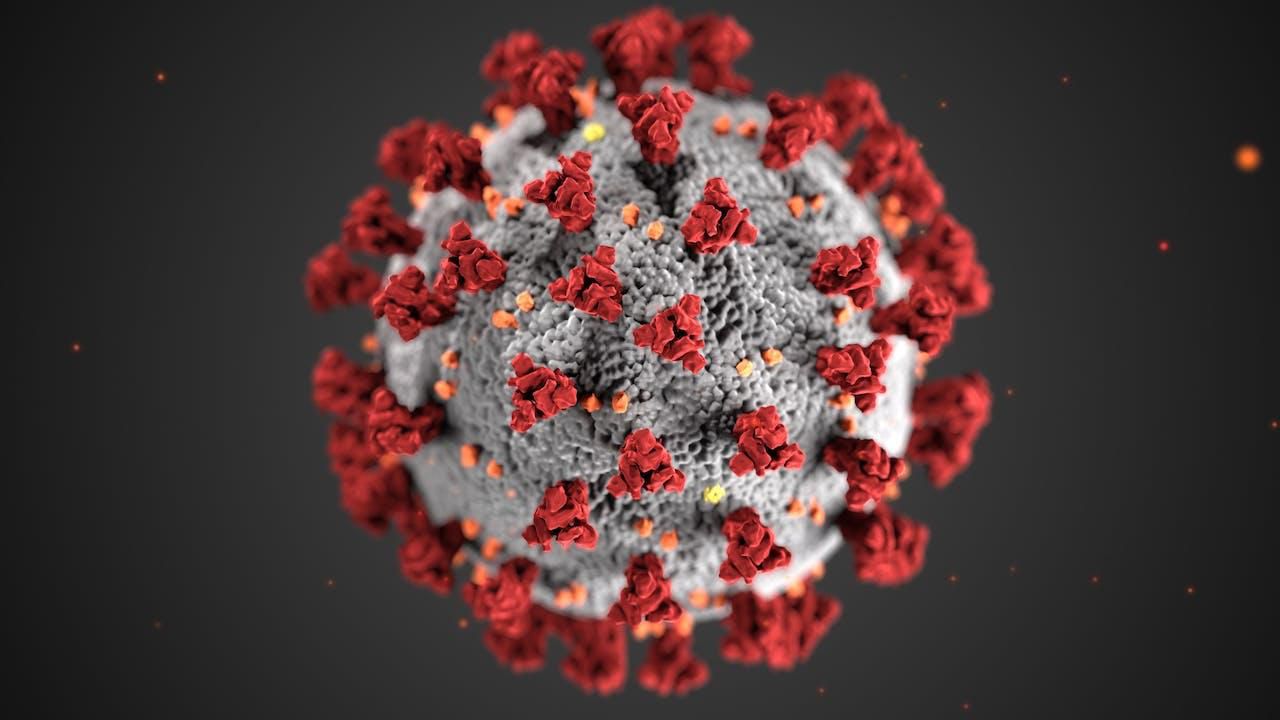

Resurrecting the thylacine from a 132-year-old slumber

Now that Benjamin’s hide has been analyzed, scientists can retrieve its RNA and allow this ancient creature to roam free in the wild. The team spent hours extracting millions of RNA sequences from Benjamin’s tissue, which is the first time such a procedure has been done successfully.

Source: Wikipedia

According to Marc R. Friedländer, associate professor at the Department of Molecular Biosciences, “This is the first time that we have had a glimpse into the existence of thylacine-specific regulatory genes…that went extinct more than a century ago”.

But why take the RNA? Shouldn't it be the DNA?

It’s possible to clone an animal with its DNA; however, most movies make this seem like the only method for resurrecting a dead species. The scientists took the Tasmanian RNA because it contains the coding sequences of the genes that encode the proteins of the animal better than DNA.

Source: @NothingAhead/Pexels

While DNA is more stable, RNA lasts longer and is less prone to contamination over the years, which makes sense for this procedure. Ultimately, using RNA lets them get a more accurate representation of the animal’s genetic makeup.

Not everyone's on board the resurrection train.

Naturally, bringing an extinct animal back to life will bring some controversies and debate, dividing the scientific community and the public. Some support the resurrection, stating that it can restore biodiversity, improve scientific understanding, and satisfy human curiosity.

Source: @StivenRivera/Pexels

They believe species that were unfairly treated, like the extinct Dodo bird, can have a chance at life. Also, bringing back the Tasmanian devil can boost tourism and education in Australia.

Resurrection can cause more harm than good.

On the other hand, people against bringing back the Tasmanian Tiger say it could disrupt the natural balance of the ecosystem, disrupt wildlife, create new diseases, and violate animal rights.

Source: @CDC/Pexels

It could also divert attention from preserving already-existing species at the brink of extinction. Some people even question the moral implications of playing God as it cheapens the value of life.

When will the resurrection begin?

More studies and research are needed to bring back this extinct animal, and the scientists in charge hope to do so in 10 years. They plan to use gene editing and stem cells to recreate the genome and insert it into a host embryo.

Source: @UniversalHistoryArchives/Getty Images

The project is a collaboration between the University of Melbourne and Colossal Biosciences, a company also working on bringing back the woolly mammoth.

Conclusion

The return of the Tasmanian Tiger is a fascinating topic, where using RNA from a 132-year-old Specimen may revive this extinct animal. However, this also raises many ethical and environmental questions that must be addressed before proceeding with this ambitious project.

Source: @ChrisLane/Getty Images

Let us know what you think about bringing back the Tasmanian Tiger. Please share your thoughts and opinions with us in the comments section below. Thanks!