The World’s Oldest Ritual Performed by 500 Generations Has Been Rediscovered by Archaeologists

Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of an Indigenous ritual in Australia. A new study reveals that people practiced the 12,000-year-old ritual continuously for 500 generations.

A team of researchers made the discovery in a cave located in the southeast of the country.

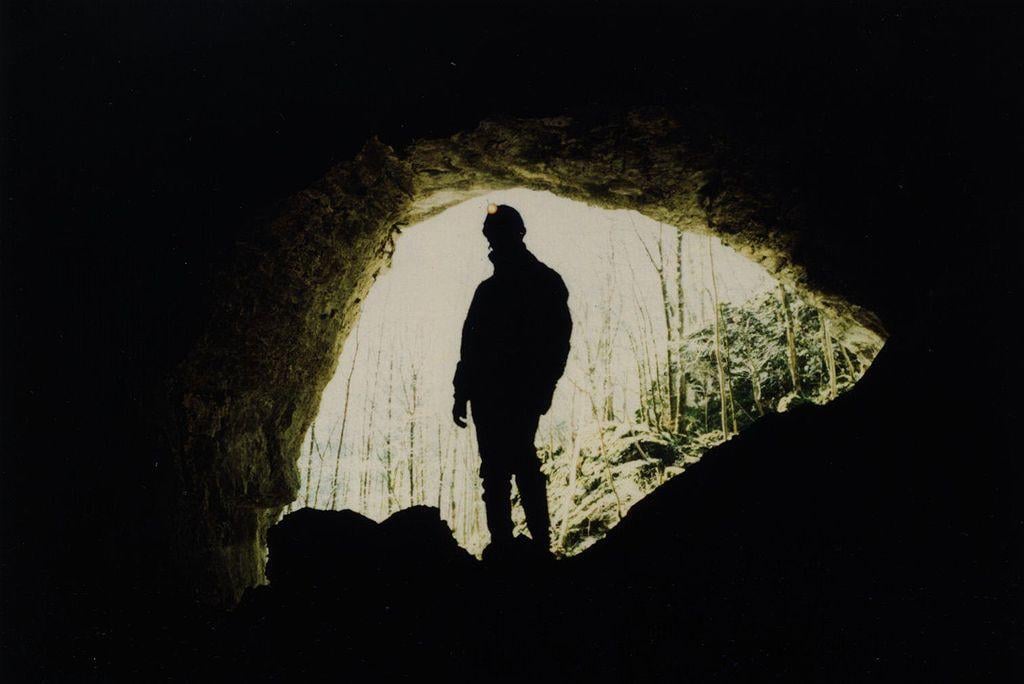

Investigating the Cloggs Cave

While investigating Cloggs Cave, situated near Buchan, a small town in Australia 217 miles east of Melbourne, researchers found wood protruding out of the ground.

Source: Eugene Badusev/Wikimedia Commons

After cutting the wood, the team used carbon dating to determine the age. The wood dates back to 12,000 years old, from the end of the last Ice Age.

Documenting the Discovery

The latest discoveries, documented in a study published in the journal “Nature Human Behaviour,” shed light on the rich cultural heritage of the Gunaikurnai—an Aboriginal Australian nation that is one of the world’s oldest living cultures.

Source: Wikimedia

The investigations uncovered two miniature fireplaces, each featuring a single-shaped wooden stick embedded within them.

Dating the Wooden Stick

But the wooden stick, which was 1,000 years younger, was remarkably similar. Researchers found both sticks smeared with animal or human fat next to miniature fireplaces.

Source: Science Photo Library

Both had been “fleeting burnt,” as detailed in a Nature Human Behaviour article published in August. The team believes the sticks were used by the Gunaikurnai people.

Artifacts Don’t Survive This Long

“And we were going ‘Wow, what’s this?’ Bruno David, a professor at the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre in Australia who co-authored the paper, said in a recorded conversation shared with CNN.

Source: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

“12,000-year-old artifacts don’t survive in the ground for that long. Normally they just disintegrate.”

Reaching Out

The Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC), which represents the Gunaikurnai people, approached David and his colleagues at Monash University to investigate the archaeological evidence of this ritual.

Source: Jessica Shapiro/National Museum of Australia

Experts believe the findings represent the “oldest archaeological evidence” of a ritual that modern ethnographers, who study and describe the culture of specific societies or groups, have documented.

The Ritual

The ritual was previously documented by 19th-century geologist and ethnographer Alfred Howitt. He details the rituals carried out in Cloggs Cave by the Gunaikurnai people, whom he calls “sorcerers,” “wizards,” or “medicine men and women,” though they are known as “mulla-mullung” among the Gunaikurnai people.

Source: Wikimedia

The ethnographer notes that their rituals would seek to harm adversaries or heal the sick by finding something belonging to the subject and attaching it to a throwing stick along with human or animal fat.

The Practice Continues to Exist

The throwing stick was then stuck slanted in the ground before a fire was lit in the miniature fireplaces. The mulla-mullung would then chant the name of the sick person. Once the stick fell, the charm was complete.

Source: Hugo Heimendinger/Pexels

Howitt observed that the stick was made of Casuarina wood and noted that the practice still existed in the late 1800s when he was writing.

Easily Missing the Evidence

Gunaikurnai Elder Uncle Russell Mullett told CNN that the discovery could easily have been missed in the cave, but he credited ‘the spirits that still live’ in the area for helping researchers unearth it.

Source: Wikimedia

“Bringing in the community way, the cultural way, with some of the scientific techniques, means that stories can be told,” David said. “And if you take just one or the other… those things wouldn’t speak to you in that way.”

Connecting the Dots

There are several connections between the archaeological evidence and 19th-century ethnographic observations, according to David.

Source: Freepik

“It’s possible in theory that the practice stopped and then started again, but if that was the case, its cultural knowledge would still have had to have been transmitted from generation to generation through that intervening time, as the individual, and combination, of the multiple details that make up the ritual installation are too unusual to be recreated in this precise combination out of the blue,” David said.

A Reminder of the Past

Gunaikurnai Elder Mullett notes that this discovery could benefit the community, even though European settlers interrupted the traditional knowledge and stopped the practice of the ritual in the 1860s.

Source: Museum of Cultural History/University of Oslo

“Gunaikurnai people were moved off our Country and onto mission stations,” he said. “Families were broken up, and we were forbidden to practice our culture or speak our language. The impacts of these colonial decisions are still felt by our community today, which is why these discoveries and reclamation of our connection to culture are so essential.”

A Living Culture

“For these artifacts to survive is just amazing. They’re telling us a story,” Mullett said in the press release.

Source: GLaWAC

“A reminder that we are a living culture still connected to our ancient past. It’s a unique opportunity to be able to read the memoirs of our Ancestors and share them with our community… It’s only when you combine the Western scientific techniques with our traditional knowledge that the whole story can start to unfold.”