The Unique Story Of The 19th-Century Shipwrecks Buried Beneath Kansas Cornfields

Would you believe that beneath the fertile soil of Kansas, a state known more for its wheat than waterways, lie buried shipwrecks from a bygone era? It’s a startling fact. The remnants of 19th-century steamboats, once gliding along the Missouri River, now rest under cornfields, far from any visible body of water.

This peculiar aspect of Kansas’ geography highlights a forgotten chapter of American history, intertwining the fate of pioneering steamboats with the shifting landscapes of the Midwest.

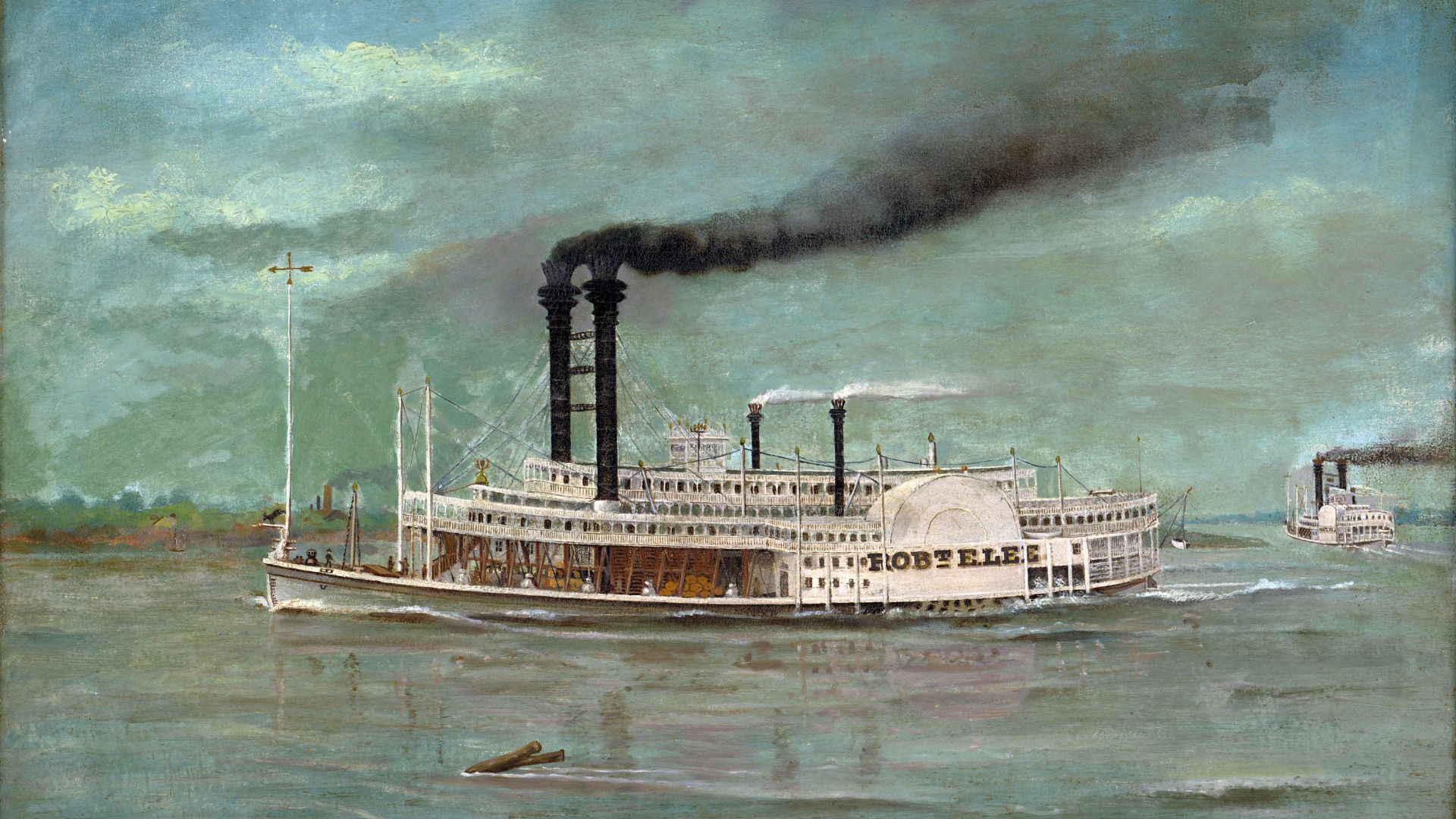

The Creation Of The Great White Arabia

In 1853, the Great White Arabia was built in West Brownsville, Pennsylvania. John S. Pringle’s boatyard saw the creation of this great steamboat.

Source: Michael Barera/Wikimedia Commons

Created to carry both cargo and passengers, the Arabia could tout that it was 171 feet long. Steamboats during this time could vary in size. Some smaller boats would only be 50 to 100 feet, while larger ones would be nearly 150 feet in length or more.

The Great White Arabia’s Final Journey

On a fateful day in 1856, the steamboat Great White Arabia struck a submerged log in the treacherous waters of the Missouri River and sank rapidly. Unlike many vessels of its time, the Arabia was laden not with gold or bourbon, but with 220 tons of cargo destined for frontier towns.

Source: The Arabia Steamboat Museum

This included everything from food to hardware, intended for the burgeoning communities along the river’s banks. Unbeknownst to those communities, the Arabia’s final resting place would not be in the river’s depths but beneath a future Kansas cornfield (via The Arabia Steamboat Museum).

The Sinking Of The Great White Arabia

The Arabia didn’t only have cargo on board. The ship also carried about 150 crew and passengers. While many steamboat wrecks of this time could end in the loss of human life, the Arabia was lucky.

Source: Michael Barera/Wikimedia Commons

None of the passengers died after the boat hit a log in the water. All managed to survive and get off the boat safely — even though the Arabia ended up sinking in just a few minutes.

An Eyewitness Account Of The Sinking

During the time of the Arabia’s sinking, an eyewitness account was recorded of what exactly happened by a passenger who survived named Abel Kirk.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

“There was a wild scene on board,” Kirk said. “The boat went down till the water came over the deck, and the boat keeled over on one side. The chairs and stools were tumbled about and many of the children nearly fell into the water.”

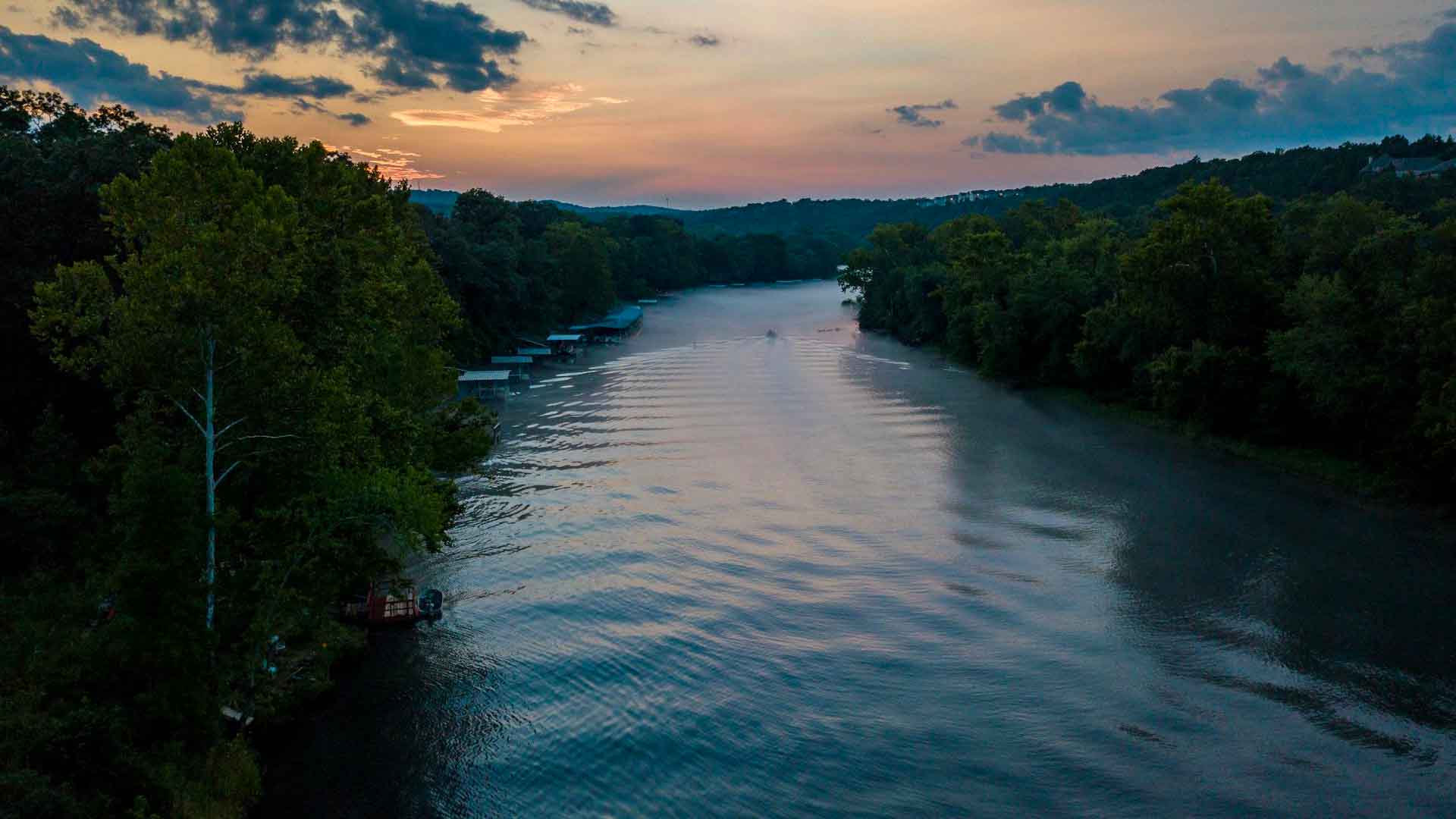

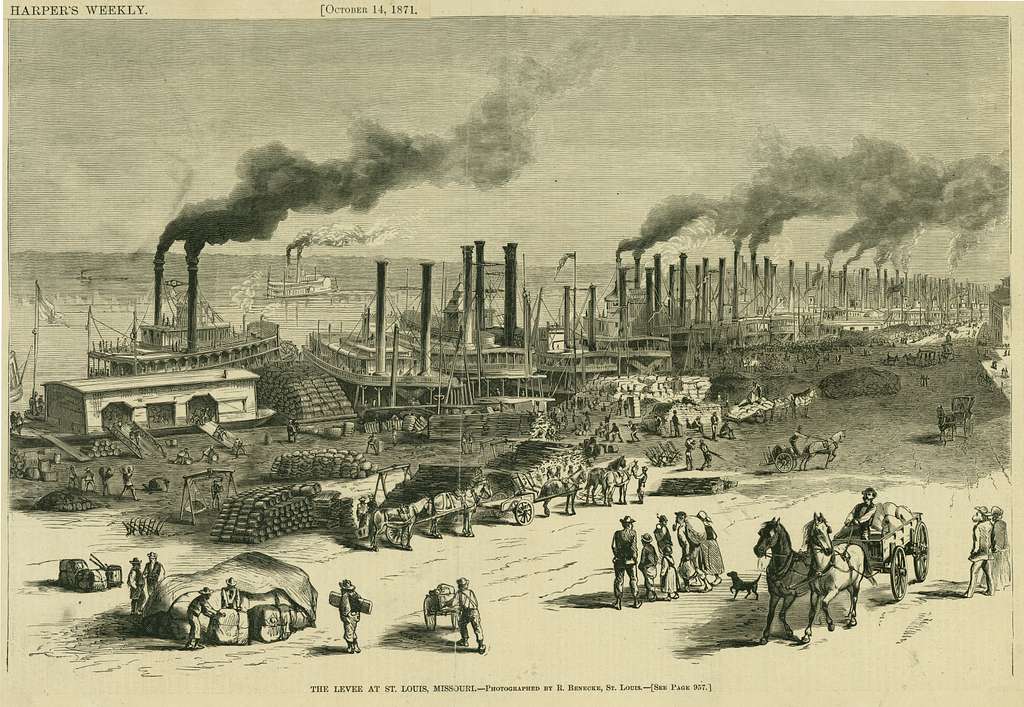

Life and Commerce on the Mighty Missouri

In the mid-1800s, the Missouri River was the lifeline of the American frontier, a bustling thoroughfare for commerce and migration (via New World Encyclopedia). Steamboats like the Great White Arabia were the workhorses of this era, carrying goods and passengers across the vast expanse of the Midwest.

Source: Devon Schreiner/Pexels

However, navigating the Missouri was perilous, with hundreds of boats succumbing to its unpredictable waters. The river claimed nearly 400 steamboats over its course, speaking to its might and the risks of river commerce.

The First Steamboat On The Missouri River

Though many traveled on the Missouri River throughout American history, the first steamboat didn’t make the voyage until 1819. During this time, four steamboats left St. Louis to try to make it through the mouth of the Yellowstone River.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Of these four, only one made it to Council Bluffs, Nebraska. The Missouri River’s waters were too tough for the boats — a claim that would persist long into the 1800s.

Fort Benton, Montana

Fort Benton, Montana became an important port on the Missouri River, especially once steamboats began to increase trade and travel in the region. However, traveling on the river remained risky, thanks to those rough waters.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Before 1864, only six steamboats had ever arrived at Fort Benton. Only a few years later, between 1866 and 1867, Fort Benton saw about 70 steamboat arrivals.

The Effect Of Steamboats

Steamboats successfully mastering the Missouri River at least occasionally had a monumental effect on the lands and towns attached to the water. Suddenly, everything opened up for people on the frontier in places like Kansas.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

“When the first steamboat entered the Missouri in 1819, it opened a colorful history of wild adventures and hazardous trips, led by a group of pilots who were unsurpassed in river navigation anywhere in steamboat lore,” author Jack Lepley once said.

The Importance Of The Missouri River

The Missouri River has long been an important feature of many states, particularly Kansas and Missouri. Many Native Americans and explorers had use of the Missouri in the centuries before westward expansion.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

However, the Missouri also led to the creation of many major cities still thriving today. For example, Kansas City was created after French fur traders arrived in the area by using the Missouri for travel in the early 1800s.

Ancient Trails Alongside The Missouri

Throughout the American Frontier, various trails such as the Santa Fe and California trails had their starting points at the Missouri River. In this way, the river opened up the west of the country to explorers and settlers.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Settlers also were able to travel throughout Kansas to find new homes by using the river system. Though the Missouri has always been deemed rough, its efficiency when traveling has never been doubted.

The Dangers Of Steamboats

While steamboats became an efficient way to transport both goods and travelers, it wasn’t without its dangers. The rough waters of rivers like the Missouri could often devastate these boats.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Snags from fallen trees hidden in the water could easily sink an entire steamboat. Throughout the 1800s, these snags took down hundreds of steamboats within minutes. It was one of these snags that ultimately decided the Arabia’s fate.

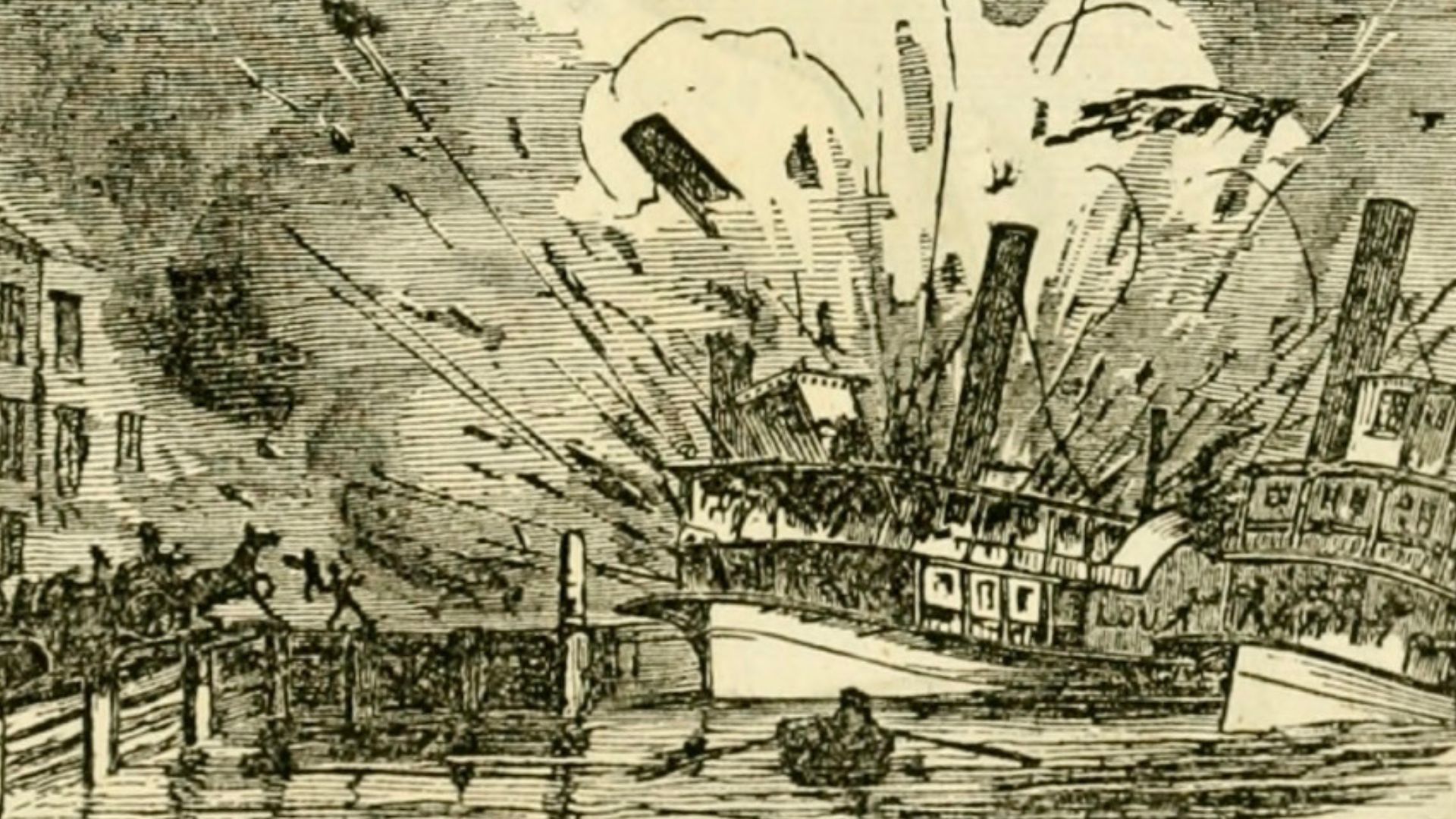

Explosions On Steamboats

Passengers and crewmembers on steamboats didn’t only have to worry about possible snags that would sink the ship. Other dangers, such as explosions on board the ship, could be common during the 1800s.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Back during this time, these steamboats operated at incredibly high pressures. As a result, sudden boiler explosions became commonplace — and deadly.

A Watery Grave Turned Farmland

The reason these steamboat relics are found beneath Kansas farmland today is due to significant human intervention. At the end of the 19th century, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers undertook massive projects to tame the Missouri River’s flow, altering its course and speeding up its current for safer and quicker travel.

Source: Tomasz Sienicki/Wikimedia Commons

This engineering feat inadvertently moved the river away from several of its old channels, leaving the wrecks of steamboats like the Arabia stranded on dry land, waiting to be discovered by future generations.

The Legend of Buried Treasures

For decades, local lore among Kansas City residents hinted at a steamboat laden with goods, buried beneath their land. The story of the Great White Arabia, filled with barrels of Kentucky bourbon, was a tantalizing local legend that many considered just a myth.

Source: N/Unsplash

However, the truth, as revealed by the eventual discovery of the Arabia, was even more fascinating. Instead of bourbon, explorers found Champagne, as well as a time capsule of life in the 1800s, perfectly preserved under the earth (via We Are the Mighty).

Unearthing the Past

In 1987, a dedicated team from Kansas City set out to turn legend into reality. Fueled by stories passed down through generations and armed with historical research and modern technology, they located the Great White Arabia less than a year after beginning their quest (via We Are the Mighty).

Source: The Arabia Steamboat Museum

The excavation was not just a significant archaeological endeavor but a deeply personal journey into the heart of American history, uncovering a slice of the past that had been lost to time and the elements.

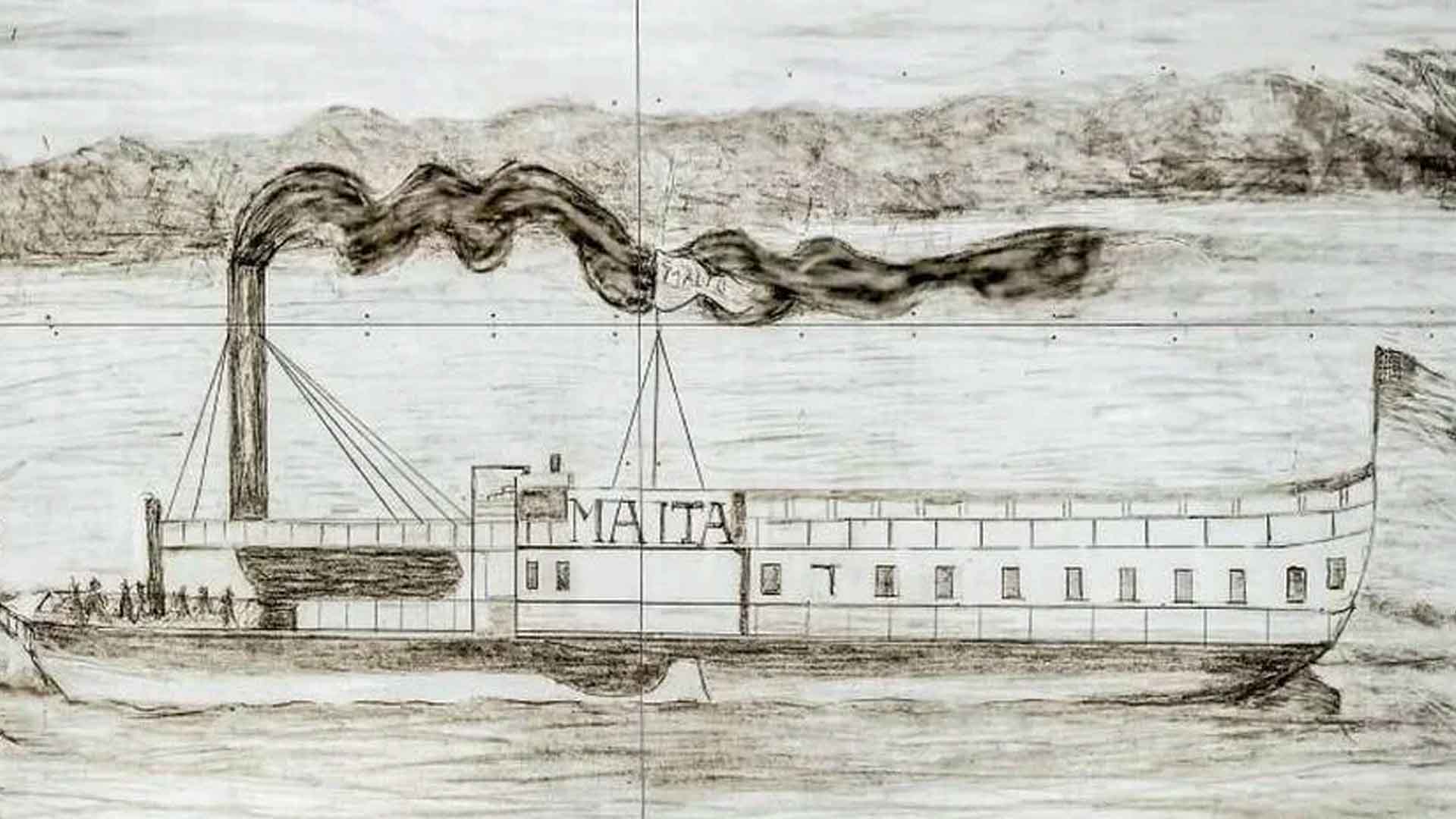

The Malta Joins the Story

Following the discovery of the Great White Arabia, another steamboat, the Malta, was found buried under Kansas soil (via The Arabia Steamboat Musem). Like the Arabia, the Malta was a vessel of commerce, swallowed by the river’s depths, only to be revealed years later, far from the water.

Source: The Arabia Steamboat Museum

These discoveries underline the volatile nature of 19th-century river travel and the changing course of the Missouri River, which left these once-mighty vessels to rest in an unexpected grave.

A Preservation Like No Other

The preservation conditions beneath the Kansas fields were nothing short of miraculous. The cargo of the Great White Arabia, buried under layers of silt and cut off from light and oxygen, remained remarkably intact.

Source: The Arabia Steamboat Museum

This unprecedented state of preservation has provided historians and archaeologists with an invaluable snapshot of daily life and commerce in the 1800s, offering insights into the material culture of the American frontier that would have otherwise been lost.

From Cornfields to the Classroom

The discoveries of the Arabia and Malta extend beyond mere historical curiosity; they serve as educational treasures, providing a tangible link to the past.

Source: Public Domain/Missouri History Museum

The stories of these ships and their cargo offer a vivid illustration of the dangers and dynamics of 19th-century American life, bringing history to life in a way that textbooks alone cannot match.

Treasures Unveiled

Among the Arabia’s unearthed treasures were personal items, tools, and goods meant for frontier stores. Each artifact tells a story, from the elaborate china meant for a family’s new start in the West, to the simple toys that would have delighted children of the era.

Source: Michael Barera/Wikipedia

These relics are echoes of the hopes, dreams, and daily realities of those who sought a new life in the expansive American frontier.

The People On The Arabia

The Arabia’s cargo that was discovered also gives some more historical detail into the lives of those who traveled on the steamboat. For example, many Mormon settlers were on the boat at the time of the sinking, making their way to a new life in Utah.

Source: Michael Barera/Wikimedia Commons

But they weren’t alone. Some soldiers also made up the passenger list, as they were heading to forts in Montana.

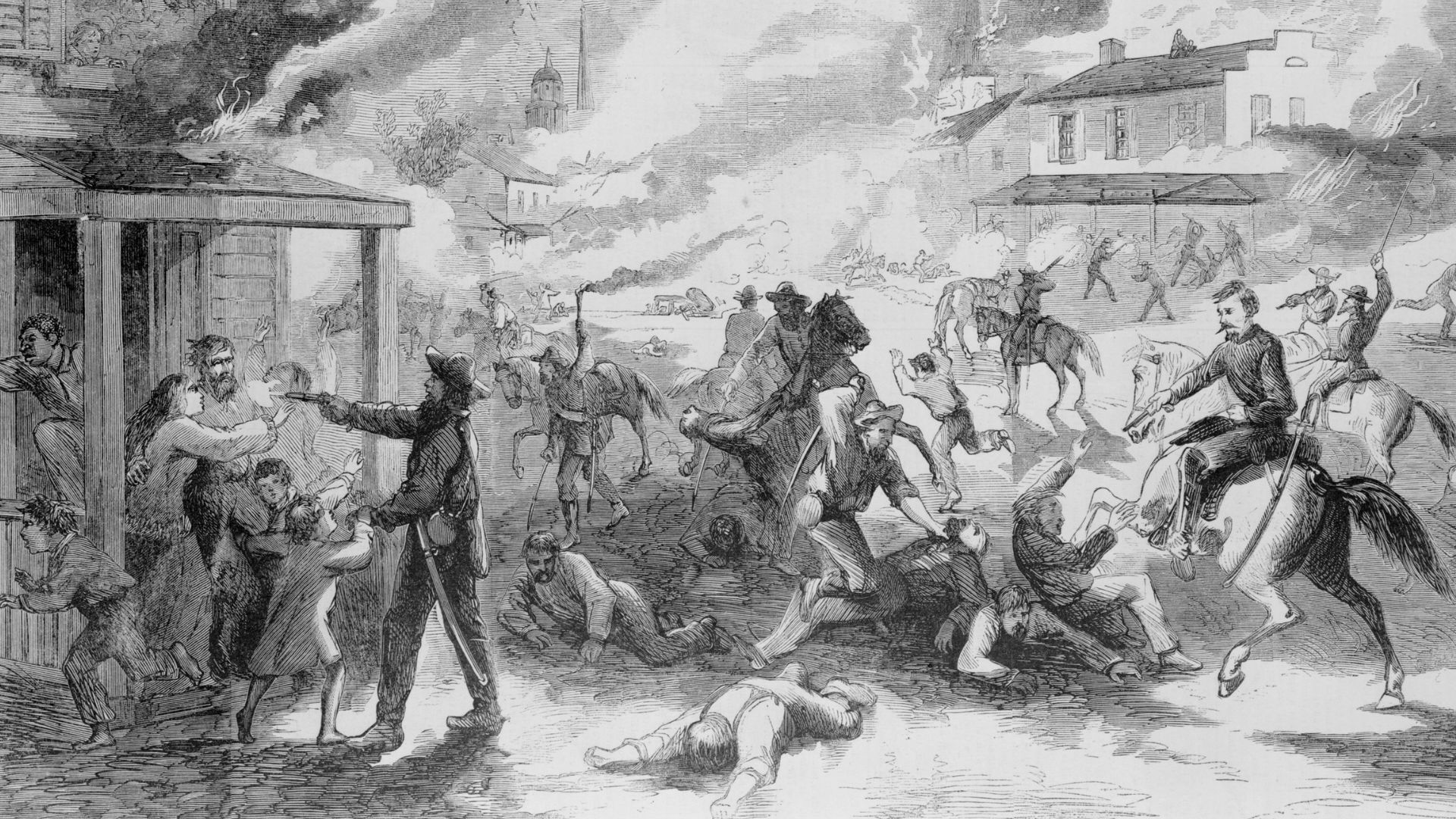

A Steamboat In The Middle Of Bleeding Kansas

The Bleeding Kansas War — also known as the Border War — was occurring during the time of the Arabia’s travels. This war would last from about 1854 to 1859.

Source: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, the Arabia also has connections to the war. At one point, pro-slavery men found rifles on the steamboat that were headed toward abolitionists. This discovery almost caused the passengers who brought the crates on board to be lynched.

The Arabia Steamboat Museum: A Time Capsule

Today, the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City stands as a nod to the enduring spirit of discovery and preservation.

Source: The Arabia Steamboat Museum

Housing the largest single collection of pre-Civil War artifacts in the world, the museum offers visitors a unique glimpse into the past, showcasing items ranging from fine china to the oldest preserved pickles.

Continuing the Journey

The story of the steamboats buried beneath Kansas is far from over. The ongoing preservation efforts and research into the artifacts found on the Arabia and Malta continue to shed light on this fascinating chapter of American history.

Source: The Arabia Steamboat Museum

As the Arabia Steamboat Museum continues to add new exhibits and share its findings, the legacy of these 19th-century vessels lives on, offering new generations a window into the past and inspiring curiosity and wonder about the countless stories still hidden beneath our feet.