These Dinosaurs Broke a 150-Year-Old Scientific Rule

A long-standing scientific rule considered a fundamental truth has been unexpectedly and intriguingly challenged after examining fossilized dinosaur remains from America’s coldest northern territories.

Researchers from the UK and Alaska recently published a study that questions a 150-year-old principle that suggests an animal’s body size is directly affected by the temperature of the region it lives in.

Bergmann's Rule

During the middle of the 19th century, German biologist Carl Bergmann introduced an idea that suggests animals in colder climates can expect to have a greater mass than their counterparts in warmer regions of the world.

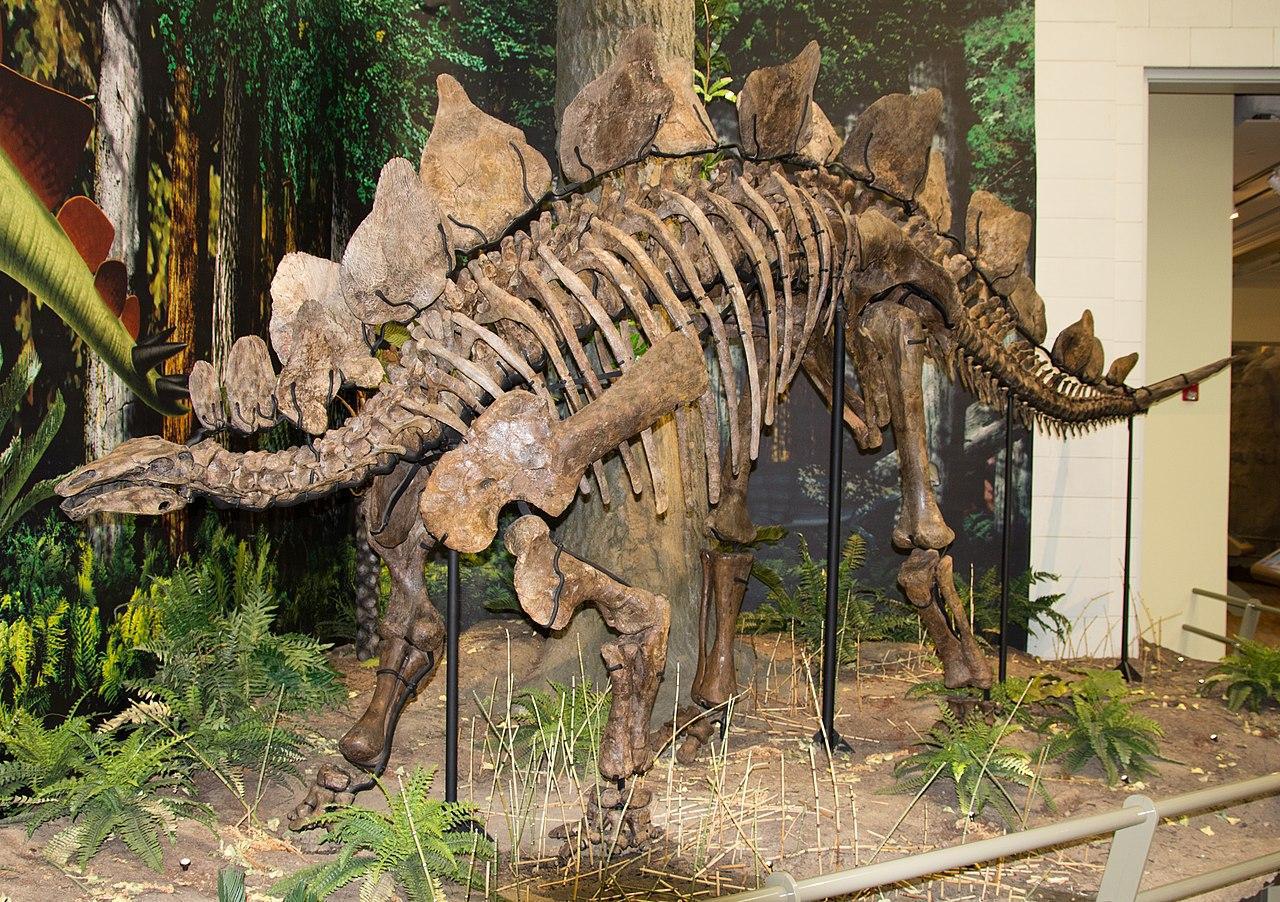

Source: Wikimedia

One such example is a polar bear, which can generally weigh up to three times more than a black bear. This observation would become known as Bergmann’s Rule and has been considered a scientific principal since 1847.

Researchers Believe They Have Broken Bergmann's Rule

For the past 150 years, Bergmann’s Rule has remained somewhat of a biological consonant that numerous species, including humans, abide by.

Source: Freepik

However, according to Newsweek, a team of researchers from the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, working with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, believe they have discovered evidence to contradict this rule.

Dinosaurs Don’t Play By the Rules

Lauren Wilson, a UAF graduate student and the study’s lead author, explained in a statement that dinosaurs’ diverse body sizes appear to bypass this rule.

Source: Wikimedia

“Our study shows that the evolution of diverse body sizes in dinosaurs and mammals cannot be reduced to simply being a function of latitude or temperature,” she said.

New Study Produces Evidence to Support Claim

The team of researchers led by Wilson published a new study in the journal Nature Communications, which provides evidence to support their claim.

Source: Wikimedia

First, Wilson and her colleagues reviewed an extensive amount of fossil records to determine whether Bergmann’s Rule can be applied to prehistoric animals such as dinosaurs. To their surprise, the answer appeared to be no in some cases.

Bergmann's Rule Only Applies to Certain Animals

According to the data produced by Wilson and her team, Bergmann’s rule only applies to a small selection of animals.

Source: Wikimedia

“We found that Bergmann’s rule is only applicable to a subset of homeothermic animals (those that maintain stable body temperatures), and only when you consider temperature, ignoring all other climatic variables,” she said.

Data Collected By Researchers

The study explains that the researchers meticulously sifted through the fossil records of America’s most northern dinosaurs, including many discovered in Alaska’s Prince Creek Formation.

Source: Wikimedia

Yet, despite giving Bergmann’s rule the benefit of the doubt, they discovered no credible evidence suggesting the animals living in these freezing temperatures had increased body mass compared to relatives in more temperate regions.

Researchers Believe the Rule is an Exception

After going through all of their data, the researchers believed they had sourced enough evidence to say with certainty that Bergmann’s rule was more of an exception.

Source: Wikimedia

“This suggests that Bergmann’s ‘rule’ is really the exception rather than the rule,” she said.

The Credibility of Ecological Rules

Speaking on the discovery, Jacob Gardner, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Reading and the other lead author of the paper explained fossil records can play a significant role in determining the credibility of ecological rules.

Source: Wikimedia

“The fossil record provides a window into completely different ecosystems and climate conditions, allowing us to assess the applicability of these ecological rules in a whole new way,” he said.

Understanding the Past Through Ancient Fossils

Patrick Druckenmiller, director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North and another of the study’s co-authors, shared his thoughts on the data, suggesting ancient fossils help biological researchers better understand the complex evolution of animals.

Source: Wikimedia

“You can’t understand modern ecosystems if you ignore their evolutionary roots. You have to look to the past to understand how things became what they are today,” he said.

Testing Modern Scientific Hypothesis

The findings published in the new study showcase how important the fossil record is and why it should be used by biologists and any scientist who hopes to test modern scientific rules and hypotheses.

Source: Freepik

A similar analysis was carried out on several modern mammals and birds, and the researchers obtained results that were the same to a certain extent.

The Importance of Revision

While many researchers are often engaged in a quest to discover a new discovery, the recent study centered on Bergmann’s rule highlights the importance of revision from time to time.

Source: Wikimedia

Going forward, the researchers hope to conduct further investigations and examine several other species of animals to discern which follows Bergmann’s rule. This will allow them to ascertain if any environmental factors contributed to the original observation.