Underwater Labyrinth Hidden Beneath Mexico Contains a Huge Swathe of Life

Researchers working deep within the dark underworld of a carbonate aquifer in Mexico’s Yucatán region have discovered an abundance of microbial life.

Breaking new ground, scientists have embarked on a journey into the uncharted passageways of these cave systems, spanning a staggering 1,000 miles. Their pioneering efforts have led to the discovery of vibrant colonies of microbial organisms nestled within the layers of freshwater.

The Yucatán’s Carbonate Aquifer

Deep beneath Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula lies a unique carbonate aquifer. Researchers have been slowly mapping the labyrinth, which turns out to be one of the most extensive groundwater systems ever discovered.

Source: Wikimedia

Under the water in this part of Mexico lies a complex network of tunnels, enormous caves, and various sinkholes, some of which are toxic. However, the labyrinth also provides a valuable source of drinking water for the millions of tourists and locals in the region.

A Vast Wealth of Microbial Life

Matthew Selensky, who worked on the research conducted at the aquifer while at Northwestern University, shared his thoughts on the recent samples, which provided researchers with evidence of a vast wealth of microbial life.

Source: Wikimedia

“These are incredibly special samples of underground rivers that are particularly difficult to obtain,” said Selensky.

Life in an Aquifer

Microbial life exists in the layers of freshwater that sit atop the saltwater drawn in from the Gulf of Mexico. The metropolises of life must contend with several consequences of living in such an environment.

Source: Wikimedia

According to researchers, in the salty environment, microbial life fights against acidity, light, varying temperatures, and assorted concentrations of nutrients.

Collecting the Samples

An experienced team of cave divers from the local Under The Jungle dive center collected over 75 samples. Geobiologist Magdalena Osburn and her team at Northwestern University later tested these samples.

Source: Freepik

The researchers were able to sequence genes, which allowed them to identify various microbe species. According to their results, an astonishing 4,183 unique sequences, representing 917 different families of microbes, were discovered.

Microbes Play Key Role in Ecosystem

Lead researcher Osburn states, “The microbial communities form distinct niches.”

Source: Wikimedia

She continued, “There is a varying cast of characters that seem to move around, depending on where you look. But when you look across the whole data set, there’s a core set of organisms that seem to be performing key roles in each ecosystem.”

Comamonadaceae: What Are They?

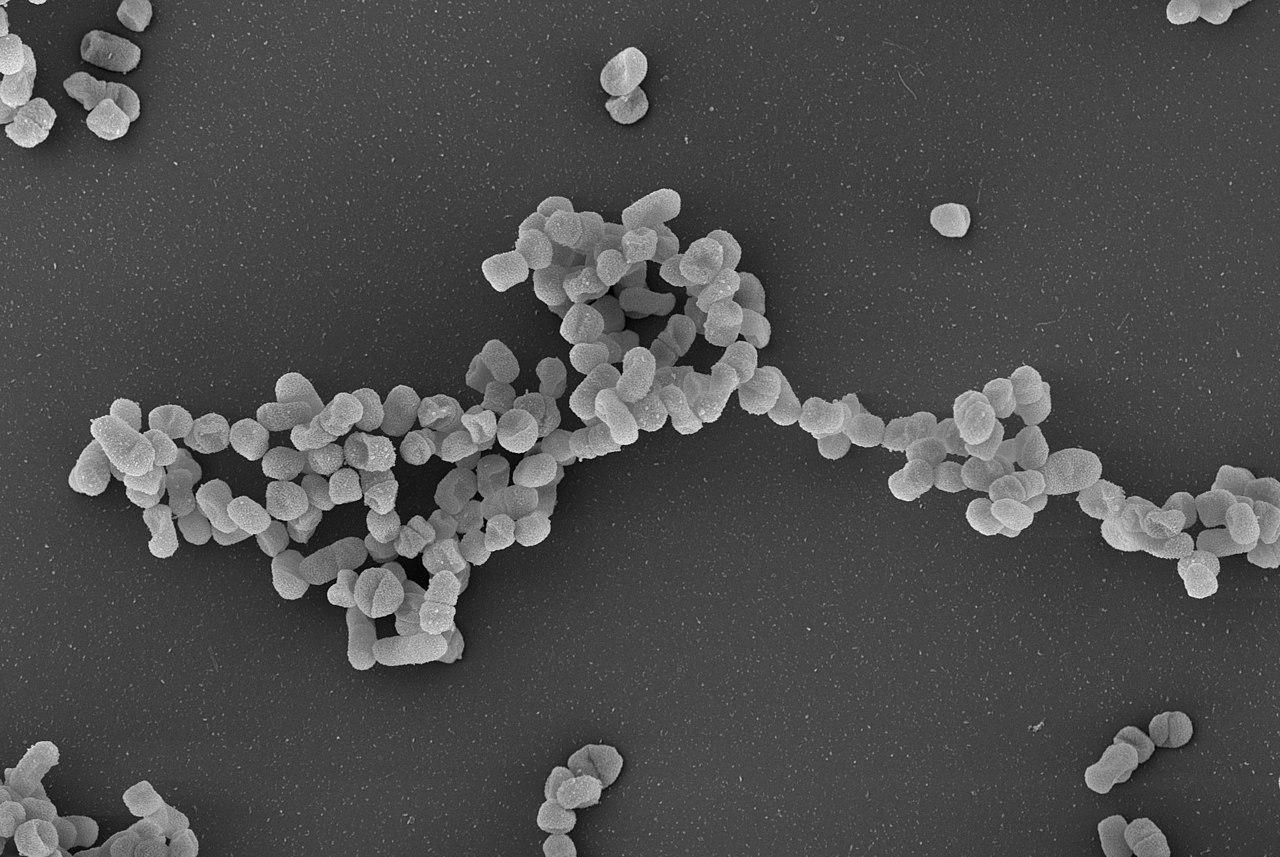

The research team sourced samples from 12 sites, and one family of bacteria, the Comamonadaceae, was present in all of them.

Source: Wikimedia

Under a microscope, the Comamonadaceae are tiny, rod-shaped organisms that can also be found in various other environments, including soil and bodies of water. Oxygen is essential to their survival, and they are able to move using their tail-like flagella.

Comamonadaceae’s Duty in the Aquifer

The Comamonadaceae bacteria have been observed taking on different roles in various regions of Mexico’s carbonate aquifer. Researchers have noticed, however, that it always plays a significant role in the ecosystem.

Source: Wikimedia

“It seems that Comamonadaceae performs slightly different roles in different parts of the aquifer, but it’s always performing a major role,” explains Osburn.

Bacteria Working Together in the Water

Comamonadaceae has been observed working with other forms of bacteria in the water, such as the nitrogen-eating bacteria Gemmataceae and various species, like Methyloparacoccus.

Source: Wikimedia

“Depending on the region, it has a different partner. Comamonadaceae and its partners probably have some mutualistic metabolism, maybe sharing food,” said Osburn.

Potential to Be Felt By Humans

The Methyloparacoccus will indulge in the methane and even some of the organic-eating microbes. Many of these bacteria likely play a significant role in the water chemistry observed in various regions of the aquifer.

Source: Freepik

“This underground river system provides drinking water for millions of people,” notes Osburn. “So, whatever happens with the microbial communities there has the potential to be felt by humans.”

Pollutants Begin to Seep Into the Aquifer

As the aquifer is relatively isolated, its ecosystem has remained somewhat untouched compared to several over-exposed environments above.

Source: Wikimedia

However, researchers have begun to notice that a small number of pollutants, such as pesticides, fertilizers, drugs, and personal care products, are beginning to enter the complex system. Should the water source become continuously polluted, this may become a major problem in the future.

Aquifer May Become Vulnerable to Humans

Researchers recently discovered that 13 out of a potential 173 sinkholes were free of pollutants.

Source: Wikimedia

This suggests that even an aquifer as isolated as this cannot escape the consequences of human activity. Scientists hope further research conducted in the region will give them a better understanding of microbial life’s role in the ecosystem and allow them to better understand humans’ effect on the region.